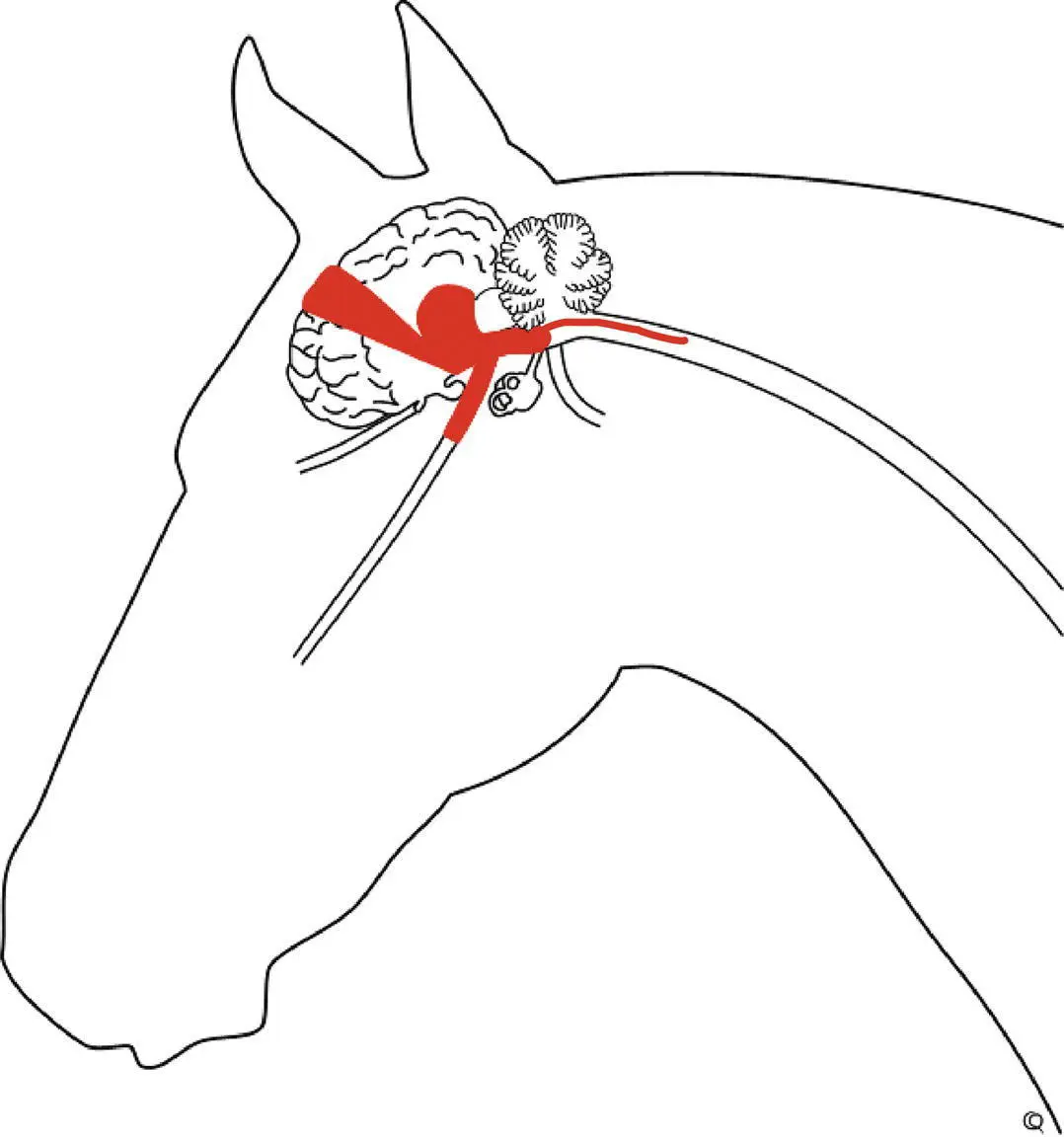

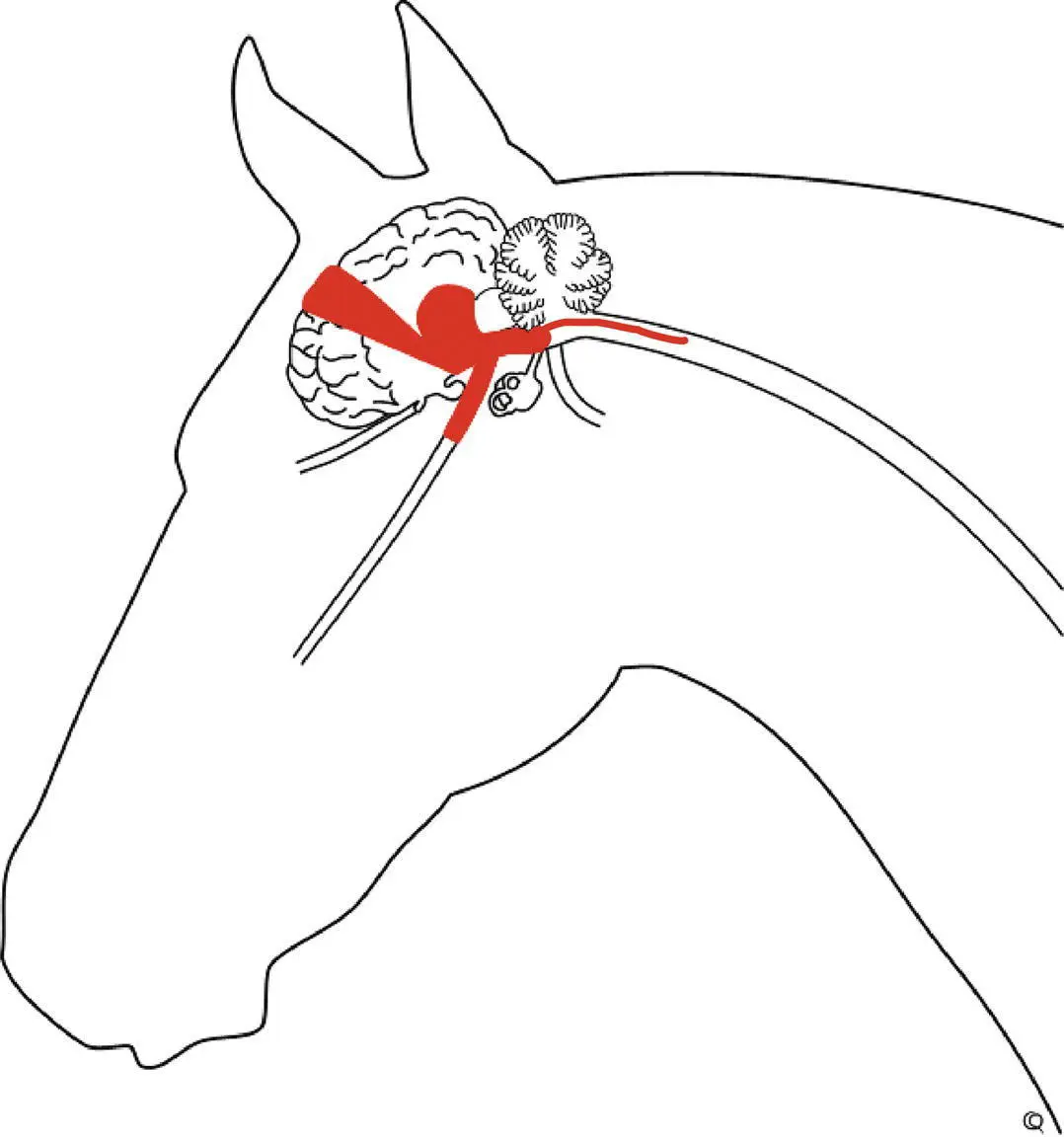

Many encephalitides that may involve the pontomedullary region where the motor nucleus of the trigeminal nerve resides can effect the syndrome of mandibular muscle atrophy. Degrees of weakness, ataxia, obtundation, and other cranial nerve palsies are usually evident. On the American continents, a syndrome of unilateral and much less commonly bilateral atrophy of mandibular muscles is seen in horses suffering from S. neurona and other protozoal myeloencephalitides, sometimes with no other evidence of brainstem disease. Thus, this mimics peripheral CN Vm neuropathy ( Figures 12.4and 12.5). Ruminants suffering from listeriosis have also been seen with brainstem disease to include unilateral and sometimes bilateral mandibular muscle atrophy, some having a flaccid mandible with the latter. 5–8

