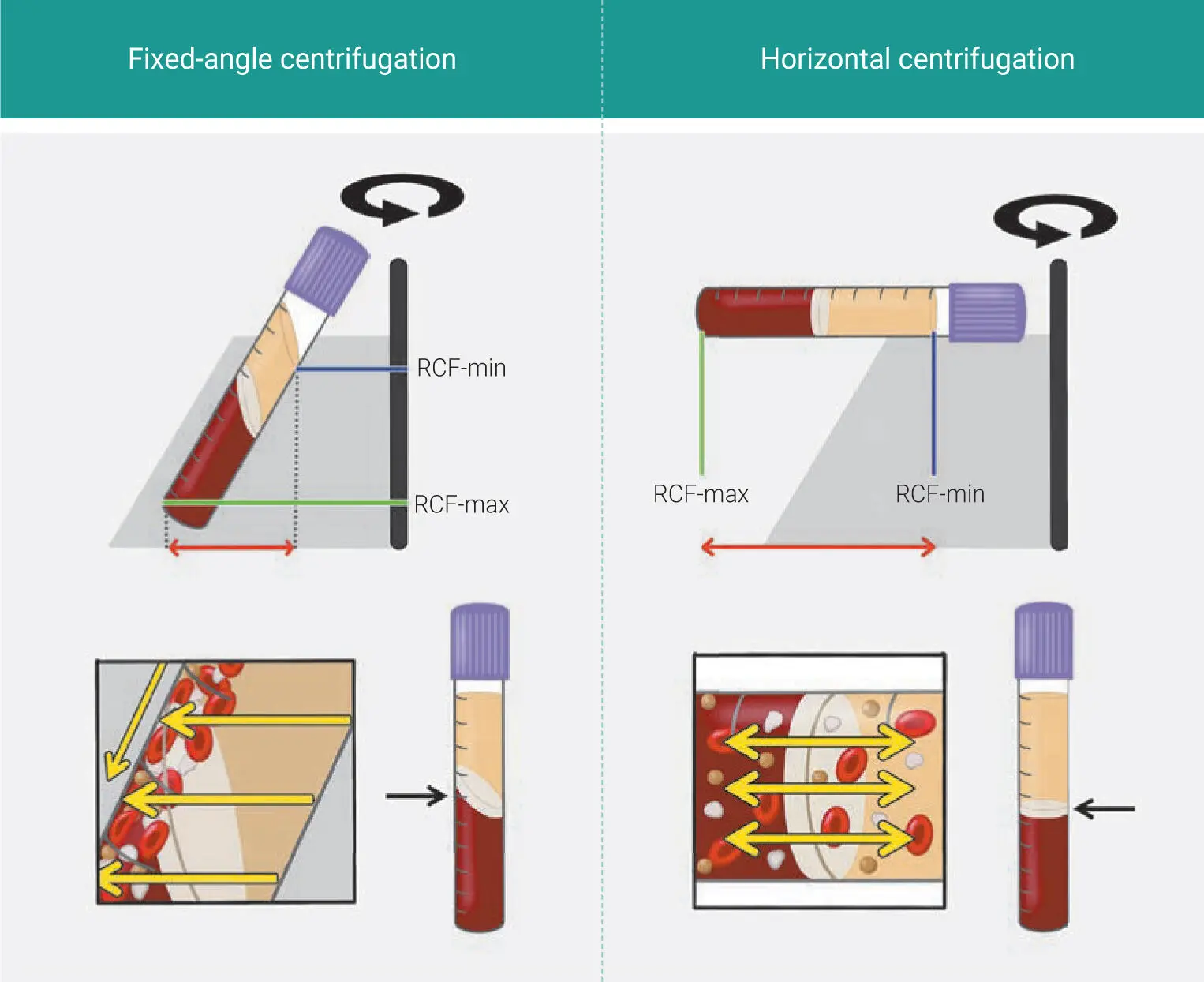

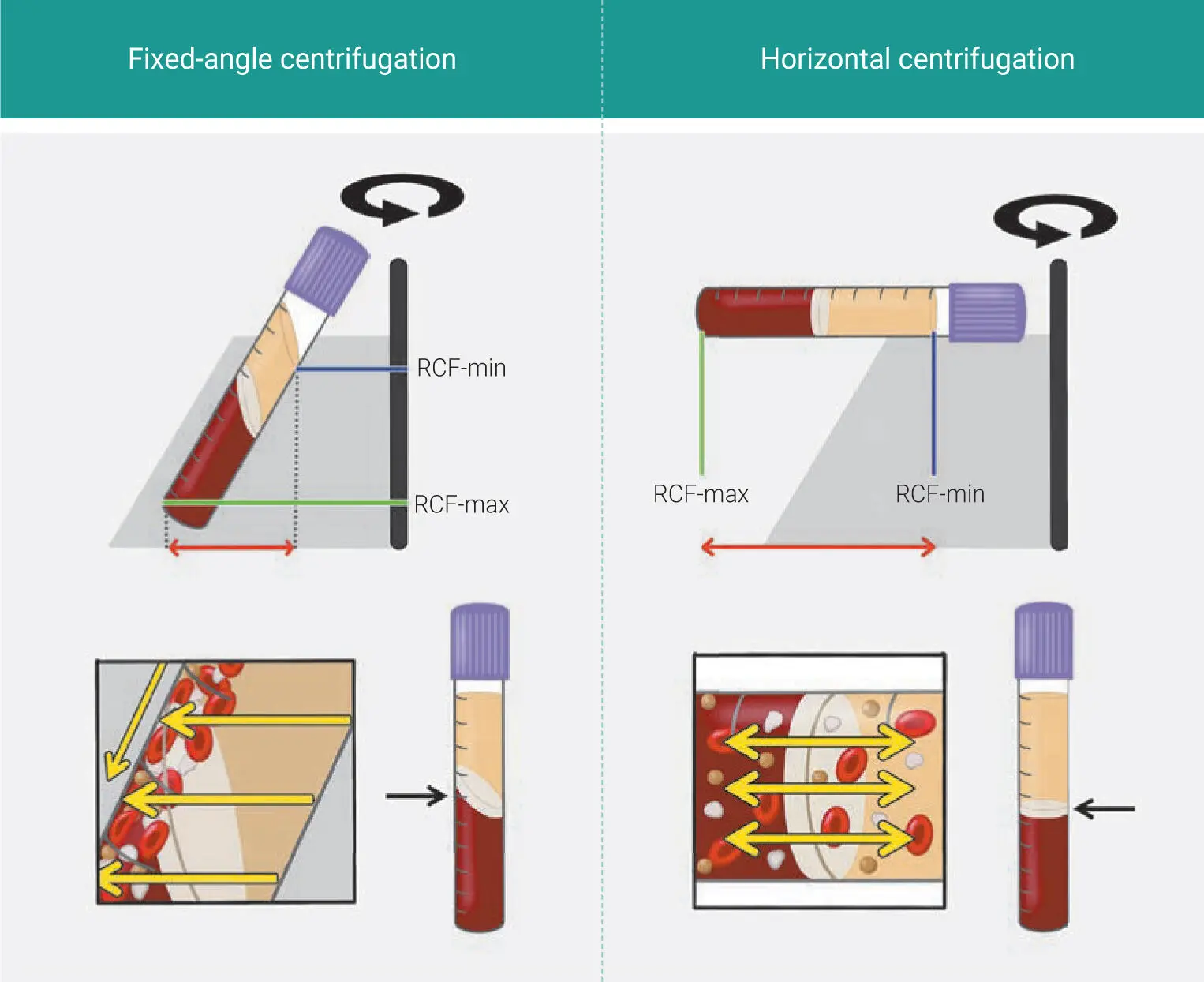

Fig 1-9Illustrations comparing fixed-angle and horizontal centrifuges. With horizontal centrifugation, a greater separation of blood layers based on density is achieved owing to the greater difference in RCF-min and RCF-max. Following centrifugation on fixed-angle centrifuges, blood layers do not separate evenly, and as a result, an angled blood separation is observed. In contrast, horizontal centrifugation produces even separation. Owing to the large RCF values (~200g–700g), the cells are pushed toward the outside and downward. On a fixed-angle centrifuge, cells are pushed toward the back of centrifugation tubes and then downward/upward based on cell density. These g-forces produce additional shear stress on cells as they separate based on density along the back walls of centrifugation tubes. In contrast, horizontal centrifugation allows for the free movement of cells to separate into their appropriate layers based on density, allowing for better cell separation as well as less trauma/shear stress on cells. (Modified from Miron et al. 41)

Fig 1-10Visual representation of layer separation following either L-PRF or H-PRF protocols. L-PRF clots are prepared with a sloped shape, and multiple red dots are often observed on the distal surface of PRF tubes, while H-PRF results in horizontal layer separation between the upper plasma and lower red corpuscle layer.

Furthermore, by utilizing a novel method to quantify cell types found in PRF, it was possible to substantially improve standard i-PRF protocols that favored only a 1.5- to 3-fold increase in platelets and leukocytes. Noteworthy is that several research groups began to show that the final concentration of platelets was only marginally improved in i-PRF when compared to standard baseline values of whole blood. 41,42In addition, significant modifications to PRF centrifugation protocols have further been developed, demonstrating the ability to improve standard i-PRF protocols toward liquid formulations that are significantly more concentrated (C-PRF) with over 10- to 15-times greater concentrations of platelets and leukocytes when compared to i-PRF (see chapters 2and 3). Today, C-PRF has been established as the most highly concentrated PRF protocol described in the literature.

Snapshot of H-PRF and C-PRF

Horizontal centrifugation leads to up to a four-times greater accumulation of platelets and leukocytes when compared to fixed-angle centrifugation systems commonly utilized to produce L-PRF and A-PRF.

Cells accumulate evenly when PRF is produced via horizontal centrifugation as opposed to along the back distal surface of PRF tubes on fixed-angle centrifuges.

Standard i-PRF can be further improved with horizontal centrifugation.

