Recognizing the tablet PC

Recognizing the tablet PC

One summer day, in his 42nd year, Eugene noted how pleasant the weather was outside. He was inspired to attach wheels to the room-size, vacuum tube computer. Then he and the other three computer scientists, despite their utter lack of muscle tone, pushed the 17-ton beast out of the lab to work outside. It was this crazy notion that sparked the portable computer revolution.

Today the revolution continues. Computers are not only shrinking — they’re becoming more portable. Their names represent a pantheon of portable PC potential, including portables, laptops, notebooks, netbooks, convertibles, and tablets. Indeed, portable computing has a rich history, from the first dreams and desires to the multitudinous options now available.

The History of Portable Computing

You can’t make something portable by simply bolting a handle to it. Sure, it pleases the marketing folk, who are interested in things that sound good more than things that are practical. For example, you can put a handle on an anvil and call it portable, but that doesn’t make it so.

My point is that true portability implies that a gizmo has at least these three characteristics:

It’s lightweight.

It needs no power cord or other wires.

It’s practical.

In the history of portable computing, these three things didn’t happen all at once, and definitely not in that order.

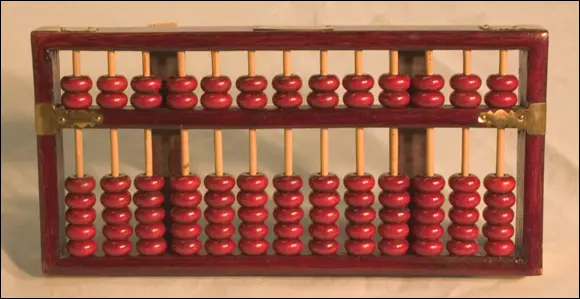

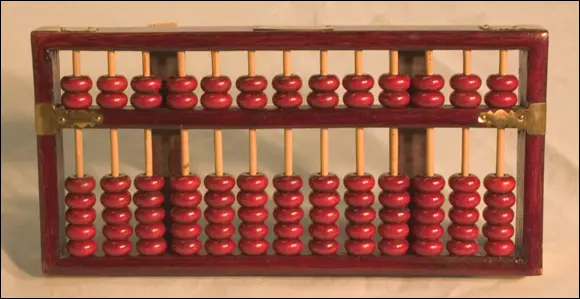

THE ANCIENT PORTABLE COMPUTER

Long before people marveled over credit-card-size calculators, merchants and goatherds used the world's first portable calculator. Presenting the abacus, the device used for centuries to rapidly perform calculations that would otherwise induce painful headaches.

Abacus comes from the Greek word meaning “to swindle you faster.” Seriously, the abacus, or counting board, is simple to master. Schoolkids today learn to use the abacus as a diversion from more important studies. In the deft hands of an expert, an abacus can perform all the same operations as a calculator — including square roots and cubic roots.

In his short story Into the Comet, science fiction author Arthur C. Clarke wrote of stranded astronauts using many abacuses to plot their voyage home when the spaceship's computer wouldn’t work because the Internet was down and their version of Windows couldn’t be validated.

The desire to take a computer on the road has been around a long, long time. Back around 1970, when Bill Gates was still in school and dreaming of becoming a chiropodist, Xerox PARC developed the Dynabook concept.

Today, you'd recognize the Dynabook as an eBook reader, similar to the Amazon Kindle: The Dynabook was proposed to be the size of a sheet of paper and only a half-inch thick. The top part was a screen; the bottom, a keyboard.

The Dynabook never left the lab, remaining only a dream. Yet the desire to take a computer on the road wouldn't go away. During the three decades after the Dynabook concept fizzled, many attempts were made to create truly portable computers.

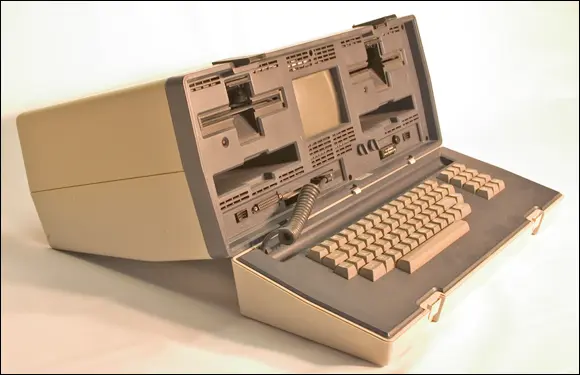

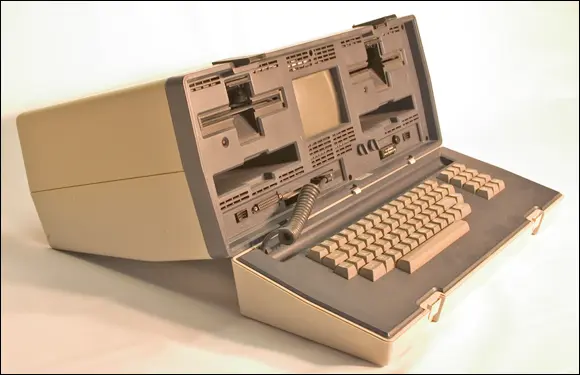

The first successful portable computer was the Osborne 1, created by computer book author and publisher Adam Osborne in 1981. Adam believed that in order for personal computers to be successful, they must be portable.

