One girl had a barrel in her backyard filled with water and there was a game we played where we’d stand around it and dodge torpedoes with our hands. It was dumb, but whoever’s turn it was would splash someone and by the end we were all soaked and laughing. Estrella would look at me like if I were some wet dog and say, “You’re gonna get it when Mom sees you.”

But I’d roll my eyes and say, “No English, remember?”

We’d go to church by the plaza de San Pedro and Papi and Mom would say hi to everyone who still remembered them, because Reynosa was where they first met.

When it happened, Mom had walked into a bakery where Papi was working and ordered galletas de boda . When he told me the story he said she was the most beautiful thing he’d ever seen. He thought she was American because of how light her skin was, or from Venezuela. Anywhere but Reynosa. He gave her a box of cookies and told her there was a really good movie playing at el cine . But she didn’t respond, not at first, and so he gave her another box of cookies. And that’s when she smiled, with the second box.

He introduced himself: José Antonio, señorita. Un placer. He bowed and grabbed her hand and kissed it.

Jose Antonio Castillo .

Then she smiled and said, “Cristina. Me llamo Cristina.”

S omos iguales, mama,” Tencha says to me. “We don’t do anything but follow our hearts.”

But sometimes she’s grumpy, and I wonder if it’s because she’s not following her own. Or if it’s because she’s never been married or because her hair is gray and she doesn’t color it. Whenever I get close to her I notice the whiskers on her chin. But when she looks at me I can see how much she loves me. She calls me her life, su vida . She hasn’t found a man to spend her life with and deep down I think she’s lonely, even though she says she doesn’t need anyone to make her happy.

Mom used to say she didn’t get along with Tencha. She couldn’t figure out why and there was no good reason, but they just didn’t see eye to eye. And that’s why Estrella argued with Tencha all the time. She liked acting like she was white and I think it bothered Tencha. She had dark skin like me and Papi, and she reminded Estrella that even though she wasn’t dark she was still Mexican. Estrella would tell me how much she hated her and call her una pinche gorda. Una india, like those women in the streets selling baskets and bracelets.

Tencha would speak softer to her after that. Because of course it hurt her feelings. How can you call someone fat and not expect them to get hurt? Her eyes would get red and she’d explain to Estrella that she thought her manners were not like those of a young lady. But Estrella wouldn’t listen. Later in our room she’d tell me how funny it was when Tencha got all serious, and that’s when I wanted to hit her.

There’ve been times when Tencha’s called my name and I haven’t felt like going to her. But I go to her anyway, and she’s sitting on the couch with her arms open, like she’s ready to squeeze the life out of me. “Mira quién es,” she says. Then I’m covered in her. We sway back and forth, back and forth like on a boat, and she says again, “Mira quién es, mira quién está conmigo.”

The throbbing went through my arms and down my legs and through my veins and back up again into my chest. We had come back from Reynosa a few weeks earlier and Memo had already blown up his hand. I was sitting in front of the television. Papi yanked me away from the couch and dragged me by my hair into the kitchen with his veins coming out from around his nose. You would think Memo wouldn’t have said anything, but maybe he did, maybe it slipped. Maybe Tío Carlos told Papi I’d given Memo a blow job. But I didn’t. I didn’t put anything in my mouth. I touched him and that was it.

Sometimes the bones in my hand beat from the inside like they did that night and I can remember the moment it broke, when Papi told me to bang my hand against the wall, like in Nosotros los pobres , after Pedro Infante slaps Chachita across the face. He bangs his hand against the wall until it bleeds, until it breaks, and she screams, “¡No! ¡No, Papi! ¡No hagas eso!”

“¡Fuerte!” Papi yelled. “¡Dale chingasos!”

He stood over me and everything looked like it was behind water. Mom ran into the kitchen from the hallway, kind of dumb, not knowing what to do or what was going on. Estrella ran to our room looking at me from the doorway before she turned the corner. Mom tried to stop Papi from grabbing my arm but he pushed her away and started saying what I’d done. He screamed that I’d grabbed su pinche cosa. He looked at me and yelled, “¿Y qué hiciste?” He wanted me to say it. He wanted me to confess. “What did you do? ¿Qué hiciste? ” He called me putita . “Is that what you are? ¿Una putita? ¿Eh? Pégale, chingada madre. ¡Ándale! ” He screamed that I jacked him off, my own cousin, my own hand. Seven fucking years old! And I had to learn a lesson. “¡Pégale! ¡Ándale!” He grabbed my elbow and banged my hand against the wall. Mom stepped in between us but he slapped her so hard she fell over the counter. We were standing next to the backdoor and the steps that went down to the backyard. I remember the wind coming in making the screen door hit against the frame. Papi pushed me against the wall, and when I stood up he pushed me again toward the door. I fell down the stairs and caught myself on the concrete outside. That’s when I noticed my hand dangling from my wrist like an animal hanging off a branch. I grabbed it with my other hand, trying to hold it up. Mom ran out holding her face, and I could see Estrella peeking from our bedroom window that looked out into the backyard. Papi, grabbing his hair with his fists, didn’t look like himself anymore.

We got in the truck and drove to the hospital next to the highway. But the throbbing didn’t stop and I could hear the beating in my ears. It didn’t stop in the waiting room or when the doctor looked at it, or when they wrapped it and told us to come back the following day so they could fix it. It didn’t stop until later, much later, after I closed my eyes and passed out from whatever they gave me to kill the pain.

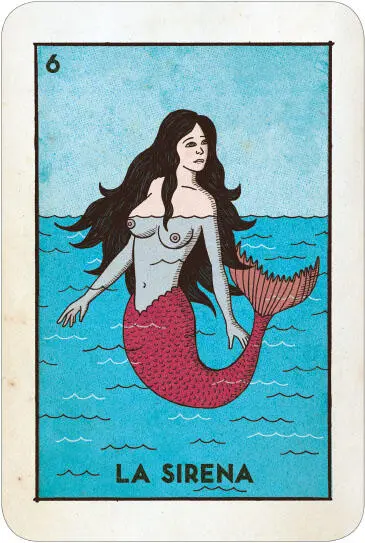

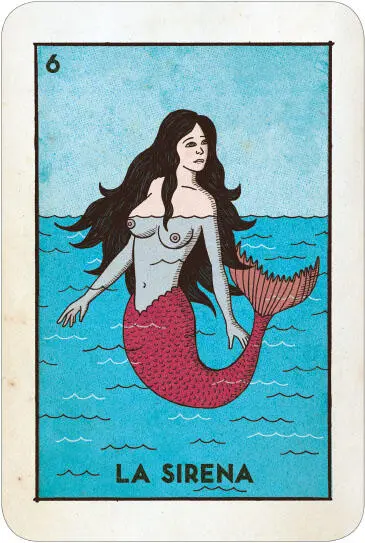

Whenever La Sirena was called, I’d look at her above the water with her arms down by her side and her long, wavy hair, wishing I was her. Not because she was pretty or grown-up but because wherever she lived nothing and no one could touch her and she could swim wherever she wanted.

I waited until everyone was inside, always at night when they were sitting on the couch watching late-night television at Tencha’s house. She lived a block away from us. I’d wrap two towels around my legs and overlap them to cover my feet, then tie string from my ankles to my knees before rolling into her pool from the shallow end. It was a shitty pool that came with the house she rented, but it was five feet deep and enough to get lost in. The towels would soften around my legs and the extra material that fell over my feet would feel like the fins from a goldfish. I’d wiggle from one side of the pool to the other, humming a song with my eyes wide open, not knowing whether I was crying or not because I was underwater, and I’d dare myself to stay there for as long as I could.

Читать дальше