You work for a wholesaler that has been selling a product at a steady rate for months, and one month, the company sells twice as much as normal. You don’t have enough inventory to fill all your customer orders, and now you also have back orders to fill. You may even be at risk of losing sales and customers. You might decide to place bigger orders in the future and keep more inventory on hand. That means you’ll be investing more working capital in inventory, and if sales drop off in the future, you’ll have to figure out what to do with that extra inventory.

You work for a transportation company. The company’s customers pay you to deliver their products around the world, and they count on your deliveries to help them meet their commitments to their own customers. Therefore, your ability to deliver on time is essential to them. Suddenly, a volcano in a distant part of the world spews ash far into the sky, making it dangerous for airplanes to use a heavily traveled flight path. You could reroute your planes, but this process is an expensive one that involves developing flight plans, scheduling airplanes, and finding available crews. Alternatively, you could tell your customers that their deliveries are on hold until normal operations can resume.

Thousands of companies have had to face every one of these scenarios in the past few years. In every case, making the right decision about how to respond requires understanding supply chains and supply chain management.

You can find more information about supply chain scenario planning, as well as a link to the MIT Scenario Planning Toolkit, in Chapter 18.

You can find more information about supply chain scenario planning, as well as a link to the MIT Scenario Planning Toolkit, in Chapter 18.

Some supply chain management professionals are generalists, and others are specialists. Generalists look at the big picture; specialists focus on a particular step in the supply chain. A good way for you to start learning about supply chain management is to think like a generalist and become comfortable with some of the general principles.

The next sections cover ten supply chain management principles, five supply chain tasks, and the five steps for implementing a new supply chain agenda. Each section provides a slightly different perspective on supply chain management, but the sections explain the same challenge in different ways. The supply chain management principles express the essence of supply chain management. The five supply chain tasks are like the job description of a supply chain manager. And the New Supply Chain Agenda is a strategy for planning and implement effective supply chain management practices.

Operating Under Supply Chain Management Principles

Many people try to define supply chain management by talking about what they do, which is a bit like describing a cake by giving someone a recipe. A different approach is to explain what supply chain management creates. To continue the cake analogy, that approach communicates how the finished cake tastes and what it looks like.

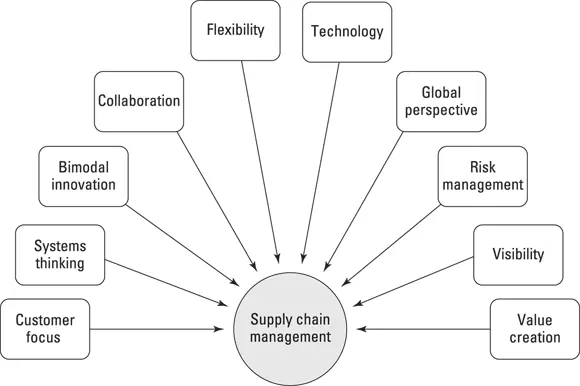

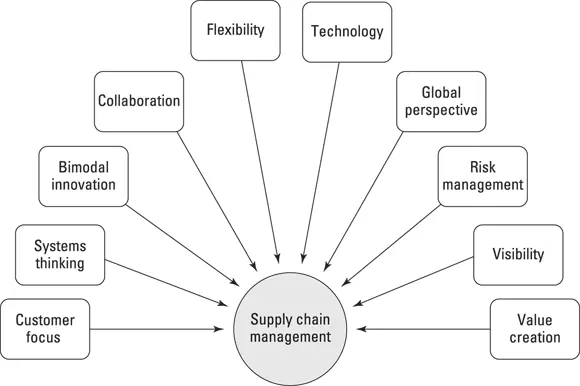

The key supply chain management principles illustrated in Figure 1-3 are good places to start.

FIGURE 1-3:Supply chain management principles.

Supply chain management starts with understanding who your customers are and why they’re buying your product or service. Any time customers buy your stuff, they’re solving a problem or filling a need. Supply chain managers must understand the customer’s problem or need and make sure that their companies can satisfy it better, faster, and cheaper than any competitors can.

Supply chain management requires understanding the end-to-end system — the combination of people, processes, and technologies that must work together so that you can provide your product or service. Systems thinking involves appreciation of the series of cause-and-effect relationships that occur within a supply chain. Because these systems are complex, supply chains often behave in unpredictable ways, and small changes in one part of the system can have major effects somewhere else.

The world of business is changing quickly, and supply chains need to keep up by innovating. Two kinds of innovation are important for supply chains:

Sustaining innovation: Sustaining innovation is built on continuous process improvement techniques such as Lean, Six Sigma, and the Theory of Constraints (see Chapter 4). Sustaining innovation isn’t sufficient, though, because new technologies can disrupt industries. So you also need to pursue disruptive innovation.

Disruptive innovation: Disruptive innovation introduces a product, process, or service that creates new markets and destroys established paradigms. When a disruptive solution is accepted, it becomes the new dominant paradigm. If you’re in the business of making buggy whips, you need to figure out how to make buggy whips better, faster, and cheaper than your competitors do, as well as what the new dominant paradigm is going to be so that you’ll know what to do when buggy whips are replaced by a different technology.

Supply chain management can’t be done in a vacuum. People need to work across departments inside an organization, and they need to work with suppliers and customers outside the organization. A “me, me, me” mentality leads to transactional relationships in which people focus on short-term opportunities while ignoring the long-term results. This situation costs more money in the long run because it creates lack of trust and unwillingness to compromise. An environment in which people trust one another and collaborate for shared success is much more profitable than an environment in which each person is concerned only with his or her own success. Also, a collaborative type of environment makes working together a lot more fun.

Because surprises happen, supply chains need to be flexible. Flexibility is a measurement of how quickly your supply chain can respond to changes, such as an increase or decrease in sales or an interruption of supply. This flexibility often comes in the form of extra capacity, multiple sources of supply, and alternative forms of transportation. Usually, flexibility costs money, but it also has value. The key is understanding when the cost of flexibility is a good investment.

Suppose that only two companies in the world make widgets, and you need to buy 1,000 widgets per month. You may get a better price on widgets if you buy all of them from a single supplier, which would lower your supply chain costs. But you’d have a problem if that supplier experienced a flood, fire, or bankruptcy. You may save some money at first, but you’re stuck if anything goes wrong with that supplier.

If you established a relationship with the second supplier by buying some of your widgets from them — even at a higher cost — you wouldn’t be hurt as badly if the first supplier stopped making widgets. Having a second supplier provides flexibility.

Think of the extra cost that you pay to the second supplier as a kind of insurance policy. You’re paying more up front, but you’re increasing your supply chain flexibility and protecting yourself from a possible disruption.

Think of the extra cost that you pay to the second supplier as a kind of insurance policy. You’re paying more up front, but you’re increasing your supply chain flexibility and protecting yourself from a possible disruption.

Читать дальше

You can find more information about supply chain scenario planning, as well as a link to the MIT Scenario Planning Toolkit, in Chapter 18.

You can find more information about supply chain scenario planning, as well as a link to the MIT Scenario Planning Toolkit, in Chapter 18.