Provide a basic understanding of ultrasound principles and common artifacts to maximize accurate image interpretation.

Provide a basic understanding of how common ultrasound artifacts are formed to avoid image misinterpretation of artifacts for abnormalities.

Artifacts of Attenuation: Strong Reflectors (Bone, Stone, Air)

Shadowing, “Clean” and “Dirty”

Clean shadows and dirty shadows result from strong reflectors (bone, stone, and air). We know from differences in acoustic impedance at soft tissue–air and soft tissue–bone (stone) interfaces that most of the sound waves will be reflected, albeit in different degrees ( Figures 3.1and 3.2A).

Bone or Stone Interface: Clean Shadowing

When the ultrasound wave strikes bone (and stone), most of the waves are reflected back so there will be an area of intense hyperechogenicity (whiteness) at the soft tissue–bone (stone) interface. Because the surface of bone is often smooth, there is little scattering or reverberation of the ultrasound wave and a nice, clear‐cut, anechoic (blackness) “clean shadow” is produced beyond the reflector (bone or stone) (see Figure 3.1).

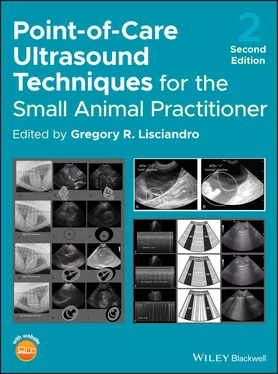

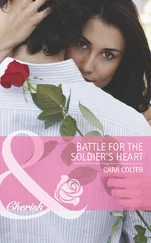

Figure 3.1. Dirty and clean shadowing. (A) "Dirty shadowing" created by air, a gas bubble within a fluid‐filled distended loop of small bowel. "Dirty shadowing" is generated because some ultrasound waves pass through the structure. Contrast the "dirty shadowing" with the "clean shadowing" of the cystourolith (urinary bladder stone) in (B) in which all ultrasound waves are reflected back to the transducer. (B) "Clean shadowing." The smooth surface of the cystourolith (urinary bladder stone) generates the "clean shadowing" typical of bone or stone with a hyperechoic (bright white) reflective surface in the near field, completely blocking all echoes and thus resulting in an anechoic (dark or black) shadow extending from it through the far‐field. In (C) and (D), the images have arrows (←) pointing out the artifact.

Source: Courtesy of Dr Sarah Young, Echo Service for Pets, Ojai, California.

Air Interface: Dirty Shadowing

On the other hand, soft tissue–air interfaces are more variable in their degree of reflection, with some of the ultrasound waves incompletely moving through the air‐filled structure, unlike the complete reflection at bone (or stone). Thus, reverberations occur distal to the air interface, creating a “dirty shadow” (Penninck 2002) (see Figure 3.1).

Artifacts of Attenuation: Fluid‐Filled Structures

Edge Shadowing: Fluid‐Filled Structures

When the ultrasound waves strike the edge of a fluid‐filled structure with a curved surface (its wall), such as the stomach wall, urinary bladder, gallbladder, eye, or cyst, ultrasound waves are reflected to a small degree and these reflected sound waves therefore do not return to the transducer. As a result, a thin hypoechoic (darker) to anechoic (black) area lateral and distal to the edge of the curved structure is formed. For example, the novice may mistake this artifact for a “rent” in the urinary bladder wall when in fact it is an artifact created by the ultrasound machine (Nyland et al. 2002) (see Figure 3.2).

