Logistics covers everything related to moving and storing products. This function involves physical distribution, warehousing, transportation, and traffic.

Inbound logistics refers to the products that are being shipped to your company by your suppliers. Outbound logistics refers to the products that you ship to your customers.

Logistics adds value because it gets a product where a customer needs it when the customer wants it. Logistics costs money too. Transporting products on ships, trucks, trains, and airplanes has a price tag. Also, whether a product is sitting on a truck or gathering dust in a distribution center, it’s an asset that ties up working capital.

The goals of the logistics function are to move things faster, reduce transportation costs, and decrease inventory. Following are some ways that a logistics department might try to achieve these goals:

Consolidating many small shipments into one large shipment to lower shipping costs

Breaking large shipments into smaller ones to increase velocity

Switching from one mode of transportation to another, either to lower costs or increase velocity

Increasing or decreasing the number of distribution centers to increase velocity or lower costs

Outsourcing logistics services to a third-party logistics (3PL) company

You can see the conflicts that can occur between logistics and purchasing. Logistics wants to decrease inventory, which may mean ordering in smaller quantities, but purchasing wants to lower the price of the purchased materials, which may mean buying in larger quantities. Unless purchasing and logistics coordinate their decision-making and align their goals with what’s best for the bottom line, the two functions often end up working against each other and against the best interests of your company, your customers, and your suppliers.

Operations is the third key function in supply chain management, involving the processes that your company focuses on to create value. Here are some examples:

In a manufacturing company, operations manages the production processes.

In a retailing company, operations focuses on managing stores.

In an e-commerce company or 3PL, the operations team may also be the logistics team.

Operations managers usually focus on capacity utilization, which means asking “How much can we do with the resources we have?” Resources can be human resources (people) or land and equipment (capital). The operations department is measured by how effectively and efficiently it uses available capacity to produce the products and services that your customers buy. Common goals for operations teams include

Reducing the amount of capacity wasted due to changeovers and maintenance

Reducing shutdowns for any reason, including those caused by running out of raw materials

Aligning production schedules and orders for raw materials with forecasts received from customers

Although increasing operations efficiency sounds like a great idea, sometimes it actually creates supply chain problems and does more harm than good. Companies may invest in increasing their capacity only to find out that their suppliers or logistics infrastructure can’t support the higher production levels or that they’re making more product than they can sell.

Connecting Supply Chain Communities

If you’ve ever taken a personality test, such as the Myers-Briggs Type Indicator, you know that these tests can reveal important differences in the way that people approach problems and make decisions. It turns out that groups of people have personalities too. These personalities form the culture of a group, and culture matters a lot when it comes to managing a supply chain.

Suppose that one of your customers is a company that really values reliability. That company considers it important for a supplier to deliver exactly what was ordered, exactly the same way, every time. The culture of that group — the things that the company values — determines how it judges its suppliers. Now suppose that this customer has a choice of working with two suppliers: one that’s known for consistent quality and another that’s known for flexibility and innovation. Naturally, the first supplier would be a better cultural fit because of the value that the customer places on reliability.

The impact of culture can also apply to the functions within your organization. Different departments — such as purchasing, logistics, and operations — often develop cultures of their own. If the values of these departments clash, it’s difficult for the company to manage its supply chain effectively.

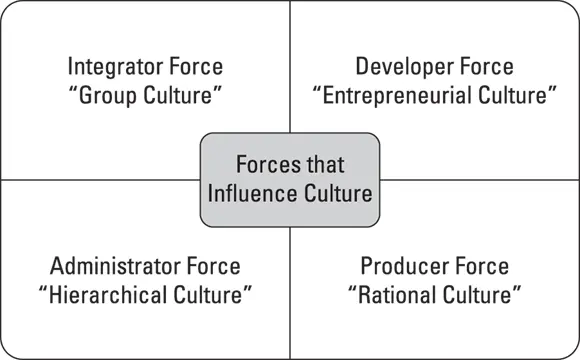

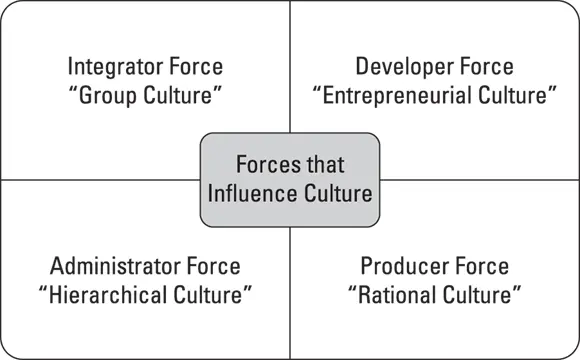

One useful way to think about the culture of a company or a department is to use a framework that was developed by John Gattorna in Dynamic Supply Chains: Delivering Value through People, 2nd Edition (FT Press, 2010). Gattorna says that four major behavioral forces determine the culture of a group (see Figure 2-3) and are often related to the style of a group’s leader and the norms of a particular industry:

Integrator: Force for cohesion, cooperation, and relationships

Developer: Force for creativity, change, and flexibility

Administrator: Force for analysis, systems, and control

Producer: Force for energy, action, and results

FIGURE 2-3:Dominant group personalities.

The strength of these personality forces leads to differences in the culture of a team or organization. The most accurate way to measure culture is to formally interview people on a team and then analyze their responses. But in many cases, you can get a good sense for a team’s culture simply by working with the team for a little while.

Teams that are driven by the Integrator force tend to have a group culture, in which everyone is encouraged to develop personal relationships and informal communications. In a group culture, people feel that they’re part of a family. But a group culture also tends to be exclusive: the team against everyone else.

Teams that are driven by the Developer force form an entrepreneurial culture, in which everyone focuses on realizing a common vision. Communications are informal, and ideas are exchanged with people inside and outside the group. An entrepreneurial culture may tolerate bad behaviors that don’t interfere with achieving the shared goal.

Teams that are driven by the Administrator force create a hierarchical culture, in which communication is formal and shared through official channels. Hierarchical cultures are good at developing processes and ensuring consistency, but they’re often slow and inflexible.

Teams that are driven by the Producer force develop a rational culture, in which communications are concise and fast. Plans are made, plans are executed, and updates are sent out to keep stakeholders in the loop. Rational cultures are good at keeping teams focused and delivering results. But these cultures often find it hard to deviate from a plan, even when the circumstances around them change.

A useful exercise for analyzing your supply chain is to list the groups that work together and try to determine the dominant culture of each group. This exercise can help you anticipate conflicts that might emerge when these groups interact and find ways to use differences to your advantage. Here are some examples:

Purchasing departments often have a hierarchical culture, whereas operations departments have a rational culture. The purchasing department may feel frustrated because operations doesn’t follow the rules. Operations may feel frustrated because purchasing is slowing it down. So you could create a small team of expeditors, made up of representatives of both operations and purchasing, to manage urgent orders while ensuring that all the proper policies are followed.

Читать дальше