Conclusion

Platelet concentrates have seen a wide and steady increase in popularity since they were launched more than two decades ago. While initial concepts launched in the 1990s led to the working name platelet-rich plasma , subsequent years and discoveries have focused more specifically on their anticoagulant removal (ie, PRF). Several recent improvements in centrifugation protocols, including the low-speed centrifugation concept and horizontal centri-fugation, have led to increased concentrations of GFs and better healing potential. Both solid-PRF as well as liquid-based formulations now exist, with an array of clinical possibilities created based on the ability to accumulate supraphysiologic doses of platelets and blood-derived GFs. Future strategies to further improve PRF formulations and protocols are continuously being investigated to additionally improve clinical practice utilizing this technology.

References

1.Anfossi G, Trovati M, Mularoni E, Massucco P, Calcamuggi G, Emanuelli G. Influence of propranolol on platelet aggregation and thromboxane B 2production from platelet-rich plasma and whole blood. Prostaglandins Leukot Essent Fatty Acids 1989;36:1–7.

2.Fijnheer R, Pietersz RN, de Korte D, et al. Platelet activation during preparation of platelet concentrates: A comparison of the platelet-rich plasma and the buffy coat methods. Transfusion 1990;30:634–638.

3.Coury AJ. Expediting the transition from replacement medicine to tissue engineering. Regen Biomater 2016;3:111–113.

4.Dai R, Wang Z, Samanipour R, Koo KI, Kim K. Adipose-derived stem cells for tissue engineering and regenerative medicine applications. Stem Cells Int 2016;2016:6737345.

5.Rouwkema J, Khademhosseini A. Vascularization and angiogenesis in tissue engineering: Beyond creating static networks. Trends Biotechnol 2016;34:733–745.

6.Zhu W, Ma X, Gou M, Mei D, Zhang K, Chen S. 3D printing of functional biomaterials for tissue engineering. Curr Opin Biotechnol 2016;40:103–112.

7.Upputuri PK, Sivasubramanian K, Mark CS, Pramanik M. Recent developments in vascular imaging techniques in tissue engineering and regenerative medicine. Biomed Res Int 2015;2015:783983.

8.Gosain A, DiPietro LA. Aging and wound healing. World J Surg 2004;28:321–326.

9.Eming SA, Brachvogel B, Odorisio T, Koch M. Regulation of angiogenesis: Wound healing as a model. Prog Histochem Cytochem 2007;42:115–170.

10.Eming SA, Kaufmann J, Lohrer R, Krieg T. Chronic wounds: Novel approaches in research and therapy [in German]. Hautarzt 2007;58:939–944.

11.Miron RJ, Bosshardt DD. OsteoMacs: Key players around bone biomaterials. Biomaterials 2016;82:1–19.

12.de Vries RA, de Bruin M, Marx JJ, Hart HC, Van de Wiel A. Viability of platelets collected by apheresis versus the platelet-rich plasma technique: A direct comparison. Transfus Sci 1993;14:391–398.

13.Whitman DH, Berry RL, Green DM. Platelet gel: An autologous alternative to fibrin glue with applications in oral and maxillofacial surgery. J Oral Maxillofac Surgery 1997;55:1294–1299.

14.Marx RE, Carlson ER, Eichstaedt RM, Schimmele SR, Strauss JE, Georgeff KR. Platelet-rich plasma: Growth factor enhancement for bone grafts. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endodontol 1998;85:638–646.

15.Jameson C. Autologous platelet concentrate for the production of platelet gel. Lab Med 2007;38:39–42.

16.Marx RE. Platelet-rich plasma: Evidence to support its use. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2004;62:489–496.

17.Anitua E, Prado R, Troya M, et al. Implementation of a more physiological plasma rich in growth factor (PRGF) protocol: Anticoagulant removal and reduction in activator concentration. Platelets 2016;27:459–466.

18.Abd El Raouf M, Wang X, Miusi S, et al. Injectable-platelet rich fibrin using the low speed centrifugation concept improves cartilage regeneration when compared to platelet-rich plasma. Platelets 2019;30:213–221.

19.Kobayashi E, Fluckiger L, Fujioka-Kobayashi M, et al. Comparative release of growth factors from PRP, PRF, and advanced-PRF. Clin Oral Investig 2016;20:2353–2360.

20.Miron RJ, Fujioka-Kobayashi M, Hernandez M, et al. Injectable platelet rich fibrin (i-PRF): Opportunities in regenerative dentistry? Clin Oral Investig 2017;21:2619–2627.

21.Wang X, Zhang Y, Choukroun J, Ghanaati S, Miron RJ. Effects of an injectable platelet-rich fibrin on osteoblast behavior and bone tissue formation in comparison to platelet-rich plasma. Platelets 2018;29:48–55.

22.Lucarelli E, Beretta R, Dozza B, et al. A recently developed bifacial platelet-rich fibrin matrix. Eur Cell Mater 2010;20:13–23.

23.Saluja H, Dehane V, Mahindra U. Platelet-rich fibrin: A second generation platelet concentrate and a new friend of oral and maxillofacial surgeons. Ann Maxillofac Surg 2011;1:53–57.

Читать дальше