5. Stanley Spaeth, Imperial Cult in Roman Corinth: A Response to Karl Galinsky’s ‘The Cult of the Roman Emperor: Uniter or Divider? in Rome and Religion: A Cross- Disciplinary Dialogue on the Imperial Cult. WGRWSS. Edited by J. Brodd and J. Reed (Atlanta: Society of Biblical Literature, 2011), 63.

6. Benjamin W. Millis, Social and Ethnic Origins of the Colonists in Early Roman Corinth in Corinth in Context: Comparative Studies on Religion and Society (Leiden: Brill, 2010), 31.

7. Robert M. Grant. Paul in the Roman World: The Conflict at Corinth (Louisville: Westminster John Knox Press, 2001), 14. “Al igual que Cartago, Corinto fue una colonia romana establecida por Julio César poco antes de su asesinato en 44 a.C. Tanto Corinto como Cartago se erigían sobre las ruinas de las ciudades devastadas por los ejércitos romanos en el año 146 a.C. Fueron casi fundamento único y sirvieron para avanzar los intereses comerciales de Roma y sus desempleados pobres”. Warren Carter, The Roman Empire and the New Testament: An Essential Guide (Nashville: Abingdon Press, 2006), 56. James S. Jeffers, The Greco-Roman World of the New Testament Era: Exploring the Background of Early Christianity (Downers Grove: InterVarsity Press, 1999), 84. John Fotopoulos. Food Offered to Idols in Roman Corinth: A Social-Rhetorical Reconsideration of 1 Corinthians 8:11:1 . WUNT (Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck, 2003), 158.

8. Victor Paul Furnish, Corinth in Paul’s Time: What Can Archaeology Tell Us? Biblical Archaeology Review Vol. XV (1988): 15.

9. John C. Hurd, The Origin of 1 Corinthians (Macon: Mercer University Press, 1983), 47. “Por lo tanto, 1 Corintios da evidencia de dos acontecimientos que precedieron a su composición: a) una triple llegada de noticias de Corinto y b) una carta anterior de Pablo a los Corintios”.

10. John K. Chow, Patronage and Power: A Study of Social Networks in Corinth (Sheffield Academic Press, 1992), 11.

11. Victor Paul Furnish, The Theology of the First Letter to the Corinthians (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1999), 12. See also Gerd Theissen, The Social Setting of Pauline Christianity (Philadelphia: Fortress Press, 1982). 56.

12. Theissen, The Social Setting , 123.

13. Grant, Paul in the Roman, 13.

14. Carter, The Roman Empire, 56.

15. Petronius, Sat. 29; CIL. 11. 741.

16. Ronald F. Hock, The Social Context of Paul’s Ministry: Tentmaking and Apostleship (Philadelphia: Fortress Press, 1980), 37ss.

17. David G. Horrell, The Social Ethos of the Corinthian Correspondence: Interest and Ideology from 1 Corinthians to 1 Clement. SNTW (Edinburgh: T & T Clark, 1996), 64.-73.

18. Michael D. Goulder, Paul and the Competing Mission in Corinth (Peabody: Hendrickson Publishers, 2001), 268-70. Ver también David G. Horrell, An Introduction to the Study of Paul (London: T & T Clark, 2006), 106-112. Señala que “hasta hace poco, el tema de la relación de Pablo con el Imperio romano fue algo descuidado, especialmente en comparación con el tema dominante (e importante) de la relación de Pablo con el judaísmo”. Ver también John K. Chow, Patronage and Power , 12-14.

19. E. A. Judge, Social Distinctive of the Christians in the First Century. Ed. David Scholer. (Peabody: Hendrickson Publishers, 2008), 117-135.

20. Roger, W. Gehring, House Church and Mission: The Importance of Household Structures in Early Christianity (Peabody: Hendrickson Publishes, 2004), 135.

21. Wendell Lee Willis, Idol Meat in Corinth: The Pauline Argument in 1 Corinthians 8 and 10 (Chico: Scholars Press, 1985), 104.

22. Charles B. Puskas and Mark Reasoner, The Letters of Paul: An Introduction (Collegeville: Liturgical Press, 2013), 89-90.

23. Strabo, Geography 8.6.20-23.

24. Theissen, The Social Setting , 15.

25. David E. Garland, 1 Corinthians, Baker Exegetical Commentary on the New Testament (Grand Rapids: Baker Academic, 2003), 365. “Sacrificio era la forma acostumbrada de, tanto la adoración pública como privada en el mundo antiguo”. Ver también Dennis E. Smith, From Symposium to Eucharist: The Banquet in the Early Christian World (Minneapolis: Fortress Press, 2003), 173-217.