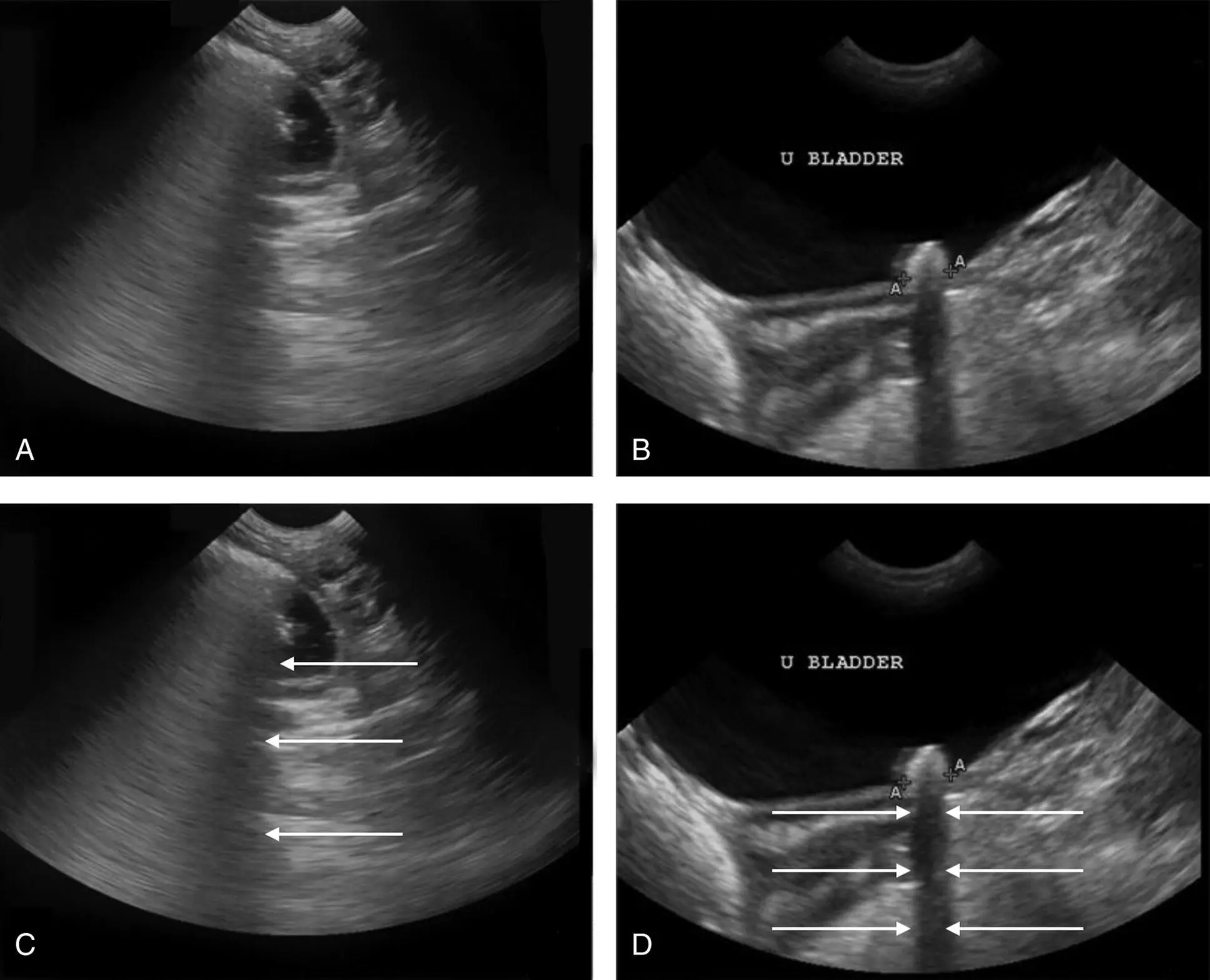

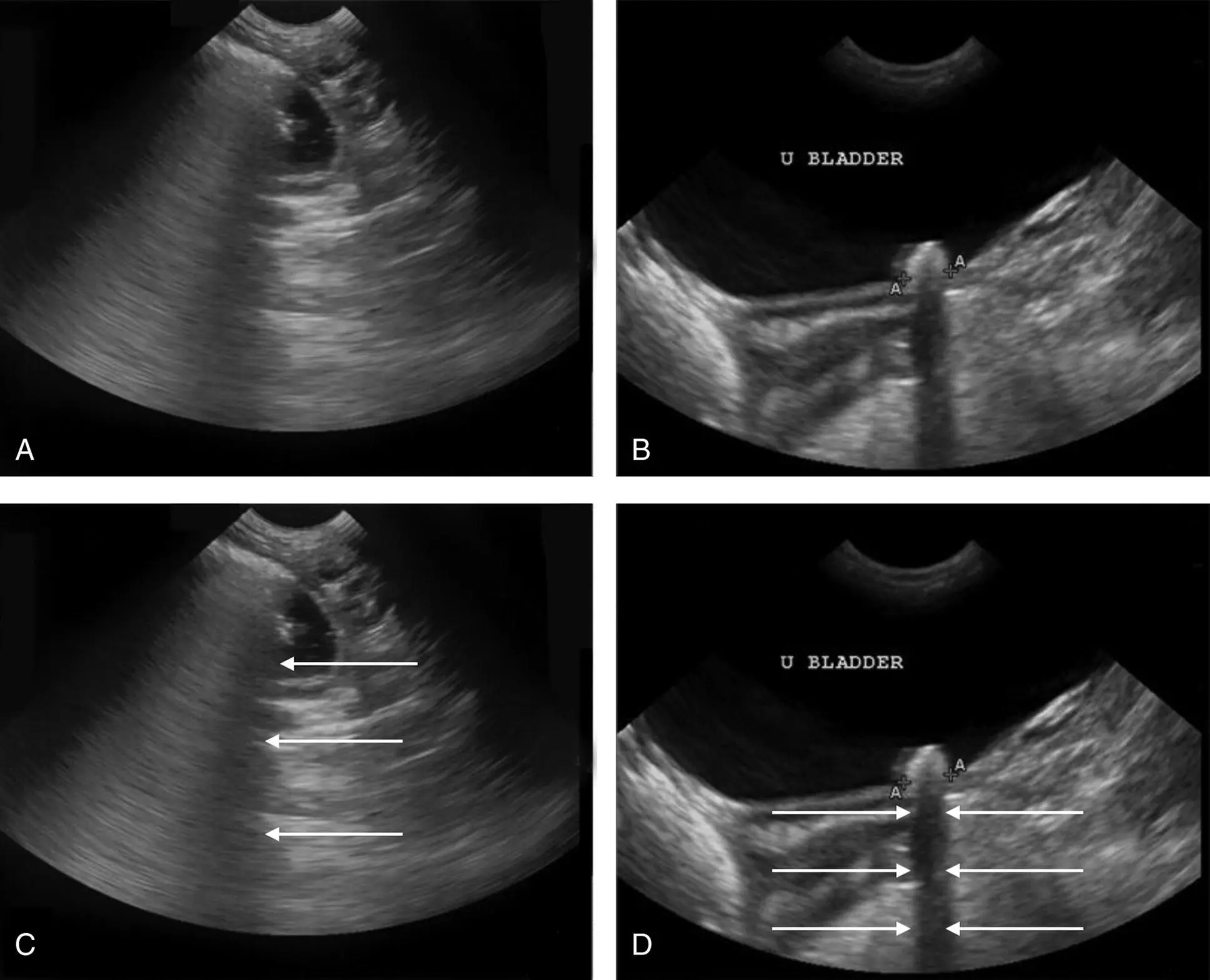

Figure 3.2. Edge shadowing artifact. (A) An edge shadowing artifact is seen arising from the curved edge on the left side of the stomach wall in this image, making its wall appear to extend distally as an anechoic (dark or black) line. A dirty gas shadow is also produced from gas within the stomach lumen that appears as "pseudo B‐lines." (B) An edge shadowing artifact at the apex of the urinary bladder makes it falsely appear to have a rent, which can fool the hasty sonographer into thinking the free fluid is from a ruptured bladder; however, note the smooth expected normal contour of the urinary bladder. In (C) the edge shadowing artifact is outlined with arrows (←). In (D) the edge shadowing creates a false rent in the wall of the urinary bladder ( circled ) and the superimposed curved line points out the edge shadowing from the curved surface of the urinary bladder wall extending through the far‐field.

Source: Courtesy of Dr Sarah Young, Echo Service for Pets, Ojai, California.

Acoustic Enhancement: Fluid‐Filled Structures

When the sound beam passes through a fluid‐filled structure, such as the gallbladder, urinary bladder, fluid‐filled stomach, eye, or a cyst, ultrasound waves do not become as attenuated as the neighboring waves passing through more solid tissues to either side of the structure. Therefore, the tissues on the far side of the fluid‐filled structure appear much brighter than the neighboring tissues at the same depth. Acoustic enhancement is obvious, looking past the fluid‐filled gallbladder and urinary bladder ( Figure 3.3). On the other hand, by realizing how the artifact is formed, the acoustic enhancement artifact can be useful to the savvy sonographer in determining if a structure of interest is fluid filled (brighter through the far‐field having acoustic enhancement) or soft tissue (lacking acoustic enhancement) (Penninck 2002) (see Figure 3.3).

