Twice earlier, I had experienced similar mortal fear in a tiny Fiat. The first time occurred in the winter of ’77, when Maria-Pia Canaponi, a young Florentine, drove me and a friend from the hilltop town of Fiesole down to Florence, hidden in the misty and shadowy depths of the Arno valley. As I recalled over the years, she didn’t so much as drive as allow the car to simply fall downhill, even though the wheels did touch the ground here and there on a hairpin curve, but more like the soles of a mountaineer’s boots graze the side of a cliff as he rappels down a rock face.

The other death-defying Fiat, also somewhere in the mid-seventies, bored its way through the hellish Parisian morning traffic. At the wheel was a local woman, her hat crumpled by the city’s night life. She was trying to impress me (in back) and her girlfriend up front by ignoring red lights or, at the very least, by blindly changing lanes with her brim pulled down over her eyes. Arriving at her house in a suburb of Paris, sheer terror and heart palpitations made it impossible for me to perform up to snuff.

But now the claustrophobic tin can was jostling an unborn life. The midwife manoeuvred her car down the Cornelis Krusemanstraat towards the Harlemmercircuit — and that is where I must have lost track of where we were, distracted as I was by Miriam’s birthing pains. I wasn’t paying attention, and Miriam even less, so neither of us noticed that the midwife had turned right onto the Amstelveenseweg towards the Zeilstraat instead of taking the roundabout to the other leg of the Amstelveenseweg that led to the VU hospital.

Yes, I do recall my impatience at the open drawbridge over the Schinkel, raised like an unbreachable rampart, but it still did not occur to me that our rolling maternity bed was heading the wrong way. Miriam herself realised the mistake only when we reached the hospital. Once inside, the midwife and I helped her into a wheelchair. As we wheeled her through the foyer towards the lift, Miriam whimpered: ‘This isn’t the VU … I was supposed to deliver at the VU.’

‘Oh, sorry, hon, sorry … sorry,’ cried the midwife. ‘My fault entirely. I must have looked at the wrong form this morning … Oh, how awful. Well, there’s no turning back now.’

She had taken us to Slotervaart Hospital.

3

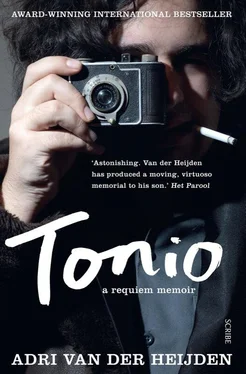

The two police officers turned us over to a small group of nurses in a reception area at the top of a short set of stairs. I can’t remember which of the four or five of them handed me Tonio’s wallet. The grey billfold with snap fastener lay heavily in my hand: its change pocket was laden with coins. I imagined that it still retained some of his body heat — from his thigh, his buttocks, or his breast, wherever he had it at the moment of …

Stuck to the back of the wallet was a self-adhesive, computer-printed sticker bearing his name, a few series of digits and today’s date (how new and nearby everything was). In our absence, they were already busy transforming him into a series of numbers.

The two officers took their leave with a handshake, and wished us ‘ sterkte ’ — courage, strength. I took the opportunity to study their uniforms one last time. Once this was all behind us and we knew how long Tonio’s recovery would take, I could — no matter how shaken and depressed — return to my writing table and resume work on the police novel. I had pinned up a photo of a female police chief in standard uniform. Now I had been given extra information regarding how a rank-and-file policewoman looked in warm weather.

The policeman handed me a card from the Serious Traffic Accident Unit on the James Wattstraat, where I could request a more complete report on the collision. I had only to ask for the staff member whose name he’d written in with a ballpoint pen.

The officers raised a hand as they descended the stairs, heading towards the revolving door and their van, parked in the sun. Miriam and I followed the nurses to the Intensive Care Unit (Intensive Care, which was different than the Emergency Room. Ambulance, ER, ICU, OR: Tonio’s body had made a speedy series of promotions.) On the way, one of them apologised for the fact that we had been informed so late.

‘His wallet was full of cards, but we couldn’t come up with an address right away for … for his parents. At moments like that, a life-threatening situation, we have other priorities. Saving a life always comes first.’

Life-threatening situation . A doctor was waiting for us at the junction of two corridors. We were told that Tonio had been on the operating table for ‘hours’ (it was approaching ten o’clock) and was still in a critical condition.

‘The traumatologist will be out shortly to give you an update.’

I gathered we were now in the ICU. A young nurse, blonde and blue-eyed and as fresh as the morning, led us to a small waiting room and offered us coffee.

‘Just some water,’ said Miriam, who had already sidled against me on the three-seat sofa.

‘Coffee for me, please,’ I said.

The nurse left the room, leaving the door open. Above the doorway was a large kitchen clock: ten past ten.

‘Ugh, no coffee,’ Miriam said. ‘It reminds me of when …’

She reached for her forehead and cried, sputtering slightly. She didn’t need to finish her sentence. I knew she was referring to that June morning in ’88, when we mistakenly ended up at the Slotervaart maternity ward, and Miriam had gone into hysterics over my coffee breath.

I opened Tonio’s wallet. The billfold section contained nothing but a five-euro note. The coins, all told, probably added up to a sizeable amount.

A year earlier, in August, after the premiere of Het leven uit een dag , I had studied his bar behaviour during the reception at De Kring. Tonio and Marianne had retired to a dark corner somewhere alongside the dance floor where the crew were swinging to the house music, and whenever he went to fetch drinks for himself or the girl, he paid with a banknote and jammed the change into the pocket of his wallet (the very one I was now holding in my hands). Those slight tendencies towards disorderliness: I lamented them all the more because I exhibited them myself at his age, and long thereafter, and still had not managed to overcome them all. Continually confronted, in matters both minor and significant, with our similarities, I was forced to imagine myself as a twenty-one-year-old. It worried me. Not for myself, but for him.

‘If Tonio really is so much like me,’ I said to my brother, who sat next to me at the bar in De Kring, ‘then he’s got an uphill battle ahead of him.’

Frans, who knew me in my early twenties and even lived with me for a while, sputtered out a feeble denial just to be polite.

There were plenty of cards and passes, complete with address, in the pockets of Tonio’s wallet, so I suspected that there had indeed been more urgent matters than tracking down his parents.

‘Here’s an ID card from the Onze Lieve Vrouwe Gasthuis,’ I said to Miriam. ‘What would he have been doing there?’

‘Jaw surgeon,’ she said with a shrug of revulsion. ‘Wisdom teeth.’

The nurse came in with a tray, and arranged the Thermos cans, cups and glasses on the table. ‘The traumatologist will be in to see you shortly,’ she said as she was leaving. ‘If you need anything, just check the corridor, one of us will be there.’

4

Since being roused from bed, I had hardly spoken, except with Miriam, but every time I opened my mouth, first to the police officers and now to the nursing staff, I was painfully aware of the heavy odour of garlic on my breath. I didn’t smell it myself, but seeing as we hadn’t had breakfast yet I knew it rose straight from my gut. (This morning, when I went downstairs, the kitchen door on the first floor was open. Spread out on the bread board were four rolls, sliced and waiting to be buttered. Oranges alongside the juice squeezer. A still-life in the wake of bad tidings.)

Читать дальше