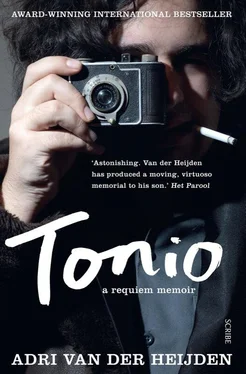

Tonio? We had a deal: he was free to use the entire house, except for the floor where my office was, because I was busy sorting through material, and there were stacks of handwritten, as-yet unnumbered sheets everywhere. I had a good look around. There was no evidence of them having taken photos here. No styrofoam sheets. No film roll wrappers in the wastebasket. No sign of the unwelcome rearranging to which photographers from newspapers and magazines so enjoyed subjecting one’s home.

Was I hoping for signs of an amorous interlude? The book about Dutch police precincts, a reference aid for my novel that I kept stuck between the two seat cushions of the chaise longue, was still in place.

I opened the balcony doors. The slats and planks that used to be Tonio’s old bunk bed lay precisely as our handyman René had left them, only a bit more grey-green after exposure to the snow and rain. To the right, an aluminium fire-escape ladder led up to the roof.

‘Minchen, when we came back from the park … did you raise the awning in my office?’

‘No, you must’ve done it yourself. I can’t do everything.’

I was none the wiser. I decided to ring Tonio about it — tonight, or else tomorrow. Not to scold him for having invaded my workspace, but … well, maybe I’d find out some details of his love life. My God, what an old busybody I was becoming.

The phone call went by the wayside. Soon … later, while he was recuperating, I’d ask. God knows how many hours we would have to spend at his bedside until he was himself again. There’d be enough time to talk. I would jabber him through it.

11

A critical condition: what is that, actually? Perhaps they were quick to call someone’s condition ‘critical’ so that if it did turn out badly for the patient after all, they’d be safeguarded against the vengeful indignation of the survivors.

I was reminded of my cousin Willy van der Heijden Jr., who was declared clinically dead after a motorcycle accident. Illusionist-joker that he was, he rose from the dead, and six weeks later returned to business as usual, which in his case meant low- to medium-grade criminality. So it could swing that way, too.

No, bad example. Not even a year later, he was on the run, artificial knee joints and all, from the police, and crashed himself just as dead as before by smashing his car into a tree: no headlights on an unlit road. This time he skipped the ‘clinically’ phase.

I remember my mother calling me up with the news. ‘A bad egg, that boy, but I had to let you know.’

While I was on the phone with her,I looked at the eighteen-month-old Tonio as he crawled across the rug, drooling from the exertion. No such thing would ever happen to him, I would see to that. With the upbringing I was going to give him, he would never have to flee from the police, let alone with his headlights off.

‘How’s Uncle Willy taking it?

‘He’s a wreck, of course. He’d put all his hopes into that boy. The neighbours said he wandered the streets the whole night with his dog. Talking out loud. Yelling.’

‘He might be dead already,’ Miriam moaned.

‘A critical condition,’ I said, ‘can mean anything. I’m sure they’re doing their best.’

‘He’s being operated on,’ the policeman said. ‘They’ve been busy for hours.’

Goddamn. That did sound critical.

CHAPTER THREE. Wrong hospital

1

The police van took several successive curves, which our speed made seem sharper than they were. I either nearly slid away from Miriam along the slick upholstery, or was thrust up against her with a sudden force, which evoked a gagging sound from her.

‘Sorry, baby.’

Three weeks shy of twenty-one years ago, we also embarked on a wild ride to a hospital, but in a much smaller vehicle: a Fiat Panda. Miriam had woken me at 4.00 a.m. with severe abdominal cramps.

‘Are you sure it’s your intestines?’

‘I haven’t been to the toilet all week.’

She held my hand. I could tell from her grip how much pain she was in, and how regularly the cramps came. She was trembling. We lay like this, in silence, for a good while.

That night, we had gone to bed arguing. Anticipating the increased washing needs, we had bought a washing machine a couple of days earlier. After the burly delivery men had left, their far-too-generous drink tip in hand, I noticed that the white casing was damaged. By the time I had got the manager of the appliance store on the line, my reserve of diplomacy was depleted: the jerks had screwed up, period. The same fellows returned later that day, now far less friendly, to exchange it. Only after they left did their revenge reveal itself. During the test run, the thing shuddered and stomped loose from the wall. Standing barefoot on the tile floor, I had no choice but to hop backwards away from the machine, lest its undoubtedly sharp bottom edge amputate my toes. While performing a life-saving jitterbug, I also had to find the off button in order to subdue the automatic monster.

Miriam was convinced that the delivery men had left the safety bolts in the drum on purpose. ‘You always over-tip, that’s why. Then they mess with you.’

It was approaching five-thirty. My hand was gradually becoming disjointed by Miriam’s constant squeezing. Her beautiful, smooth forehead, which seldom perspired, was now beaded with sweat. ‘This can’t be just a stomach ache,’ I said.

‘I’ll ring the midwife just to be on the safe side,’ Miriam said. She wasn’t due for another three-and-a-half weeks. The midwife had her explain in detail what exactly she felt. The call was brief. ‘She’s on her way. I might have to go to the hospital already.’

‘Minchen, your overnight bag … The folder says you have to have a bag packed and ready. We don’t have one.’

‘That’s just like you,’ she moaned, ‘to start whinging about an overnight bag at a time like this. I’ve got other things on my mind, you know.’

The stabs worsened. The midwife arrived, her face still lined with sleep, just after six. She put a rubber glove on her right hand and asked me to wait outside. I suppose I could have packed a small travel bag in the meantime, but just stood there inert in the hallway.

‘Now, honey,’ I overheard, ‘you’re dilating already.’

So they were contractions after all, and they were getting stronger. I helped Miriam into her bathrobe. ‘It’s more painful than I expected,’ she said.

The midwife’s Fiat Panda was double-parked downstairs in front of the house. Heavily pregnant, Miriam looked too big for the compact car, but she just fitted. With the midwife at the wheel and us in back, the Panda was more than full.

‘Help, my claustrophobia’s playing up,’ Miriam panted hotly in my ear.

The midwife turned left onto De Lairessestraat, where morning traffic, even this early, was already nervously picking up. The Fiat proceeded with little jerks — leaps, really — and Miriam whimpered.

‘Just get me to the VU,’ she whispered.

2

The van had a lot less traffic trouble now than the Fiat did back then. Morning rush-hour was usually not yet over at ten to ten, but this was Sunday. We drove past a tidily laid-out business park, out of which rose the terraced buildings of the Academic Medical Centre. Somewhere inside, amid the labyrinth of overlit corridors, masked surgeons were operating on Tonio.

If he was still alive.

Twenty-two years ago, just like now, Miriam sat to my left on the back seat of the Panda. Then, too, I hugged her tight, pressed her close to me, so that I felt every contraction pulse through my own body — well, on the surface, anyway, because I couldn’t really feel the pain. Miriam occasionally gave my sleeve a tug to indicate that I should loosen my grip, which did not absorb the contractions.

Читать дальше