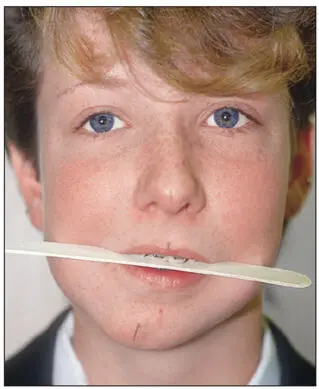

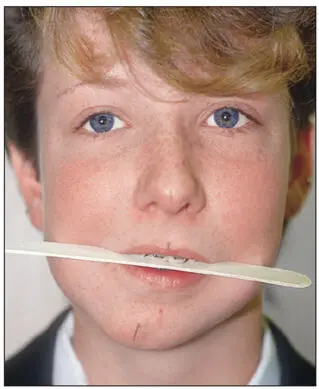

1 ...8 9 10 12 13 14 ...26 In faces with asymmetry involving the mandible, it is critical to note the midline of the chin and its relation to the mandibular dental midline. The chin is evaluated for symmetry, vertical relation, and shape. The cant of the occlusal plane is evaluated, especially in individuals with facial asymmetry, by asking the patient to bite on a wooden spatula and then relating the occlusal plane to the interpupillary line (Fig 2-20). The maxillary dental arch level (between the maxillary canine tips) must be distinguished from the mandibular dental arch level (between the mandibular canine tips). However, with this assessment it is necessary to make sure that the orbits are on a horizontal plane because there may be an orbital deformity influencing this observation. Patients who present with facial asymmetry and a cant in the occlusal plane will require an anteroposterior cephalometric radiograph for further analysis.

Fig 2-20The cant in the occlusal plane can be evaluated in relation to the interpupillary line by asking the patient to bite on a wooden spatula. During this assessment, make sure that the interpupillary line is parallel to the floor.

The amount of gingiva exposed during smiling is also noted. The ideal tooth exposure during smiling is the full tooth crown to 2 mm of gingiva, which occurs in females more often than males. When examining the smile, it should be kept in mind that the amount of tooth exposure is influenced by (1) the vertical length of the maxilla, (2) lip length, (3) maxillary incisor crown length, (4) amount of lip action with smile, and (5) shape of Cupid’s bow of the lip.

Surgical superior repositioning of the maxilla is indicated only when excessive gingival exposure is found in combination with an increased interlabial gap, increased maxillary incisor exposure, and increased vertical height of the lower third of the face. The amount of surgical superior repositioning will be dictated by the amount of tooth exposure, lip length, crown length, and age and sex of the patient. Keep in mind that superior repositioning of the maxilla will tend to shorten the upper lip. The upper lip will lengthen with age, especially in males. If necessary, surgical repositioning should err on the long side because overcorrection gives the patient a toothless and aged look.

One should never plan treatment based on the smile pattern. For example, an individual may exhibit a normal maxillary tooth–lip relationship (1 to 4 mm) that increases during smiling to expose up to 7 mm of gingiva (“gummy smile”). If superior repositioning is planned according to the amount of gingiva exposed during smiling, the maxilla will need to be superiorly repositioned by 6 mm to establish the ideal full tooth exposure. However, this will result in no tooth exposure and a toothless look in repose.

Lips

The lips are extremely critical to overall esthetics. Lip symmetry should be evaluated; if asymmetry exists, its etiology should be determined (eg, cleft lip, facial nerve dysfunction, underlying dentoskeletal asymmetry, scarring caused by previous trauma, or congenital unilateral microsomia or macrosomia).

The lower lip generally exhibits 25% more vermilion than the upper lip, and the lips should be 0 to 3 mm apart in repose. An increased overjet will result in an everted lower lip and excessive vermilion exposure due to the effect of the maxillary incisors on the lip. There are specific racial differences in lip thickness and shape that one must bear in mind for the purposes of treatment planning. To accurately evaluate the maxillary incisor–lip relationship in patients with closed bites, the lips should be relaxed and the jaws moved apart until the lips are slightly parted (closed bites may be the result of maxillary vertical deficiency or severe deep bites). Accentuation of Cupid’s bow of the upper lip may lead to exposure of the maxillary central incisors only. This exposure of the maxillary central incisors will not be evident on a lateral cephalometric radiograph because only the central incisors can be seen. Therefore, the amount of superior repositioning of the maxilla in patients with vertical maxillary excess should be assessed clinically and not radiographically.

