We’d been in the car for about three hours and I started to feel lighter, like if there was wind beneath us. The escort officer stayed far enough behind so that it didn’t feel like we were on a leash.

“You know what’s missing?” I said.

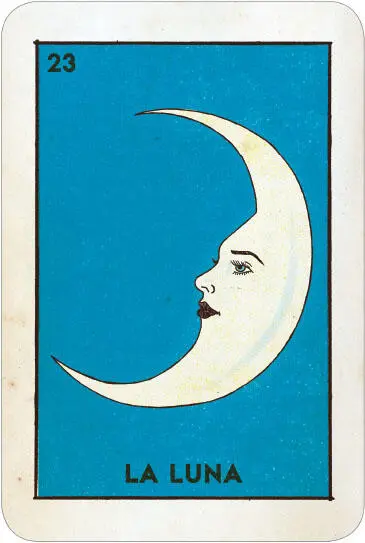

“ ¿Qué? Missing with what?” Tencha said. She was sweating like a glass of cold water. The window was down and the day was all dusty orange. “In Lotería ,” I said. “You know what should be part of the deck?”

“What?”

“An eagle. How do you say eagle in Spanish?”

“Águila.”

“Like Tony Aguilar.”

“Yeah, but without the ‘r.’ ”

“Instead of the first card being El Gallo it should be an American bird, not a Mexican. Because you can’t count on roosters.”

“Mama, what are you talking about?”

“Eagles can fly, Tencha. The only thing gallos do is scream loud and fight.”

We drove farther away from the city and the land became less and less of anything. There were small towns we drove through with posters of Mexican Duvalín outside the stores we passed. But I didn’t see anyone walking on the sidewalks or playing in the parks. It was like they knew we were coming and hid inside to avoid being seen.

“When do the hills start coming?” I asked. “When do we go up and down?”

“Not until after the border,” she said. “When we get to Mexico.”

“I’m not going to have problems, am I? Like you in the States.”

“No, mama. You’re Mexican,” she said. “They’re not going to say anything. You can stay for as long as you want. And you can come back whenever you want. Don’t worry. I have your birth certificate.”

“But I was born here,” I said. And she didn’t say anything.

We stopped at a small convenience store and bought two Cokes and some chicharrones . The lady behind the register spoke to me in Spanish, and I looked at Tencha like if I didn’t understand. “You better start practicing,” she said. “No one’s going to speak to you in English.”

In the car, the road rippled and warped like if it were melting. We had to stop at a checkpoint, a place on the road where cars were waiting for an officer to let them pass. It moved forward every two minutes, so it seemed fine, but I felt sick to my stomach. Tencha turned the radio off so she could concentrate, even though she kept saying it was all going to be simple and fine and there was nothing to worry about. We stopped and I could see the officers open the trunk of a car in front of us. They talked to each other for a long time, then called someone on their walkie-talkie.

I looked out the window and saw something in the desert. At first it looked like a black trash bag blowing between the bushes. But I had to squint because whatever it was, it fell over and got up again, then kicked the dirt. “Look! Can you see that?” I said. Tencha looked out and squinted. “¿Qué?” she mumbled. Before I answered, I squinted again and tried to focus. If it weren’t for when it opened its arms and took two steps, like if he were carrying a crucifix, maybe I wouldn’t have said anything.

“There’s a man out there!”

“I don’t see anything,” she said. “You’re imagining it.”

I looked at her in that way she knew I was serious, but then, when I turned to him, he was gone. “He was there,” I said, pointing. “He must’ve fallen, but he was right there, I saw him.” She rubbed my thigh and said it was the heat. “Take a nap, mama. You’re tired. It’s the sun. Close your eyes.” I kept looking for him but I couldn’t find him. I knew I’d seen him, and so I opened the passenger door and stepped outside.

“Luz! Get in here,” she said, looking forward and back like if someone were coming. But I wanted to see him again, with his arms out to You. How could I not think of Papi at the sight of that man trying to walk? I was running away and trying to forget what had happened, but what if I couldn’t? What if I couldn’t forgive myself? I thought of Papi and how he made me, and how Mom made me, and how their blood is more mine than Tencha’s.

One of the cars in front of us made a U-turn and headed back from where we came from. The escort officer behind us turned his head to see it pass. I looked at the road we’d come from, the way it melted into itself from the heat, then looked at Tencha.

“What, mama?” she said.

I didn’t say anything because I didn’t have to. She knows me. Somos iguales .

“What are you thinking in that little head of yours?” she said, with a face that knew me more than I knew myself. Like if it wasn’t Tencha looking at me, but You.

I turned my head to the officer in front of us searching the trunk of someone’s car. Then to the car driving away behind us.

“What, mama?” she said. “What?”

I knew she might hate me and it’d be a long time before I saw her again. But it was either Mexico or the House of Hope. Maybe I was supposed to run away and open my arms and run through the desert like that man, looking up at You. The way Papi might be doing in his cell, not forgetting but trying to move forward. Trying to forgive himself. And maybe if I ran with my arms out You could take me and decide what to do with me. I looked at Tencha in that way you know us Mexicans know how, in the way You taught us. In that way that says I love you so much it hurts. So when I saw her looking at me like if she were seeing a ghost, I grabbed my backpack from the front seat and ran toward the officer behind us, waving my arms above my head and yelling as loud as I could, “KIKIRIKIKI!! KIKIRIKIKI!! KIKIRIKIKI!!”

And he must’ve thought for sure that I was crazy.

I’m at Casa de Esperanza now, the house where hope lives.

Y me llamo Luz. My sister Estrella , The Star.

I figured I could keep waiting for Papi to get out since that’s all I’ve done. And when I’m done writing the cards, I thought maybe I’d send them to Tencha. That way she can read them and finally accept what happened. Because though I’m Papi’s daughter, I’m honest. That’s what she taught me.

When I think of Estrella I remember how she’d act silly sometimes when she was in a good mood, wet from the pool plopped on the sidewalk, looking like a girl watching television with her head up at the stars. I’d be like her, in the same position, supported by my hands with my butt on the ground, looking up at You. She said behind the face of the Moon, You were there. But she was acting silly and serious at the same time. She wanted to tell me You were right there between us. I looked at her face and saw You, the way she saw You in the Moon. She’d look at me, waiting for me to say something, then start singing “Pena, penita, pena,” and I could almost feel her heart come out of her skin. You and me and her, together in the way she looked at me.

It’s like that sometimes. I see You in people’s faces before they tell me something that means a lot to them. And that’s why I loved her, because I saw You there, in the way she looked at me. Maybe when she was looking at me she was looking at You?

One time, Tencha said to me, “Come here, come here,” like if I were some sort of dog. And I know love is expressed in strange ways, but still. Anyway, there I was, her little dog. She held me tight, and I couldn’t breathe. She said, “Te quiero, Luz. Lo sabes, ¿verdad?”

“Yeah, I know,” I said. And we looked up at the Moon.

Читать дальше