Marked masseter, temporalis, and pterygoid muscle atrophy also results in slight degrees of enophthalmos and drooping of the upper eyelid, at least in cattle 9,10and horses. This appears to be caused by the loss of muscle mass behind the globe, which is signaled by sinking of the retrobulbar tissues in the supraorbital fossa. Non‐neurologic causes of oral dysphagia, such as temporomandibular disorders and particularly dental problems, can be associated with atrophy of the muscles of mastication that at times can be very asymmetric ( Figure 12.6).

Figure 12.4 In the absence of other neurologic abnormalities or other evidence of a lesion in the region of the rostral base of cranium, atrophy of the muscles of mastication on one side in a horse from the Americas is very likely to be caused by S. neurona encephalitis as was the case here. Neoplasia and trauma to the basilar region rostral to the guttural pouch also have produced such a syndrome of atrophy of the masseter, temporalis, pterygoid, and distal digastricus muscles innervated by the trigeminal nerve.

To be differentiated from this problem is the trismus seen with tetanus and the dystonia of jaw and tongue muscles seen with equine nigropallidal encephalomalacia, among other orthopedic and neurologic disorders.

Figure 12.5 This horse was also suffering from S. neurona encephalitis partly involving left and right motor nuclei of the trigeminal nerves in the pontomedullary region. It had normal movement of the facial muscles, lips, and tongue but could not close the jaw (A). Drinking was achieved by lapping like a dog (B).

