Directing external collaboration

Traditional business relationships are transactional and often self-centered. Buyers and suppliers approach each deal as a win-lose game: The suppliers are trying to inflate their profits, and the buyers are trying to squeeze them on price. Over the long run, this approach can damage both parties because it destroys value rather than creates it. To build sustainable supply chain relationships, each partner needs to look for opportunities to contribute more value. The goal is for each to identify ways to share value, maximize total value, and be successful over the long term. This approach is very different from a transactional approach, in which each party is trying to squeeze every penny from each deal even if it means causing harm in the long run.

Applying project management

Supply chains are dynamic. Companies respond to changes with projects, so the last step in the New Supply Chain Agenda is implementing strong project management capabilities. Teaching people how to manage projects well and having professional project managers involved are the keys to ensuring that your supply chain evolves as your customers, suppliers, and company change.

I provide a whole section about leading supply chain projects in Chapter 4.

I provide a whole section about leading supply chain projects in Chapter 4.

Chapter 2

Understanding Supply Chains from Different Perspectives

IN THIS CHAPTER

Looking at the three flows in every supply chain

Looking at the three flows in every supply chain

Aligning key supply chain functions and groups

Aligning key supply chain functions and groups

Designing and monitoring supply chain performance

Designing and monitoring supply chain performance

There are several ways to analyze what’s happening in a supply chain. Each of these perspectives can help you understand how your supply chain really works and reveal opportunities for improvement. Because there are so many ways to look at the same issue, supply chain managers can encounter confusion and miscommunication about which options are the best. In this chapter, you see several of these approaches and examples that illustrate how useful they can be for managing your own supply chain.

Managing Supply Chain Flows

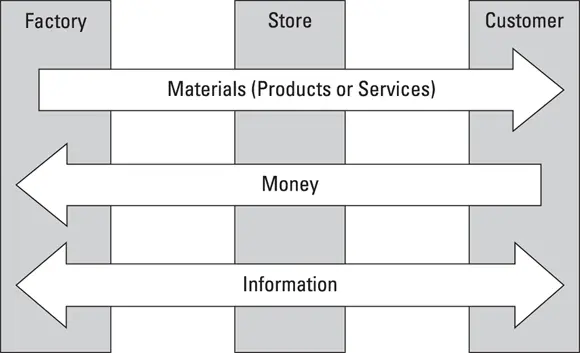

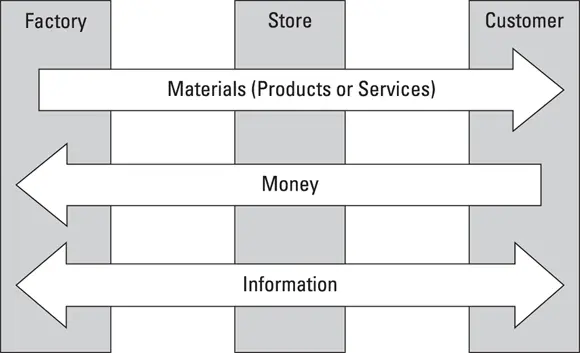

One great way to explain a supply chain is to think of it as three rivers that flow from a customer all the way back to the source of raw materials. These rivers, or flows, are materials, money, and information, as shown in Figure 2-1. Materials flow downstream in the supply chain, starting with raw materials and flowing through value-added steps until a product finally ends up in the hands of a customer. Money flows upstream from the customer through all the supply chain partners that provide goods and services along the way. Information flows both upstream and downstream as customers place orders and suppliers provide information about the products and when they will be delivered.

FIGURE 2-1:Three supply chain flows.

Managing a supply chain effectively involves synchronizing these three flows. You have to determine, for example, how long you can wait between the time when you send a physical product to your customer and when the customer pays you for the product. You also have to determine what information needs to be sent each way — and when — to keep the supply chain working the way you want it to.

Every dollar that flows into a supply chain comes from a customer and then moves upstream. The companies in the supply chain have to work together to capture that dollar, but they’re also competing to see how much of that dollar they get to keep as their own profit.

Every dollar that flows into a supply chain comes from a customer and then moves upstream. The companies in the supply chain have to work together to capture that dollar, but they’re also competing to see how much of that dollar they get to keep as their own profit.