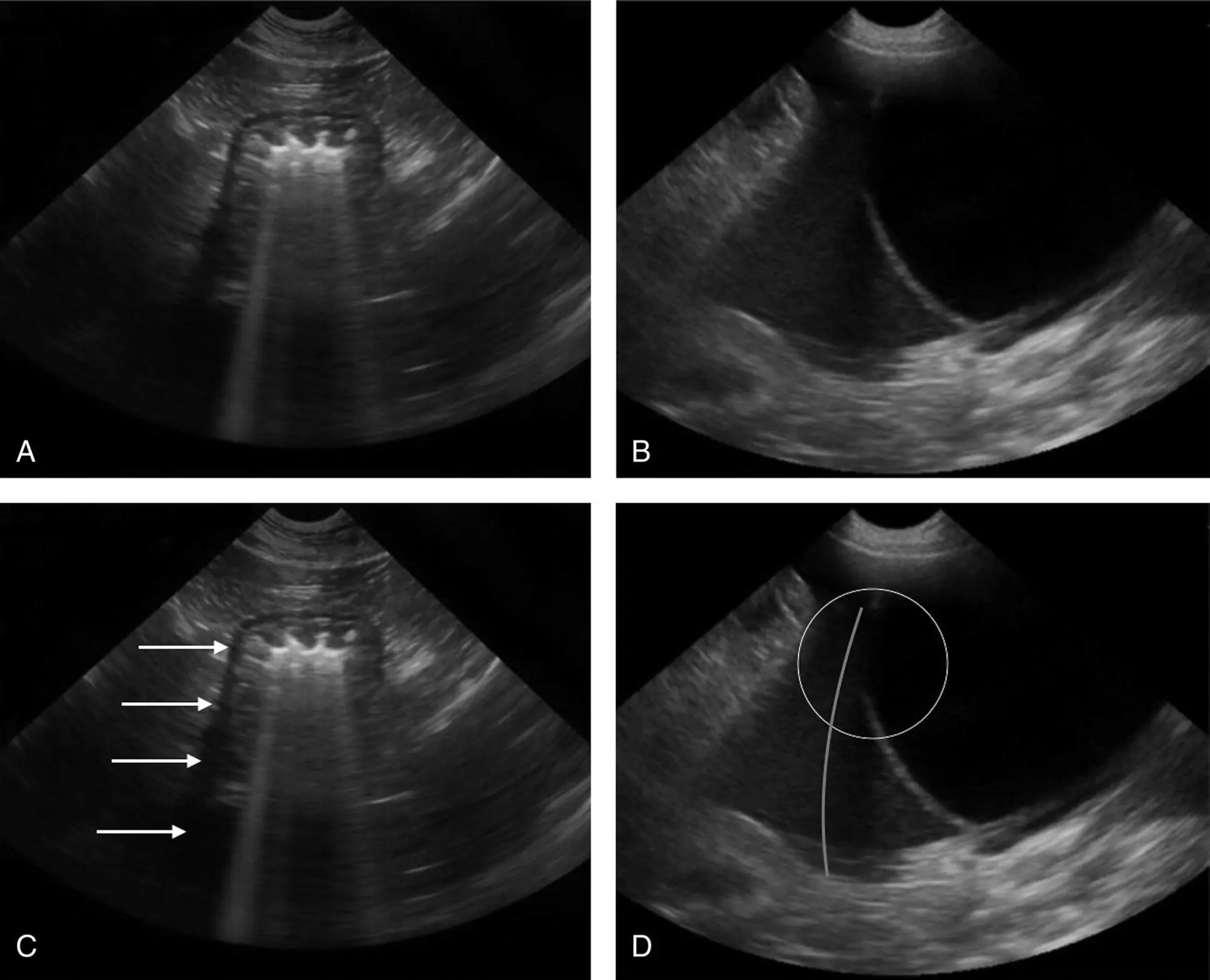

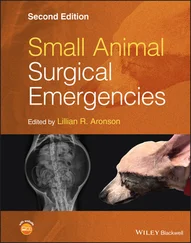

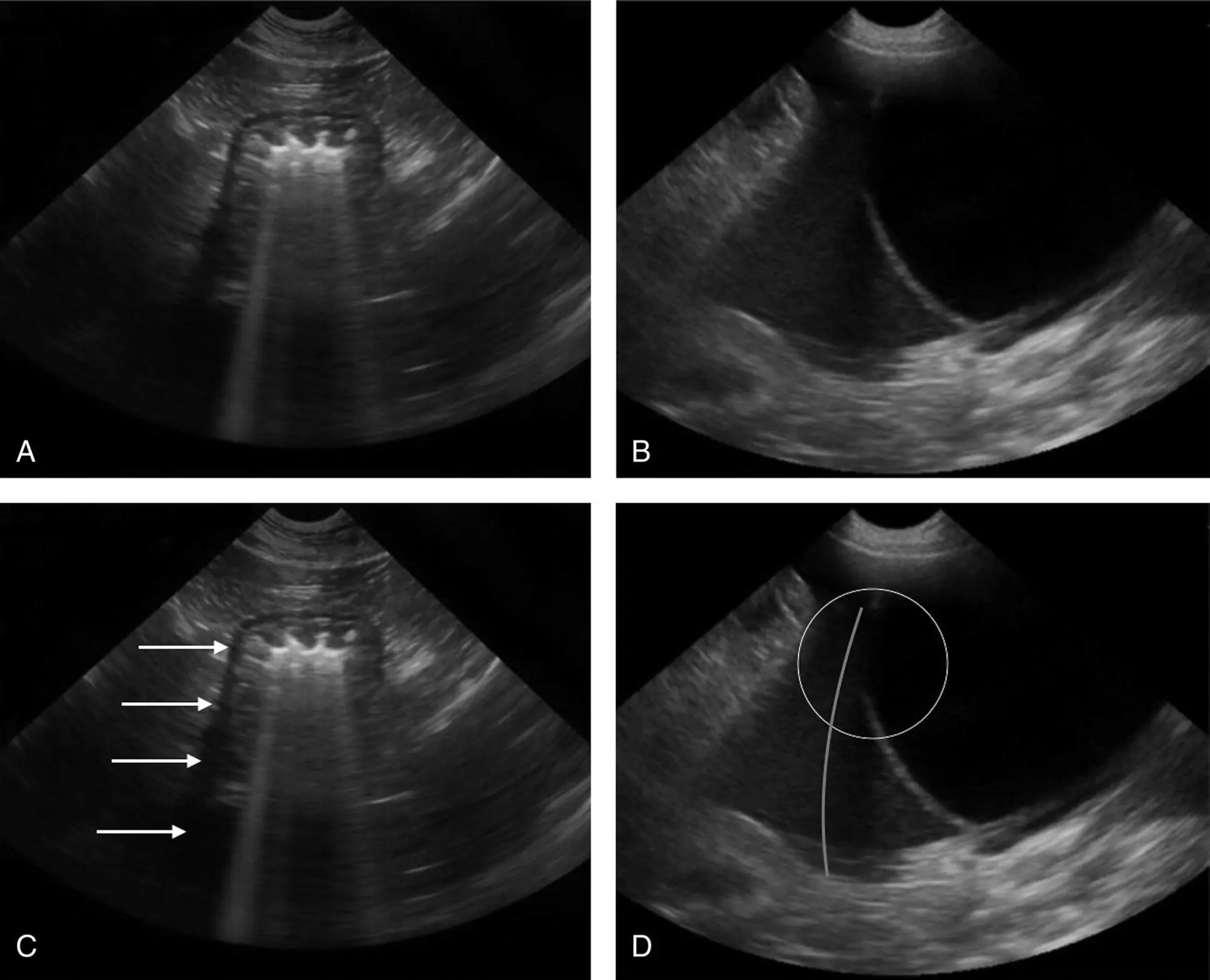

Figure 3.3. Acoustic enhancement artifact. Because there is less attenuation when sound moves through fluid, the area distal to a fluid‐filled structure will appear hyperechoic (brighter or whiter) to the surrounding tissue. Note the hyperechoic regions distal to the gallbladder (A) and distal to the urinary bladder (B) that are outlined with arrows (←) in (C) and by white bars in (D).