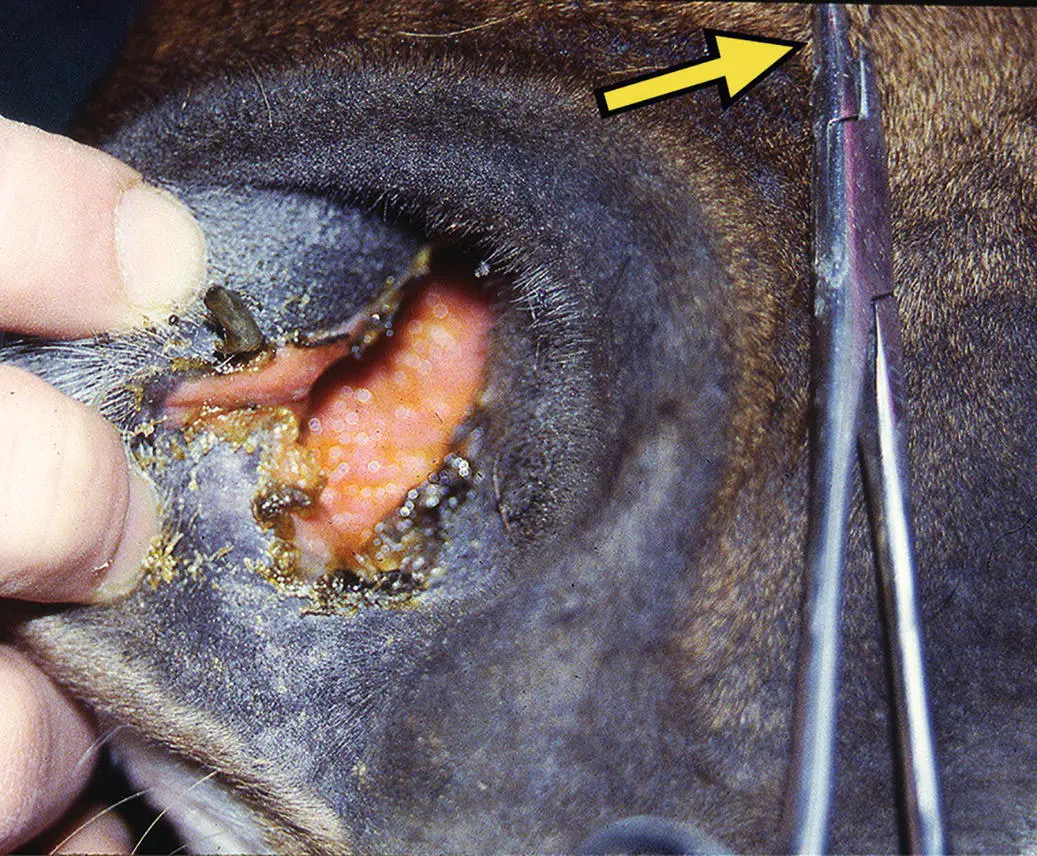

Figure 12.6 Asymmetric temporalis (and masseter and pterygoid) muscle atrophy (A) can be associated with severe dental problems as seen in this teenaged Thoroughbred with a deep supraorbital fossa on the right side (yellow arrow) compared with that on the left side (white arrow). Long fibers of chewed forage were present in the feces (B) associated with the oral dysphagia displayed by the horse. All signs were resolved with appropriate dental care.

1 1 Pearson EG, Snyder SP and Saulez MN. Masseter myodegeneration as a cause of trismus or dysphagia in adult horses. Vet Rec 2005; 156(20): 642–646.

2 2 Conwell R. Hyperlipaemia in a pregnant mare with suspected masseter myodegeneration. Vet Rec 2010; 166(4): 116–117.

3 3 Step DL, Divers TJ, Cooper B, et al. Severe masseter myonecrosis in a horse. J Am Vet Med Assoc 1991; 198(1): 117–119.

4 4 Aharonson‐Raz K, Milgram J, Chai O and Sutton GA. Fibrosis of the masseter leading to trismus and dysphagia in a mare. Vet Rec 2009; 164(19): 597–608.

5 5 Schweizer G, Ehrensperger F, Torgerson PR and Braun U. Clinical findings and treatment of 94 cattle presumptively diagnosed with listeriosis. Vet Rec 2006; 158(17): 588–592.

6 6 Braun U, Stehle C and Ehrensperger F. Clinical findings and treatment of listeriosis in 67 sheep and goats. Vet Rec 2002; 150(2): 38–42.

7 7 Rebhun WC and deLahunta A. Diagnosis and treatment of bovine listeriosis. J Am Vet Med Assoc 1982; 180(4): 395–408.

8 8 Barlow RM and McGorum B. Ovine listerial encephalitis: analysis, hypothesis and synthesis. Vet Rec 1985; 116(9): 233–236.

9 9 Divers TJ and Peek SF. Rebhun's Diseases of Dairy Cattle. Saunders Elsevier, Philadelphia, PA. 2008.

10 10 Rebhun WC. Diseases of the bovine orbit and globe. J Am Vet Med Assoc 1979; 175(2): 171–175.

13 Decreased and Increased facial sensation

Many animals, mentally obtunded because of marked systemic illness and particularly severe brain disease, are slow to respond to noxious stimuli anywhere on the body, including the face. The problem of decreased facial sensation is identified when the degree of hypalgesia detected is greater than that to be expected by any accompanying somnolent or moribund state or is demonstrably asymmetric.

