Jing-Feng Li - Lead-Free Piezoelectric Materials

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Jing-Feng Li - Lead-Free Piezoelectric Materials» — ознакомительный отрывок электронной книги совершенно бесплатно, а после прочтения отрывка купить полную версию. В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: unrecognised, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Lead-Free Piezoelectric Materials

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Lead-Free Piezoelectric Materials: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Lead-Free Piezoelectric Materials»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Lead-Free Piezoelectric Materials

Lead-Free Piezoelectric Materials

Lead-Free Piezoelectric Materials — читать онлайн ознакомительный отрывок

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Lead-Free Piezoelectric Materials», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

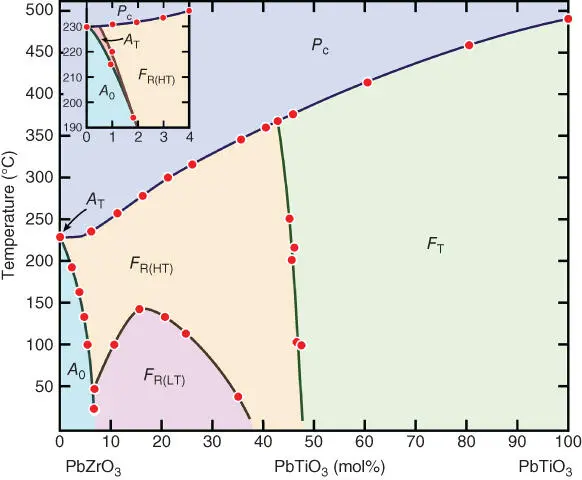

Figure 2.1 Phase diagram of the PbZrO 3–PbTiO 3system. Note that there are revised phase diagrams showing an area instead of a line in the middle composition.

In addition to the existence of MPB, the properties of PZT ceramics can be adjusted relatively easily by chemical doping or substitution, which made PZT like “all‐around player” to meet a wide range of applications. In fact, piezoelectric ceramic devices can be classified as actuators, sensors, and transducers, which have specific property requirements. For example, “hard” PZT ceramics for high‐frequency transducers actuators need high mechanical quality factor ( Q m), but sensors usually use “soft” PZT with enhanced d 33. All kinds of PZT ceramics are commercially available. However, the large amount of lead contained in PZT materials has drawn much attention during the past decade, due to the environmental concern as well as governmental regulations against hazardous substances. In 2006, the European Union has already adopted the well‐known directives: Waste Electrical and Electronic Equipment (WEEE) and Restriction of the use of certain Hazardous Substances (RoHS) in electrical and electronic equipment, with the purpose of protecting human health as well as environment by exclusion or substitution of hazardous substances used in electrical and electronic devices [8]. Similar regulations have also been planned or established in North America, Japan, Korea, and China. Lead ranks foremost among the hazardous substances list due to its notoriety, with maximum allowed concentration of merely 0.1 wt%. Bearing the goal to reduce the production and waste disposal of toxic lead, the research on lead‐free piezoceramics strives to make PZT and similar perovskite materials redundant. Substantial effort has been devoted to the development of high‐performance lead‐free piezoelectric ceramics based on the several perovskite compounds [9], including BaTiO 3, (K,Na)NbO 3, (Bi 0.5Na 0.5)TiO 3, and BiFeO 3. In particular, great progress has been made since 2004 when Saito et al. reported (K,Na)NbO 3based lead‐free piezoelectrics with properties comparable with those found in PZT [10].

This chapter is set up to enable the readers quickly learn about the lead‐free piezoelectrics by introducing their brief history, crystal structure, and physical natures for BaTiO 3, (K,Na)NbO 3, (Bi 0.5Na 0.5)TiO 3, and BiFeO 3systems. We first introduce BaTiO 3not only because it is the first lead‐free ferroelectric compound, but also for the purpose to show the intrinsic role of Pb by comparing BaTiO 3with PbTiO 3, which is a representative lead‐containing ferroelectric. The detailed research progress about each system will be given in Chapters3–7.

2.2 BaTiO 3

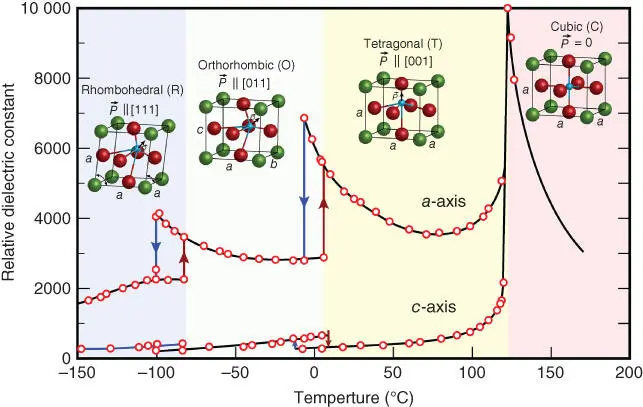

BaTiO 3is a well‐known ferroelectric material that was discovered before PZT in the 1940s during the World War II [11]. Before the emergence of PZT, BaTiO 3had been the most important piezoelectric material, which has a higher piezoelectric coefficient d 33= 120–190 pC/N than that of preceding piezoelectric materials such as triglycine sulfate (TGS), potassium dihydrogen phosphate (KDP), and quartz. BaTiO 3undergoes a series of phase transitions, from cubic to tetragonal approximately at 130 °C, then to orthorhombic at 0 °C, and further to a rhombohedral crystal structure at −90 °C, as shown in Figure 2.2[12].