Artifacts of Velocity or Propagation

Mirror Artifacts: Strong Reflector (Air)

When we image a structure that is close to a curved, strong reflector such as the diaphragm (remember this is actually the lung–air interface following the curve of the diaphragm), a sound beam can reflect off the curved surface, strike adjacent tissues, reflect back to the curved surface, and then reflect back to the transducer. Because the processor only uses the time it takes for the beam to return home and cannot “see” the ongoing reflections, it will be fooled into placing (mirroring) the image on the far side of the curved surface. The classic place for a mirror artifact is at the diaphragm, and the classic mistake is interpreting the artifact as a diaphragmatic hernia (Penninck 2002) ( Figure 3.4).

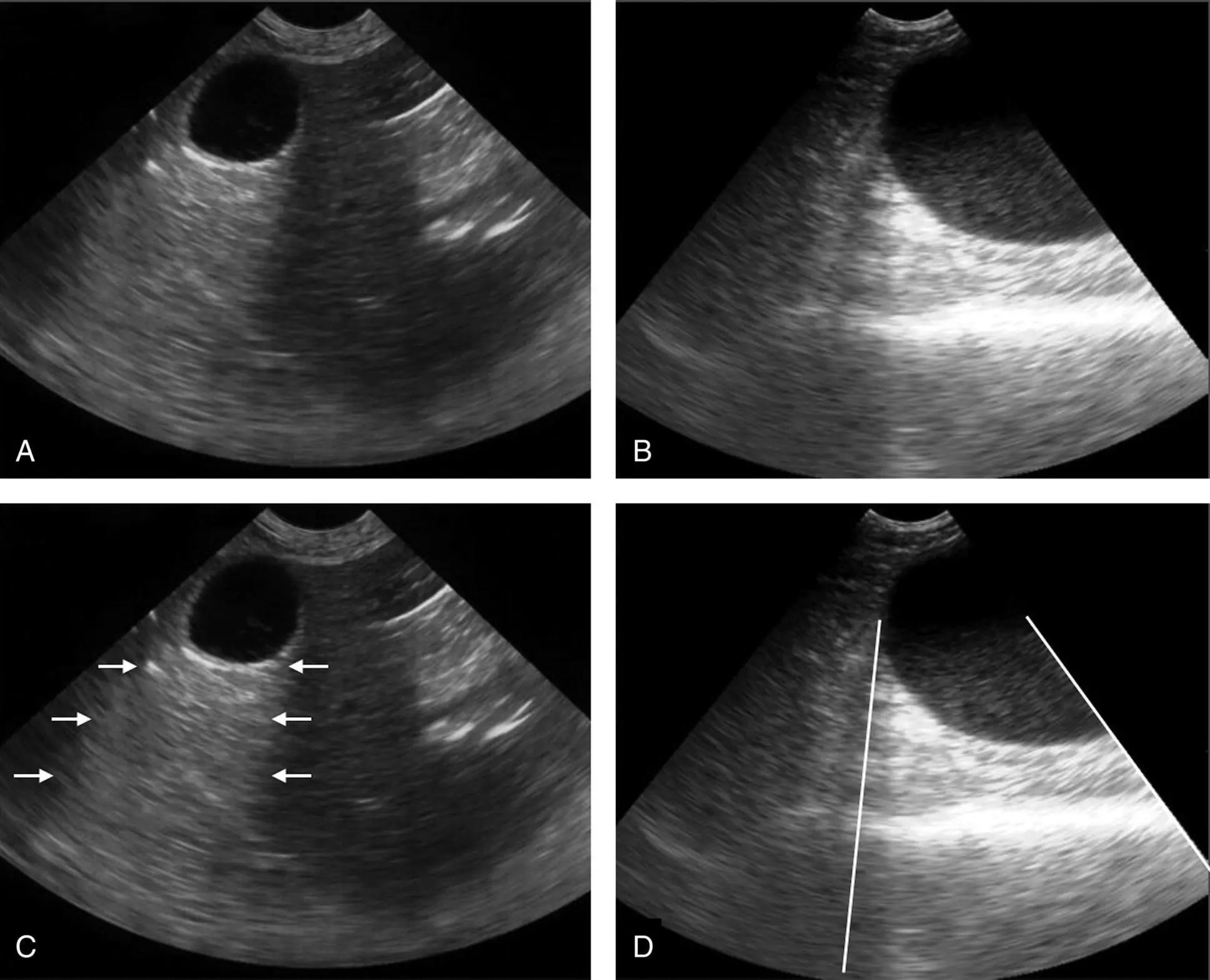

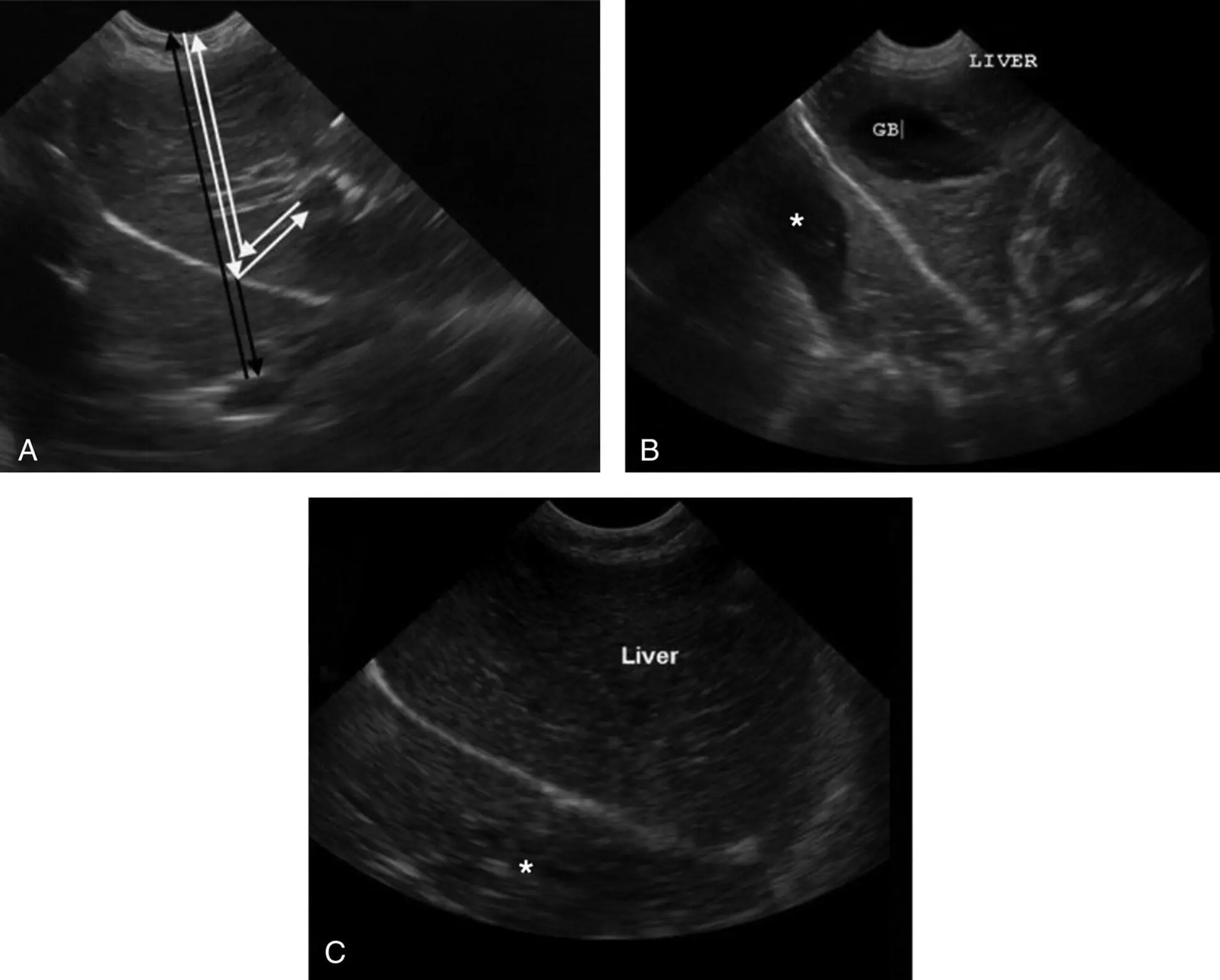

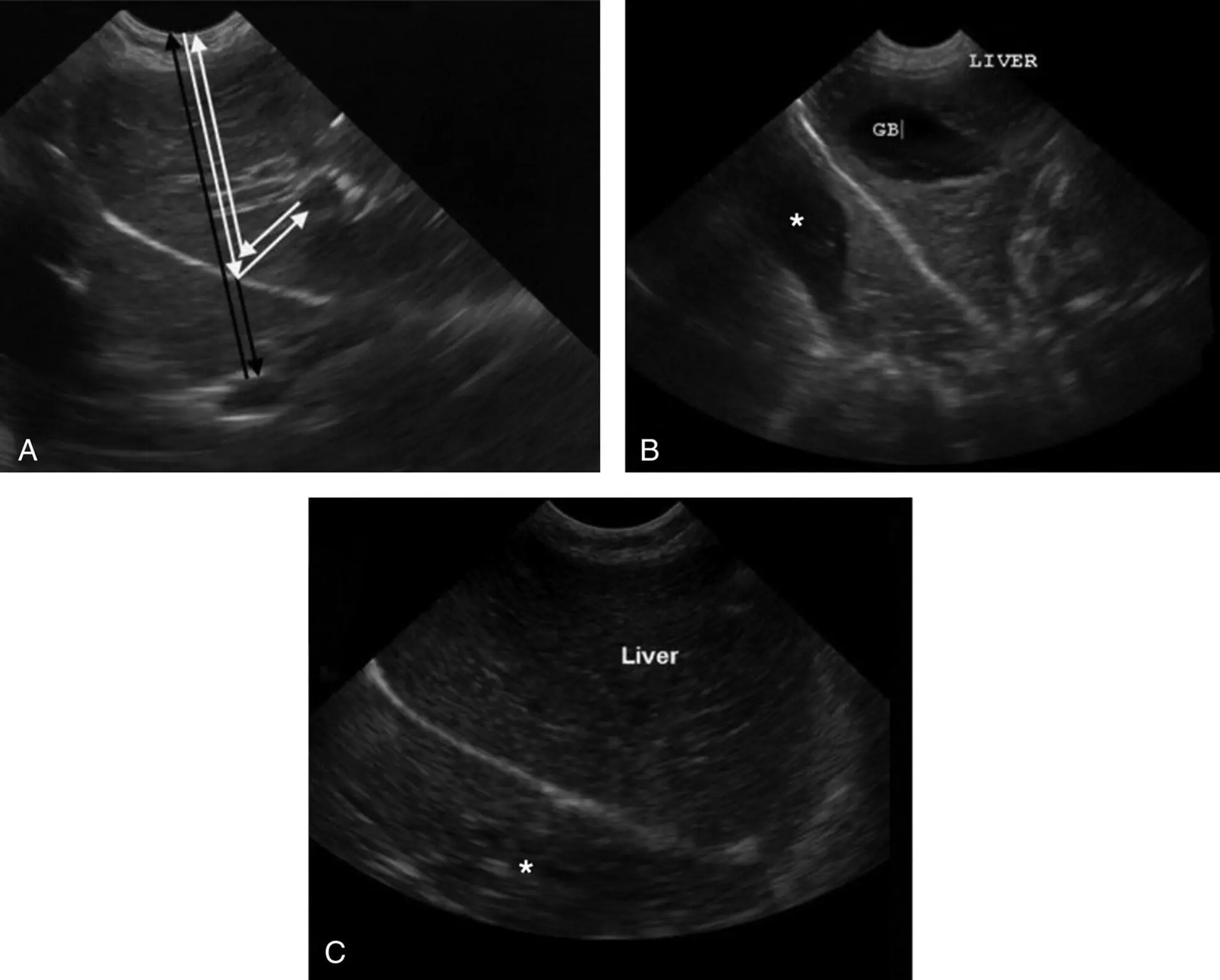

Figure 3.4.Mirror artifact. The gallbladder appearing to be on both sides of the diaphragm is the classic example of mirror artifact, created by a strong soft tissue–air interface. The mirror image artifact also may be generated under similar circumstances when the fluid‐filled urinary bladder lies against the air‐filled colon. (A) The white arrows illustrate the actual path of the sound beam reflecting off the curved lung–air interface against the diaphragm, while the black arrows illustrate the path perceived by the ultrasound processor. Note that the gallbladder falsely appears as if it is within the thorax, and should not be mistaken for a diaphragmatic hernia. (B) Mirror image artifact in which it appears that the liver and gallbladder are on both sides of the diaphragm (*). (C) Mirror image artifact in which it appears that liver (gallbladder not present in this view) is on both sides of the diaphragm (*).

Читать дальше