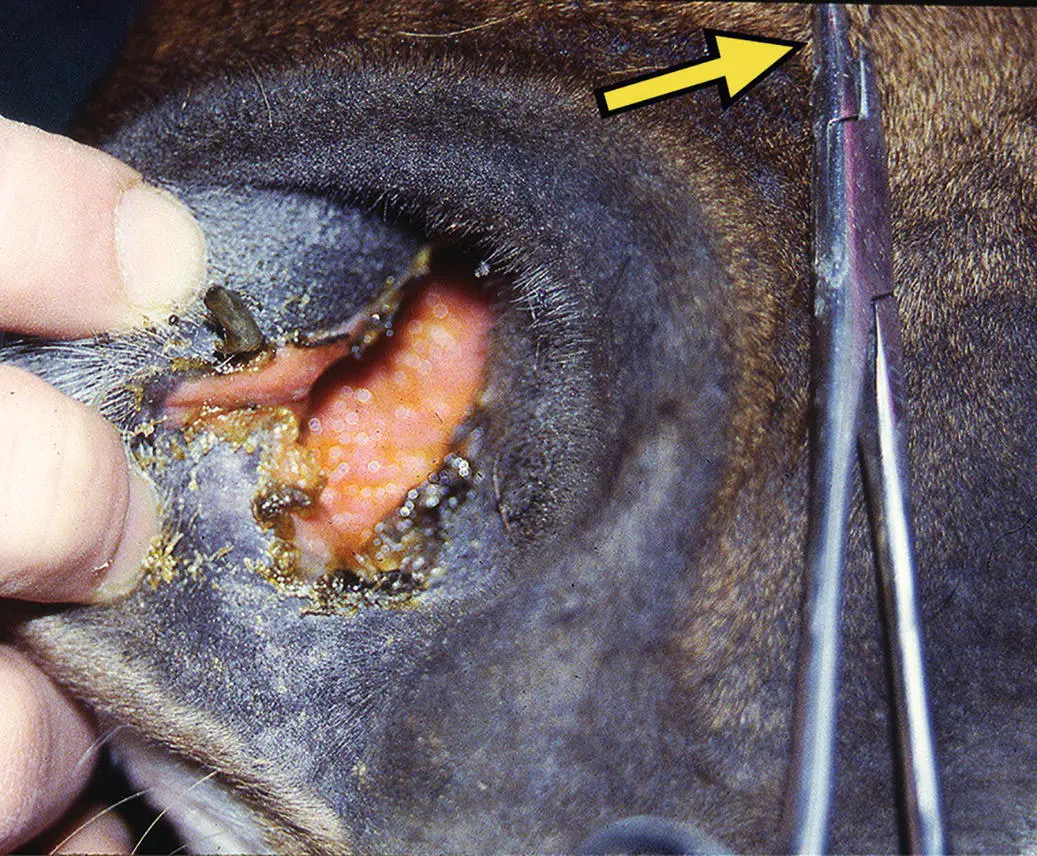

In defining this problem, care must be taken to distinguish facial hyporeflexia from facial hypalgesia—and these signs can occur together. The facial reflex (CN V sensory →CN VII motor) can be poorly functional with lesions involving the sensory trigeminal nerve, ganglion or nucleus, or the facial motor nucleus or nerve. With lesions involving the sensory branches of the trigeminal nerve, these facial reflexes will not function. Degrees of facial hypalgesia or analgesia also occur and the animal does not pull its head away from the noxious facial stimulus, for example in a cow that had an ocular squamous cell carcinoma invading the trigeminal nerve resulting in facial analgesia. 1

Sensation from at least the rostral third of the tongue of horses is mediated via fibers in the mandibular nerve and that has been inadvertently sectioned during surgical debulking of intermandibular tumors, resulting in analgesia and areflexia from the ipsilateral rostral circa 10 cm of the tongue. Expansile retrobulbar tumors including lymphosarcoma, melanoma, squamous cell carcinoma, and parotid adenocarcinoma have caused facial hypalgesia, usually with other overt evidence of face and eye lesions. 2,3Partial facial analgesia resulting from trauma to single branches of CN Vs is not common and is usually associated with trauma to the face, nasal region, and sinuses. Because distal portions of sensory trigeminal nerves are distributed with branches from autonomic nerves, processes such as perineuritis that affect distal nerves may result in signs of autonomic denervation. For example, trigeminal innervation of the nasal membranes includes parasympathetic branches of CN VII, thus resulting in rhinitis sicca when these nerves are damaged ( Figure 13.1). A similar involvement of oculomotor branches to the eyeball that are confluent with the ophthalmic branch of CN V may also result in poor pupillary constrictor function ( Figure 13.2).

Figure 13.1 Facial analgesia is evident in the bright and alert horse shown here, by the needle holders clamped on the distal face (arrow). There was a cranial—believed immune‐associated—polyneuritis particularly involving the trigeminal nerves, with bilateral facial and rostral nasal analgesia. The presence of severe rhinitis sicca as also shown was unusual. In the right clinical setting, this sign is regarded as almost pathognomonic for equine dysautonomia, but this horse had no other signs of enteric or autonomic nervous dysfunction. As is the case often with polyneuritis equi, the trigeminal neuritis was accompanied by a prominent perineuritis. Also, the neuritis involved not just proximal cranial nerves but spread along the distal branches. It was believed that the more distal perineuritis involving the maxillary nerve also involved the autonomic fibers innervating the nasal membranes, mimicking the rhinitis sicca seen with grass sickness.

Читать дальше