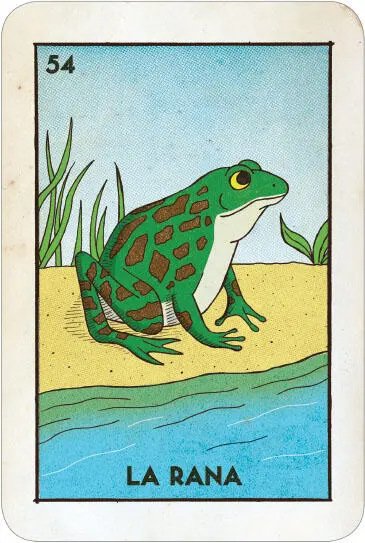

And who comes last, La Rana , the one who reminds me of the sounds we heard from the window when we were trying to fall asleep.

When we were little, when we were kids, we liked to sleep in Buelita Fe’s room whenever we got tired. We fell asleep with the television on in the living room while Papi and them were watching Siempre en Domingo . The wasps hit against the screen and the light outside turned lavender.

Buelita Fe had two beds. Hers was slanted because she had to keep her head above her feet, otherwise she’d snore and wake herself up. Luisa slept on that bed with me, and Gastón and Miriam slept on the other bed with Estrella.

We had never played the game before and I don’t remember who mentioned it. I think it was Luisa. All I can remember was her on top of me pushing her hips into mine like in the movies. That’s what it was, we were just acting like the adults in the movies. Her head tilted side-to-side like she was looking at puppies in a store window. Her tongue was out, and she kept asking, “Wanna make out?” “No,” I said. “You’re gross.” “It’s not gross if the actors do it,” she said. Then she’d get off me and tell me it was my turn, see if I could do any better. I looked over to Estrella and Gastón, and they were just looking. Gastón was lying on his stomach. He turned away like if I were going to flash him or something. But then he would turn around and keep looking. “Don’t act like you don’t want to do it too,” Luisa said. She opened her legs and squeezed me between her. And then I did it, because, so, we were just playing. We had our clothes on. But I was worried Papi was going to hear us from the living room and catch us. He was right there and the door was wide open. But the lights were out in the room, and we were in the dark.

I whispered, “Like that?” She said, “Yeah, like that. But do it harder like the men on TV.” So I did. But then the bed creaked and Estrella started giggling and Luisa said, “Shhh!”

“¿Qué hacen?” Pancho said. He was still alive then.

All of a sudden it was like if some light had been turned on. And we stopped moving. That’s when I noticed how bad Luisa’s breath was.

I didn’t want the bed to creak again so I just relaxed over her. I felt like I was flattening her. But she didn’t tell me to get off, and we fell asleep that way.

Croooc, crooooc!

“What’s that?” I whispered. Gastón heard me and said, “It’s a toad, stupid.” “No it’s not. Toads live in ponds, stupid.” “No, you’re stupid.” “It’s a frog.” “Then why did you ask?” “Because I was asking where it came from, not what it was.” “Well, that’s what you asked.” “Shut up and go to sleep,” I said. And he did, and so did Estrella, and Luisa, and me. We went asleep to the sounds outside, then waited for the sounds to wake us.

My deepest gratitude to the Riggio Program at The New School, the Iowa Arts Fellowship at the Iowa Writers’ Workshop, and the scholarship committee at the Bread Loaf Writers’ Conference. Without your support and encouragement this book would not exist.

My love and thanks to:

All of my professors who have shaped and nurtured me: Andrew Sean Greer, Julie Orringer, Charles Baxter, Kevin Brockmeier, Marilynne Robinson, Zia Jaffrey, Sigrid Nuñez, Sharon Mesmer, Helena Maria Viramontes, Josh Weil, and especially Lan Samanatha Chang and Rene Steinke, who worked specifically on this project.

My peers who read with such generous and thoughtful minds: Dina Nayeri, Stephen Narain, James Molloy, Carlos QueirÓs, Devika Rege, Chanda Grubbs, Greg Brown, Christa Fraser, Ashley Davidson, Jessica Dwelle, Scott Smith, and Luke Sirinides — thank you so much; I will always remember that workshop and carry it close.

My agent, Chris Parris-Lamb, who has been nothing less than a literary prince and hero throughout this entire process. Also, Andy Kifer, an incredible right-hand man and wonderful reader — thank you.

My editor, Claire Wachtel, who embraced this book, believed in it, and protected it in a way I could only have wished for — thank you.

Jarrod Taylor: this book would not exist without you.

My family and friends, near and far: you know who you are and you have my heart.

And to the absurd and audacious hope of wanting to become a writer — thank you.

Mario Alberto Zambrano was a contemporary ballet dancer for seventeen years, dancing in the Netherlands, Germany, Israel, Spain, and Japan before returning to school to pursue a career in writing. He received a BA from the New School, where he was a Riggio Honors Fellow, and completed his MFA at the Iowa Writers’ Workshop as an Iowa Arts Fellow. He is a recipient of the John C. Schupes Fellowship for Excellence in Fiction. Lotería is his first novel.

www.marioalbertozambrano.com

Visit www.AuthorTracker.com for exclusive information on your favorite HarperCollins authors.