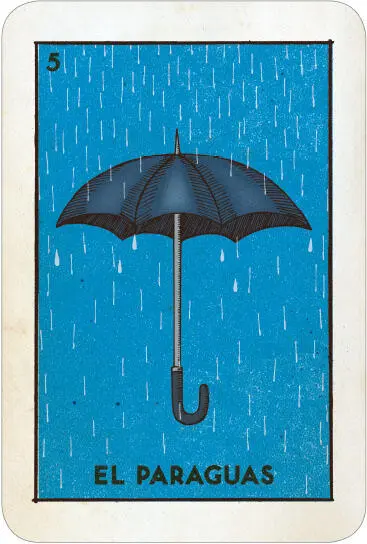

We used Sharpies to write our names on the back of our boards. Miriam covered the back of hers with bubble letters and Luisa drew flowers over the “I” in hers. Gastón wrote “Property of Gastón Silva” in the corner with such neat handwriting you could tell he was trying to make it perfect. Some tablas weren’t even glued on cardboard to keep them stiff. They were just sheets of paper and they curled like pencil shavings. Some had people’s names on the back I didn’t recognize. Like Marcella. Who was she? Luisa would sometimes take her tabla during a game and bet three quarters on it, to try her luck. And she’d win! I remember Marcella’s name because her tabla was always the lucky one. Whoever played it would win at least three or four times.

Once everyone arrived at Buelita Fe’s house we’d walk down the block and attend ten o’clock mass at La Iglesia de San Miguel. I never wanted to go because it was held in Spanish. I understood but I never felt like listening. Instead I’d look up at the ceiling at the yellow glass dome that would glow like a lamp. And when I’d forget where I was it’d be time to kneel. Or stand up. Or kneel down again. Say amen. Why do we have to kneel down and stand up so many times? When it was time for communion Mom would walk to the line at the back where the double doors were. I’d want to go with her so I could move my legs but she’d push me down and say, “Uh-uh, mija . You haven’t done your communion yet.” And I’d act all stupid. “What’s that?”

“When you know who Diosito is.”

Like if I didn’t know.

Papi would be dozing off next to me, trying to keep his back straight, and Estrella would be between us, on her knees acting as though she were praying. She hadn’t done her communion either, but she was studying for it. She’d been going to Thursday night classes learning the Act of Contrition.

I’d watch Mom walk down the aisle and her curls would bounce and her dress would move like stirring milk. She’d bow her head and move her lips when she stood in front of Padre Félix, then whisper “Amen,” open her mouth, and take the wafer. She’d excuse herself to the people in our pew and kneel down next to me, acting all serious, without smiling, like if You were keeping an eye on her. I’d look around and see everyone acting serious, so serious that when it was time to sing they kept their voices down, embarrassed they might be off-key.

I’d pull on Mom’s dress but she wouldn’t move. Her elbows would be on the back of the pew in front of her and her forehead would be resting on her knuckles. Her eyes would be closed and her lips would hardly move. Sometimes I wondered if she were praying because of something she’d done to Papi. Or something he’d done to her. Or maybe she felt bad for calling him names or for hitting him with something she grabbed from the kitchen drawer. I wanted to let her know that it was okay and that You’d understand. I pulled on her dress but she reached out and pinched me without even looking. I didn’t even know what happened, but I remember my skin burning and thinking how much I hated her. I called her names and stuck out my tongue when she wasn’t looking even though You were right there between us. But I only hated her for as long as I could feel the sting on my arm.

Tencha once told me we should be careful of what we think and do because You see us better than we see ourselves. Sometimes You find a way inside us to show us who we really are. But you have to let him in, she says. You have to open your heart.

After a lot of kneeling and praying misa would end and everyone would walk out the front doors, giving anyone they passed a handshake. Estrella would hold Mom’s hand with her chin up like if we were about to take pictures.

Outside, if it wasn’t raining, people would give thanks to Padre Félix like if he were some movie star. There’d be a crowd waiting to grab his hands, and Papi would give thanks to him too, but then he’d wait on the side and I’d stand next to him, smelling his sleeve, waiting to leave. Sometimes Mom would make me go give thanks. And I would, because I had to.

But then, we’d all walk to Buelita Fe’s, and she’d say the sopita was ready. Pancho would puff up his chest and tell us about the spices he used to rub over the steaks we were going to eat. I’d start to hear the clicks of beer cans going off every few minutes from my tíos sitting by the garage, under the patio, and the voices of my cousins running around the house, chasing each other. And after we were done eating fajitas and frijoles and elote , we’d sit at the long table made of three other tables pushed together. Some of us on stools, some of us in chairs. We’d take out the jar of pinto beans and bottle caps and loose change so we could play Lotería . We’d lay out the tablas and choose the ones we wanted. Some of us with two, some of us with four. We’d play a round and fill a vertical line, then a horizontal, two diagonals making an X. And then the corners. Las Esquinas . And once we were crowded around the table with our necks stretched to see the pile of cards being dealt, La Chalupa, El Pescado, El Cazo , we’d play a round of blackout. And by then the game would’ve gotten faster and louder and it’d be hard to keep up with the images stacking up in the middle of the table. Whoever was dealing would throw them down and sing the riddles and someone would miss a card. They’d scream, “Wait! Slow down, chingao ! What was the last one?” But we’d keep going. We’d play until the sun outside didn’t even seem bright anymore, until one of us had everyone else’s money, a bulge of quarters and nickels and dimes kept in a Ziploc bag, where it was kept until the following Sunday, when we’d take out our tablas and bottle caps and loose change, and do it all over again.

Iused to run outside when it rained and get so wet it didn’t seem like it was raining anymore. I’d run to the back of our neighborhood where there were trails I thought led somewhere. And by the time I came back, I’d be soaked. Mom would rip my clothes off right there in the middle of the kitchen, all mad because she hadn’t even known I’d snuck out through our bedroom window.

There was one time Estrella was at the kitchen table drawing or coloring or doing whatever she was doing with paper and scissors. She made a purse out of red construction paper and it opened up like an accordion with a yellow tassel glued at the end. I told her it was pretty, but only a cunt would wear it. Mom turned and looked at me like if I’d dropped a glass. She was wringing my shorts and I was standing there in my underwear, dripping.

“What did you say?” she asked. “Do you know what that means?” I shrugged, but before I dropped my shoulders she slapped me across the face. Not on my cheek but on the side of my eye. I stared at her and she stared at me, like if we were bad actresses in a telenovela .

Papi came into the kitchen, “¿Qué chingado está pasando?” Estrella had scissors in her hand with the ends pointing up, her mouth was half-open. I didn’t know what to do with them looking at me, so I ran out the door and through the yard. I pushed my hair out of my face because I was drowning in it and all I could taste was rain. I heard Papi scream, “¡Luz! Ven, mija.” But I kept running. I was seven I think, and it was the first time Mom ever hit me.

I could see her face as I ran, the way she looked at me after she hit me. And it didn’t hurt and it didn’t matter. It was how she looked at me. Like if she knew she was wrong and didn’t want me to know it. I couldn’t understand what her problem was. People said it at school. I was a cunt. She was a cunt. My teacher at school was a cunt. It was like saying pinche or pendejo . Like when she’d call Papi un hijo de puta . There was no reason to slap me just because of a word.

Читать дальше