Before we walked out of the building he told us an officer would take us to the hospital and sign us in. We drove to the Medical Center near the zoo off of highway 59, to a huge building that looked like a good place, not some clinic with bums crowding the emergency room. It looked like a place that could fix things. It had forty-four floors and there were doctors with clipboards walking up and down the hallway. When we asked the receptionist for Estrella María Castillo the woman told us she was on the thirty-eighth floor. I remember because I pushed the button in the elevator but it wouldn’t light up, and when the doors opened the hallway was quiet. It seemed like no one was there. But finally a nurse passed. She said I couldn’t go inside the room where Estrella was. All I could do was see her from behind a pane of glass. But all I could see was her chin and the shape of her body past two other beds. I couldn’t see her eyes. There was a curtain blocking half of her face. For all I knew it could’ve been someone else.

When the nurse looked at me she did that tilt of the head like people do, like if I were abandoned. Other nurses started to show up and they looked at me in the same way. Maybe they thought I’d attack them or knock them over or run inside the room no matter what I was told, because they’d heard what had happened. But I didn’t. I stood there and looked at my sister while Tencha walked with them down the hall and asked them questions.

The machines that were next to her beeped louder the longer I stayed, and no matter how much I tried to block them out, I couldn’t. I pressed my palms against the glass and told her how much I love her. How sorry I was. My sister. Just there, sleeping. Not moving. She got blurry from the fog of my breath covering the glass, and I whispered, ¿Y por qué tenías que ser tan tonta? I wrote her name in my mind and imagined the star as I drew it over the glass.

Mom used to say to us, Estrella y Luz, cuánto las quiero .

I pressed my hands harder against the glass and told her it was going to be okay, not because You were going to make it okay but because I was there and You were there and I was really trying to tell You something. Like how much I love You. And if I loved You, wouldn’t that make things better? It didn’t matter if I fell on my knees or threw up my hands and prayed I don’t know how many Hail Marys. Lo siento, Madre María. But it was a matter of Your will. Learn to live with what you lose and that’s what’s meant to be. ¿Verdad? Mom used to say, “Forgive and forget.” I say it to myself over and over when I’m trying to fall asleep at night but it feels like a lie. It turns into a song and then I don’t even know what I’m singing anymore.

Standing there, all of a sudden, I was like a jug of water trying to be taken from one place to another, and little by little, I was spilling. The nurses didn’t even look at me anymore.

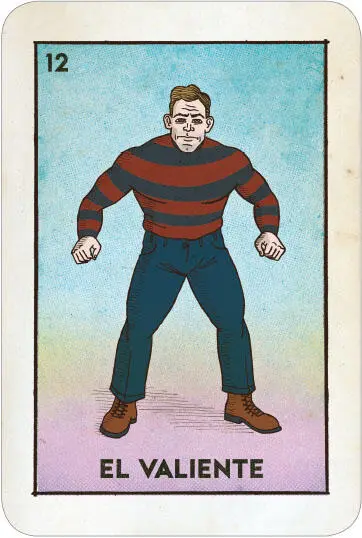

Pancho Silva was fat and never showered. He had gray hair on the sides of his head and a little on top that he combed forward. He told Papi when he first met him that he was going to be a movie star. He was in that Pedro Infante movie Los tres huastecos as a double and was working his way up. He and Pedro Infante were tight, like brothers. But after Pedro’s death in a plane crash Pancho’s future as a film star was over. He told Papi the job at the industrial plant was just temporary, and he was planning on getting back into the movies someday. Puro bullshit Papi said. And it’s true. When I met Pancho Silva he didn’t look a thing like Pedro Infante. He is full of shit, I said, and Papi agreed because he winked at me.

Papi met him at the bakery down the block from our house on TC Jester one morning when some black guy walked in with spandex on his head. Pancho was standing in front of Papi, and he turned around and said something under his breath about the spandex. Papi smiled, because he’s polite. Then Pancho started talking to him in Spanish, asking him where he was from, if he had a job. He said he could get him something at the plant he worked at because he was retiring soon and they’d need someone to replace him.

That day, Papi brought home tres leches . Mom said it was too sweet and runny and it didn’t have enough eggs. She said the one her Tía Sofi makes is the best in the world and no other tres leches comes close. You could only have a slice of this one with a cup of coffee or a glass of water to wash it down. Estrella didn’t say anything, but I could tell she liked hers because she kept licking her fork. But none of that mattered. Papi smiled and said to us, “Ya tengo trabajo.”

After his first day at work he said the plant stunk. It was hard to breathe because of the lack of air. He had to punch in at five-thirty in the morning and work until six in the evening, carrying sheets of metal and putting them where they belonged. Then push a button. Sometimes they’d ask him to help in other departments, like welding. They’d show him what to do, and he’d do it. Como un pinche perro , he’d say. He came home with his arms covered in black. Sweaty. Tired. Worn-out. And that’s when I’d get him a beer from the kitchen. I’d cut a lime and squeeze juice over it, because beer is better that way. Then I’d take a sip to make sure it tasted good. Like that, I’d get a little peda también . One beer turned into two, then three, then a six-pack. Then I started seeing a glass half-filled with Don Pedro by the couch. Sometimes at night I’d be going to sleep and hear him singing rancheras in the backyard. If I was still awake, I’d go out there and sing. I’d tell Estrella to come with me, but she’d roll her eyes and say she wasn’t a drunk Mexican like Papi.

“Mija linda,” he’d sing, his arms reaching toward the sky and his hips swaying. He’d hum some ranchera and I’d try to figure out which one it was. Mom would open the back door wearing nothing but an oversized T-shirt and tell us to be quiet before she even asked what we were doing. Papi would hit his chest with both fists, like Tarzan, like if that would make him louder, and say, “¡Aaaaaaaaaayyyyyyy, pero qué chorrito de voz tengo!” I’d laugh, and she would too. We’d laugh so hard it’d take me awhile before I could sing. Then finally, we’d sing. The same song, always, all together, all three of us.

“Paloma negra, paloma negra.”

Until I fell asleep and Papi would carry me to bed.

When we’d get ready for church it was like if misa were in some rich person’s house. Mom would spit in her hand and flatten my hair, wipe my face and say, “¡Arréglate ya, niña!”

In our room, Estrella would stand in front of our full-length mirror trying to decide what to wear. She taped photographs from teen magazines all over our walls with the singers from Menudo, Rob Lowe, and Scott Baio. It was like they were watching her as she got ready. She’d hold a curling iron above her head and count to twelve. “Why you curling your hair?” I’d ask. “They're just going to fall when you go outside.” She’d ignore me and mumble something about the color of her eyes and how she wished they were green, like Mom’s. She’d spray Aqua Net like if it were Lysol and put a barrette in her hair. Usually a bow made of ribbon. Sometimes a plastic flower.

Читать дальше