Now it’s raining outside and it makes me think of everything that happened because of my hands and these stupid cunt fingers. I could blame them for everything, no? Because if I didn’t have fingers or hands maybe none of this would’ve ever happened.

Papi would come home from work with black stains on his shirt. I remember him washing his hands at the kitchen sink, scrubbing his knuckles in front of the window. He stopped doing it after awhile and I got used to his hands looking like he’d been working under the hood of a car.

He came home one day wearing a smile that looked like he’d been given an award. He’d been given a promotion as Managing Director of Inventory Planning, which sounded a lot better than steelworker. Mom told us later, when she was tucking us in, that he was going to be assigned to the second floor with a window in his office. The next morning we were going shopping to buy him a suit and a briefcase.

There was one time before then when Papi was watching TV and Mom and Estrella had gone to the supermarket. It was just the two of us and I asked him what he would’ve wanted to be if he would’ve gone to school. He said he wanted to be a painter. Not of houses, but an artist. In the garage, there was a painting of his of a waterfall between two mountains and two deer. When we’d clean the garage or take down Christmas decorations from the attic, I’d stare at it. And I never could believe Papi had painted it because it looked so professional.

He was in the dressing room at Mervyns trying on a navy blue suit for his new promotion and it was like he’d stepped out of a movie. “Where’s the sombrero?” I asked. I wanted him to sing. I wanted him to do a two-step. I extended my arms and said, “¡Ay! Te ves muy caballero.” Estrella brought him ties of different colors and told him how smart he looked. He’d put them on as he wiggled his toes under his socks, then stood in front of the mirror wearing his silly smile. Our faces would peek out from the sides of his back checking to see what a Managing Director looked like.

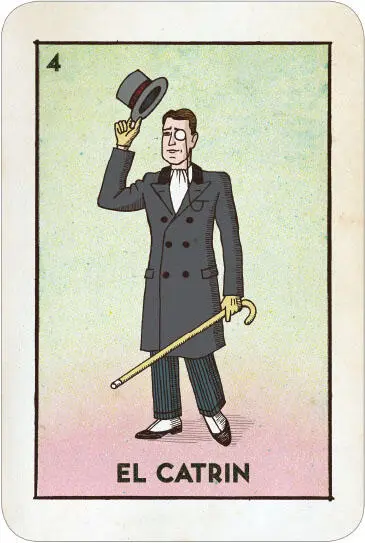

We didn’t mention anything about the promotion to the Silvas that weekend. We went to misa , ate lunch, played Lotería , then drove home. Papi kept grabbing a section of the newspaper that night even though he’d already looked through it. He’d walk to the garage and come back again. Before I went to bed I gave him a hug.

“¿Qué?” he said. “You never do that.”

When I got home from school the following day, Mom called.

“He didn’t get it,” she said. Just like that. Like if he’d forgotten to pick up cereal on his way home.

“What?”

“He didn’t get it, Luz.”

She was on the other side of the interstate helping someone put together a piñata for a posada . She wasn’t getting home until later and said it didn’t work out because they changed their minds. Maybe it was his English. She didn’t know. “Just be nice. Don’t say anything. Act normal.” I hung up knowing that at any minute he’d walk through the door, and I didn’t know what to do. I thought of going to Tencha’s to help her with the tamales she had to make, but I went to my room instead. When he came home I pretended to be asleep.

That weekend when we played Lotería with the Silvas, Papi did something he’d never done before. When you call the cards you sing the riddles. That’s what makes it different from bingo. It’s not as easy as calling out numbers because in Lotería you have to figure out el dicho to figure out the image. Either that or keep your eyes on the cards being thrown by the dealer. But the faster the riddles, the faster the game.

Papi got up and dealt the cards. At first his voice was off-key, and you could tell he was nervous. But he got stronger the more we played.

¡Don Ferruco en la alameda, su bastón quería tirar!

— (El Catrin)

¡Para el sol y para el agua! — (El Paraguas)

¡El que con la cola pica, le dan una paliza! — (El Alacrán)

Los dichos . Everyone knows them from church fairs and parties. But there’s some that people make up for fun. Like La Sirena . Tío Fernando would whistle when she was called because she’s topless, and Pancho Silva, who normally dealt the cards, would say, “¡La encuerada para el Tío Fernando!” And for El Venado , he’d sing, “¡Lo que el Tío José mata cada fin de semana!” Because Papi liked to go hunting.

But the day Papi dealt, I hadn’t known he knew the riddles because I’d never heard him deal, just like I’d never known he wanted to be a painter.

He started singing los dichos and they sounded like songs he’d learned from when he was a boy. I couldn’t keep up with the game because he was singing so fast, so loud. Pancho kept bringing him beers, making him louder. And when I saw him next to Papi I thought, he’s no movie star. He’s no Pedro Infante. But look at Papi! He’s handsome. He’s good-looking. With his chin up and his voice loud. He’s a movie star. I sat there and looked at him and I didn’t even try to play the game, because I couldn’t. I couldn’t keep up. So I started to clap, in my head, softly at first, then louder and louder until someone called out: ¡Lotería!

You could say I looked Indian and she looked gringa . At school the teachers would ask Estrella if she was Spanish, like from Spain, because of her eyes. “Are they hazel?” Every time I caught her telling teachers she was Spanish I’d walk up to her in the hallway, between classes, with my finger in her face and say, “¡Hey! ¡Te llamas Castillo!” But real Mexican and in front of everyone.

Estrella lived in Reynosa for two years after she was born, before moving to the States. Then I arrived, the natural-born out of all of us, which is weird because I’m the one who looks more Mexican.

We used to visit Buelo Fermín and Tío Carlos in Reynosa during the summer, but there we had to speak in Spanish. The only place I could speak comfortably was in my head. We’d sit with Buelo Fermín in his kitchen and nod our heads, and when Estrella would say something I’d wait for her to trip over a sentence. She never spoke Spanish at home so I thought she’d make mistakes. But she spoke like everyone else, smooth and easy.

I understood everyone but was too shy to say anything because I didn’t want to sound stupid. I’d lose my words if I spoke. When Buelo Fermín asked me a question, I’d answer him in English. Then he’d throw his shoulders back. He’d point to me and say with his eyes half shut, “No te olvides de dónde vienes.”

Like if I would forget.

But still, I wouldn’t speak to him in Spanish. And so in Reynosa, I was the one who never opened her mouth. If Buelo Fermín spoke to me in Spanish, I’d speak to him in English. It seemed fair. I never paid attention to him anyway. Most of the time I looked at his bruised toes sticking out of his chanclas .

The girls we played with in Reynosa were our age. They liked to run to the market down the block and come back with fruit smothered in lime juice and cayenne pepper. And when I saw them I joined them. Sometimes we’d spray each other with a hose from someone’s backyard or sit on the sidewalk and draw shapes on the pavement with chalk. We’d make sounds between us that didn’t even make sense: ¡Aye! ¡Onda! ¡Bofos! And if they wanted to play chase, I’d run after them. If they wanted to play cards, I’d deal. If they wanted to kick a ball, I’d kick it so far they’d disappear around the block before finding it.

Читать дальше