Julia says the reason I don’t say anything is because I’m in deep pain. Like if pain were something she knew looked like me. I hear her when she talks to Tencha outside my room. Because I’m eleven she treats me like some kid. The way she looks at me, feeling sorry for me, scared, but at the same time frustrated. Like if answers are overdue and behind her pity she’s upset that I’m not “cooperating.”

I used to tell You I pray for Your will. ¿Recuerdas? I used to make the sign of the cross in the dark while I was in bed and tell you how much I loved You. That I wish for the best and I pray for your will. Well, I do, but maybe I’ll smash this spider. Mom used to say that life was full of tests. And if we pass, we’ll be in Your grace. Maybe if she named me Milagro instead of Luz this would’ve never happened.

If I wait for this spider to crawl out of this room, then maybe I can go after her. And on the other side of this wall there’ll be this underwater world and I’ll swim to the deep end and float next to one of those electrical fish that light up in the dark. And maybe he’ll sting me or split me into pieces or eat me alive. But then everything will be over and no one will remember because I’ll be down there in the dark with nothing around me. With no fish, no light. No Luz.

Then what?

There’s a flea market on Alexander Street that we used to go to when I was little. It’s where we went to buy things like comales and molcajetes . They sold sheets and sheets of Lotería paper and I didn’t know it came rolled up like that. I didn’t know you could make your own tabla .

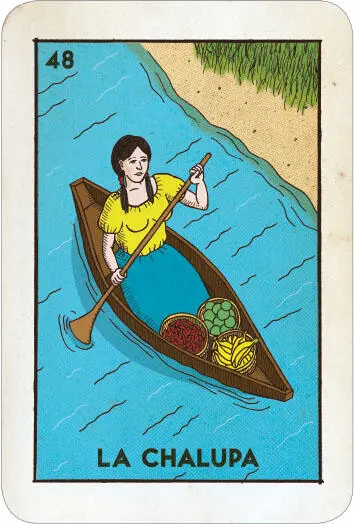

There was a round woman who sat in a canoe with flowerpots around her like if they were her children. Red flowers, pink, yellow, and purple. She wore a nightgown with thin stripes and had braids falling down her chest. Her name was Alondra. Estrella called her una pendeja because she was a grown woman dressed up like a Lotería card. But she wasn’t dumb. She made bracelets with all these different colors and would stitch your name on one if you asked. Two dollars apiece. She’d sit under the sun, even when it was ninety-five degrees outside, and braid her bracelets. We’d pass her on the way to the food stands, buy some barbacoa and tamarindo , then pass her again, and she’d be in the same place.

“Want something, Alondra? ¿Un Jarrito? ¿Algo? Ándale ,” Papi would say.

She’d close her eyes and tighten them, shake her head like if she were remembering someone who’d died. When she’d open her eyes we’d notice she wasn’t crying. “No, no gracias,” she’d say. “No necesito nada.” She’d open her arms and sweat would be glistening over her forehead.

I asked her to write a word on each bracelet I bought because I wanted them to read like a sentence. Ven. Que. Te. Quiero. Ahora . It’s the riddle to La Rosa , which is a strange dicho . I don’t know how a rose has anything to do with wanting or loving. But every time I thought of it I heard Mom’s voice and the way she’d say it in Spanish, all smooth and sexy like Sara Montiel: Come, I want you now.

And because quiero can mean either want or love, I asked if it meant “I want you” or “I love you.” Come here, because I love you, or, come here, because I want you? If you were saying to someone, come to me, then the person you loved wasn’t there, and if you had to tell someone to come to you then maybe he didn’t love you. And to want someone to come to you is like an order. If you have to order someone to come to you, how much love is in that anyway?

After Alondra made my last bracelet, I put it on my arm and she read them out loud from my wrist to my elbow. Ven. Que. Te. Quiero. Ahora . She opened her arms and hugged me the way Tencha does, with her body soft like pillows, and I understood why even though she was smiling sometimes she looked like she was in pain. She was confused of whether or not she was wanting or loving. Or both.

When Estrella ran away I thought she was going to Angélica’s house because she wanted to scare Papi into thinking she was leaving for good. We thought she was being dramatic and wanting attention. I never thought she’d go to the cops. I never thought they’d come to the house the way they did.

Julia asks the same thing over and over when she sits down next to me in the activity room. She wants to know what it was like living at home. “And on weekends?” she asks. “What did you do all together? What did you do with your Papi?” But she wouldn’t get it. She wouldn’t know what it was like.

We all fought. We all hit each other.

Papi punched because he was a man, but we hit him too. There was one time when Mom grabbed the Don Pedro bottle from the coffee table and smashed it over his head. Blood ran down his face like the statue of Jesus Christ and Estrella and I had to grab toilet paper to soak up the blood.

Now, here comes Julia thinking Fama magazine is going to open me up like some stupid jack-in-the-box. Like if I’m some extension cord tangled up in a garage she can take a few minutes to untangle. Then what? She’ll leave me alone? Or maybe Papi will stay in jail because of something I say, something she writes down and tangles up later.

It’s like in Lotería, instead of playing the four corners we play the center squares. But midway through the game you find you have the corners but you’re missing the center. And if you would’ve played the corners you would’ve won already. But that’s how it is, isn’t it?

I keep my mouth shut because I don’t know the rules of the game.

Three days ago Tencha came to visit me and sat in the chair next to the door. I’d been laying out the cards on my desk. La Rana. El Paraguas. El Melón. Thinking about the stories the cards helped me remember. Usually she sits with me on the bed and rocks me back and forth and tells me everything’s going to be okay. But this time she sat in the chair, all hunched over with her feet together, and whispered, “Mama.” Then nothing. Like if she couldn’t get the rest of the sentence out. I knew what she was trying to tell me, that her rosaries for the last week were for nothing. Her prayers to la Virgen were for nothing. And if I waited for her to tell me it would’ve taken too long. So I walked over to her and put my hand on her shoulder, and she started sobbing in that way that’s scary, like if her lungs are falling out and she has to suck them back in before they fall to the floor.

Estrella was in the ICU ever since that night they came to get Papi. I was looking out the window next to my desk when Tencha asked if I wanted to see her. She whispered, like if I’d get mad at her for mentioning her name. But she knew it wasn’t going to be the way I imagined. I wouldn’t sit at the end of Estrella’s bed and hold her hand. And I wouldn’t be able to go inside the room she was in. When Tencha said her name I put on my sneakers and stood up, keeping my head down so I wouldn’t have to see her eyes.

She had to get permission, she said. Larry, the social services director, didn’t think it was a good idea. He lowered his voice as he talked to her in the hall, but I could hear him. He said I was too fragile, it might make me worse. But she told him good, said if I didn’t get to see my sister I’d sue him when I turned eighteen. My own flesh and blood. They should be ashamed of themselves. “Shame on you!” she said. And then he agreed, but only for one night. She told him everything would be fine. She was responsible and this was a family matter.

Читать дальше