Although BaTiO 3is the first lead‐free piezoelectric compound, its Curie point (approximately 130 °C) is moderate, which limits its piezoelectric applications. Nevertheless, there are also many studies on lead‐free piezoelectrics based on BaTiO 3[13, 14]. High piezoelectricity has been reported in pure BaTiO 3single crystals [15, 16] and fine‐grained ceramics [17, 18]. In 2009, Liu and Ren reported a large piezoelectric response for the BaTiO 3‐based ceramic system with a d 33coefficient >600 pC/N [19], which is comparable with soft PZT ceramics. The details will be given in Chapter 5.

BaTiO 3is often used as a model ferroelectric material for fundamental studies because of its simple composition and rich phase structures. For example, early studies have been conducted to reveal the role of Pb from a comparison between BaTiO 3and PbTiO 3[20]. Both compounds have similar cohesive properties such as unit‐cell volume (0.0632 and 0.0642 nm 3, respectively), yet with distinct ferroelectric behavior. PbTiO 3has a high Curie temperature of 490 °C, and a large value of spontaneous polarization P s(57 μC/cm 2), whereas those of BaTiO 3are much lower ( P s~ 26 μC/cm 2). PbTiO 3has no low‐temperature phase transitions, whereas BaTiO 3is known to have successive phase transitions, from the cubic structure to tetragonal, orthorhombic, and rhombohedral structure at low temperature. To explain why BaTiO 3and PbTiO 3show different ferroelectric behaviors, the studies have been focused on the difference in the chemical bonds of the two perovskite compounds. Kuroiwa et al. demonstrated through calculations that the Pb and O electronic states hybridize in tetragonal PbTiO 3, whereas the interaction between Ba and O is almost purely ionic in the tetragonal BaTiO 3, as shown by the charge‐density distributions of cubic and tetragonal PbTiO 3and BaTiO 3in Figure 2.3[20]. It clearly revealed that no apparent difference can be seen between the cubic phases of PbTiO 3and BaTiO 3, but between their tetragonal phases. Within the latter phases, the distributions in the Pb–O and Ti–O planes of PbTiO 3are significantly different from those in the Ba–O and Ti–O planes of BaTiO 3. The electron‐density distribution around the Pb and O2 sites in tetragonal PbTiO 3is quite anisotropic as shown in Figure 2.3c, i.e. extending toward the O2 and Pb, respectively. The electron densities of Pb and O2 are overlapped along the Pb–O2 direction in the tetragonal PbTiO 3. However, the electron densities around Ba and O are isotropic for tetragonal BaTiO 3, as shown in Figure 2.3a. These results indicate that the PbO bonds of tetragonal PbTiO 3are covalent, although they are ionic in the cubic phase. By comparing Figure 2.3b,d, it is clear that the Ti in PbTiO 3has a larger displacement than that in BaTiO 3, consistent with the fact that the spontaneous polarization of PbTiO 3is larger than that of BaTiO 3. This provides clear evidence for the Pb–O hybridization in tetragonal PbTiO 3, which has been theoretically predicted as a key factor of much larger ferroelectricity of PbTiO 3as a representative Pb‐containing ferroelectric compound than that of BaTiO 3as a lead‐free counterpart.

Figure 2.2 Change in relative dielectric constants of BaTiO 3ceramics as a function of temperature. Inserted are the crystal structures at the corresponding temperatures.

Source: Modified from Merz [12].

The aforementioned comparison between BaTiO 3and PbTiO 3indicates that partial covalent bonding due to the Pb–O hybridization should be responsible for the high performance of Pb‐containing piezoceramics. In lead‐free counterparts, Saito et al. also found that substituting Nb with Sb, which has higher electronegativity than the former, leads to further piezoelectric property enhancement in (K,Na)NbO 3‐based ceramics [10]; this is also because of the hybridization of covalency onto ionic bonding. In addition, Bi as a neighbor of Pb has a similar electronic structure with the latter, and can be used a modifier to enhance the contribution of covalent bonding.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Lead-Free Piezoelectric Materials»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Lead-Free Piezoelectric Materials» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Lead-Free Piezoelectric Materials» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.