Nose

Although the nose has not always been considered part of orthognathic correction, it comprises an important aspect of the overall facial esthetics, and the form and function of the nose can be affected by orthognathic surgery. Many orthognathic surgeons also perform rhinoplasty as part of overall dentofacial correction. In many instances, nasal reconstruction may be part of the orthognathic treatment plan; sometimes, rhinoplasty and orthognathic surgery can be performed simultaneously. Control of the nasal form should also be considered, especially in patients requiring superior repositioning and/or advancement of the maxilla (see page 292.)

The functional and esthetic nasal evaluation should be included in the examination of the orthognathic patient. An intranasal examination should be performed to identify a possible existing deviated nasal septum, hypertrophied turbinates, or nasal polyps. Esthetic concerns should be noted, and the nose should be evaluated from a frontal and profile view.

A discussion of detailed esthetic parameters of the nose is beyond the scope of this text. However, important esthetic factors to consider are the width of the nasal base, the distance from the base of the nose to the anterior extent of the nares, and from the anterior aspect of the nares to the tip of the nose. The prominence of the dorsum, the shape of the nasal tip, and the acuteness of the supratip break must also be considered in relation to the intended orthognathic surgery and the physical and/or relative esthetic effects surgery may have on these structures. The length of the columella and the nasolabial angle as well as the projection and shape of the nares should be considered; these aspects may be negatively affected by maxillary surgery.

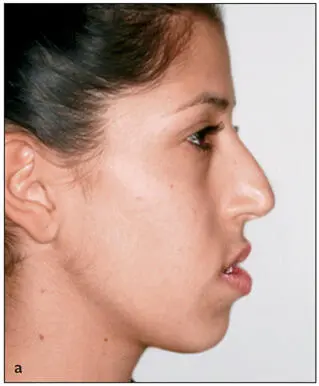

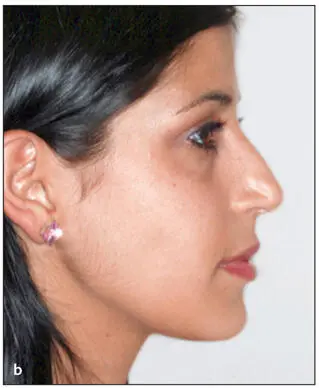

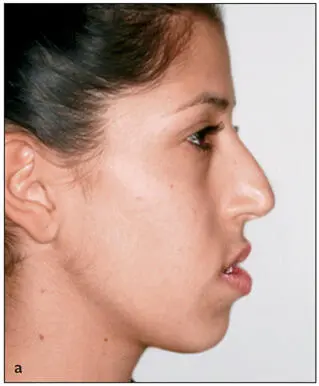

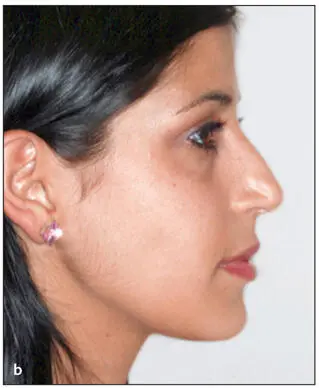

Because orthognathic surgery can have a relative and anatomical effect on nasal form and esthetics, simulta-neous rhinoplasty and orthognathic surgery should be limited to small corrections to the nasal dorsum only. Formal rhinoplasty should be deferred to a second procedure. Figure 2-21 demonstrates the profound relative change of the nose following orthognathic surgical correction of a Class III malocclusion.

Fig 2-21Corrective facial changes following orthognathic surgery may have a profound relative and/or anatomical effect on the nose. (a) Preoperative view showing a nose that appears large with a prominent dorsum. (b) The nose appears to have a normal shape and form following correction of a Class III occlusion by superior repositioning of the maxilla via a Le Fort I osteotomy, mandibular setback by means of a bilateral sagittal split osteotomy, and advancement genioplasty.

Although the face is divided into equal thirds to simplify clinical examinations and for schematic descriptive purposes, an orthognathic surgical procedure may affect the soft tissue in one or more of these thirds. Ferretti and Reyneke described the division of the face from the frontal view into five areas of surgical influence (Fig 2-22).

Читать дальше