Synchronizing Supply Chain Functions

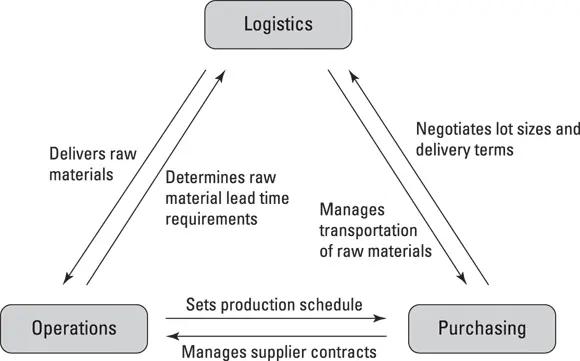

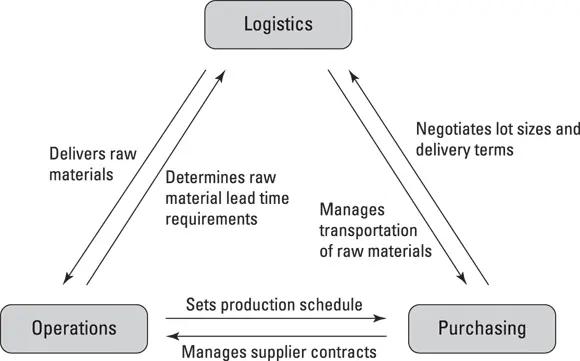

Supply chain management can also be described as integrating three of the functions inside an organization: purchasing, logistics, and operations. Each function is critical in any company, and each has its own metrics. Because these functions are interdependent (see Figure 2-2), making good decisions in any of these areas requires coordination with the other two.

The purchasing, logistics, and operations teams often have conflicting goals —often without realizing it. Managing these functions independently leads to poor overall performance for your company. To meet top-level goals, supply chain managers need to make sure that the objectives of these groups are aligned.

The purchasing, logistics, and operations teams often have conflicting goals —often without realizing it. Managing these functions independently leads to poor overall performance for your company. To meet top-level goals, supply chain managers need to make sure that the objectives of these groups are aligned.

FIGURE 2-2:Logistics, purchasing, and operations are interdependent.

The simplest top-level goal for many supply chain decisions is return on investment. Focusing on this one objective can often help everyone see the big picture and look beyond functional supply chain metrics such as capacity utilization or transportation cost.

The simplest top-level goal for many supply chain decisions is return on investment. Focusing on this one objective can often help everyone see the big picture and look beyond functional supply chain metrics such as capacity utilization or transportation cost.

Purchasing (or procurement ) is the function that buys the materials and services that a company uses to produce its own products and services. The basic goal of the purchasing function is to get the stuff that the company needs at the lowest cost possible; the purchasing department is always looking for ways to get a better deal from suppliers. Some of the most common cost-reduction strategies for a purchasing manager are

Negotiating with a supplier to reduce the supplier’s profit margin

Buying in larger quantities to get a volume discount

Switching to a supplier that charges less for the same product

Switching to a lower-quality product that’s less expensive

On the surface, any of these four options looks like a simple, effective way to reduce costs and therefore increase profitability, but each can have negative long-term effects. Driving a supplier’s profit margin too low, for example, could make it hard for them to pay their bills — or even force them out of business. Although you’d save money in the short term, having to find a new supplier in the future could cost you a lot more, increasing your total cost. Many purchasing decisions can also have direct effects on the costs of other functions within your company. Sourcing lower-quality raw materials might lead to higher inspection and testing expenses, for example.

Your total costs include all the investments and expenses that are required to deliver a product or service to your customer.

Your total costs include all the investments and expenses that are required to deliver a product or service to your customer.

Читать дальше

I provide a whole section about leading supply chain projects in Chapter 4.

I provide a whole section about leading supply chain projects in Chapter 4. Looking at the three flows in every supply chain

Looking at the three flows in every supply chain

Every dollar that flows into a supply chain comes from a customer and then moves upstream. The companies in the supply chain have to work together to capture that dollar, but they’re also competing to see how much of that dollar they get to keep as their own profit.

Every dollar that flows into a supply chain comes from a customer and then moves upstream. The companies in the supply chain have to work together to capture that dollar, but they’re also competing to see how much of that dollar they get to keep as their own profit.