26. W. A. Meeks, The First Urban Christians: The Social World of the Apostle Paul (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1983), 27.

27. Chow. Patronage and Power, 38ss. Ver también A. D. Clarke, Secular and Christian Leadership in Corinth: A Socio-historical and Exegetical Study of 1 Corinthians 1-6 (Leiden: Brill, 1993). 5-15. Joshua Rice, Paul and Patronage: The Dynamics of Power in 1 Corinthians (Eugene: Pickwick Publications, 2013), 91-156.

28. Jerome Murphy-O’Connor, Keys to First Corinthians: Revisiting the Major Issues (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2009), 184-185.

29. A. C. Mitchell. Rich and Poor in the Courts of Corinth: Litigiousness and Status in 1 Cor. 6:1-11 . New Testament Studies, 39 (1993): 562-86.

30. Justin Meggitt, Meat Consumption and Social Conflict in Corinth . Journal of Theological Studies 45 (1994): 137-141.

31. Udo Schnelle, Apostle Paul: His Life and Theology. Translated by M. Eugene Boring (Grand Rapids: Baker Academic, 2005), 356. “Los romanos empiezan a percibir a los cristianos como un grupo que adora a un criminal ejecutado como un dios y que proclama el fin inminente del mundo. La persecución neriana que se produjo solo ocho años después de escribir Romanos, muestra que debe haber habido tensiones crecientes entre los cristianos por un lado y las autoridades y la población de Roma por el otro”.

Capítulo I

LA CORINTO ROMANA: UNA PERSPECTIVA GENERAL

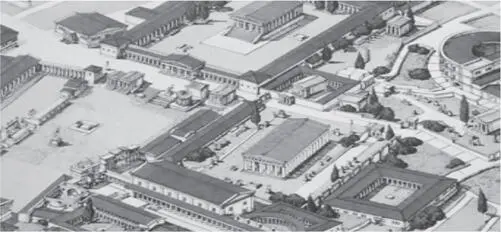

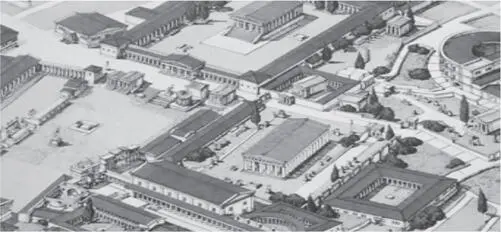

Grabado 1. Corinto romana, su arquitectura y administración.

Introducción

Hay ahora un supuesto bien concreto entre los estudios del Nuevo Testamento de que el apóstol Pablo escribió la primera epístola a los Corintios y que esta fue escrita en Éfeso. 1Los eruditos están casi unánimes en que el progreso importante de Pablo tuvo lugar al comienzo de su ministerio 2y que las epístolas corresponden a la última parte de su carrera. Además, que fue impresionado para escribir 1 Corintios en respuesta a las noticias alarmantes de la iglesia. 3No hay indicación de que fuera expulsado de Atenas por una turba (de agitadores judíos) o por las autoridades. Sencillamente, dejó la ciudad y se fue a Corinto, que era la capital de la provincia romana de Grecia, conocida como Acaya. 4Había judíos en Corinto (como Aquila y Priscila) que fueron expulsados de Roma. Vale la pena señalar que los judíos en Roma se distribuyeron entre algunas sinagogas de distrito, en lugar de reunirse en una misma comunidad. La más antigua y, casi seguramente la más grande de las congregaciones, estaba en la zona llamada transtiberiana, en el oeste del Tíber. 5

Los judíos, mayormente, mantuvieron sus antiguas tradiciones e instituciones en la Diáspora y algunos fueron lentos para integrarse a la forma de vida secular grecorromana. 6Hay un desacuerdo acerca de la fecha de expulsión de los judíos de Roma y el arribo de Pablo a Corinto, según Hechos 18:2. El relato en la cita anterior dice que Claudio expulsó a todos los judíos de Roma; esto es difícil aceptarlo. El relato de su visita inicial a Corinto en Hechos 18, ofrece algunas evidencias históricas; 7sin embargo, algunos intérpretes vinculan la expulsión con el esfuerzo del emperador de pacificar la comunidad judía durante el primer año de su reinado. 8

Читать дальше