His design for the Osborne 1 portable computer was ambitious for the time: The thing needed to fit under an airline seat — and this was years before anyone would even dream of using a computer on an airplane.

The Osborne 1 portable computer, shown in Figure 1-1, was a whopping success. It featured a full-size keyboard and two 5¼-inch floppy drives but only a teensy, credit-card-size monitor. It wasn't battery powered, but it did have a handy carrying handle so that you could lug around the 24-pound beast like an overpacked suitcase. Despite its shortcomings, 10,000 units a month were sold; for $1,795, you got the computer plus free software.

The Osborne computer was barely portable. Face it: The thing was a suitcase! Imagine hauling the 24-pound Osborne across Chicago's O'Hare Airport. Worse: Imagine the joy expressed by your fellow seatmates as you try to wedge the thing beneath the seat in front of you.

Computer users yearned for portability. They wanted to believe the advertising images of carefree people toting the Osborne around — people with arms of equal length. But no hipster marketing term could mask the ungainly nature of the Osborne: Portable? Transportable? Wispy? Nope. Credit some wag in the computer press for dreaming up the term luggable to describe the new and popular category of portable computers ushered in by the Osborne.

FIGURE 1-1:A late-model Osborne.

Never mind its weight. Never mind that most luggable computers never ventured from the desktops they were first set up on — luggables were the best the computer industry could offer an audience wanting a portable computer.

In the end, the Osborne computer’s weight didn’t doom it. No, what killed the Osborne was that in the early 1980s the world wanted IBM PC compatibility. The Osborne lacked it. Instead, the upstart Texas company Compaq introduced luggability to the IBM world with the Compaq 1, shown in Figure 1-2.

The Compaq Portable (also called the Compaq 1), introduced in 1983 at $3,590, proved that you could have your IBM compatibility and haul it on the road with you — as long as a power socket was handy and you had good upper-body strength.

Yet the power cord can stretch only so far. It became painfully obvious that for a computer to be truly portable — as Adam Osborne intended — it would have to lose its power cord.

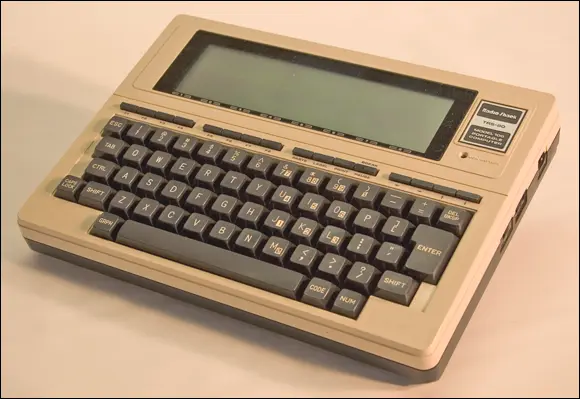

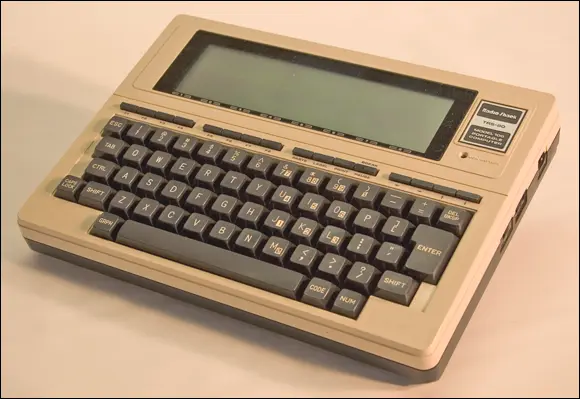

The first computer that looked even remotely like a modern laptop, and was fully battery powered, was the Radio Shack Model 100, shown in Figure 1-3. It was an overwhelming success.

FIGURE 1-2:The luggable Compaq Portable.

PC is an acronym for p olitically c orrect as well as for p ersonal c omputer. In this book’s context, the acronym PC stands for personal computer.

Originally, personal computers were known as microcomputers . This term comes from the microprocessor that powered the devices. It was also a derisive term, comparing the personal systems with the larger, more intimidating computers of the day.

When IBM entered the microcomputer market in 1982, it called its computer the IBM PC. Though it was a brand name, the term PC soon referred to any similar computer and eventually to any computer. A computer is basically a PC.

As far as this book is concerned, a PC is a personal computer that runs the Windows operating system. Laptop computers are also PCs, but the term PC more often implies a desktop model computer.

FIGURE 1-3:The Radio Shack Model 100.

Читать дальше

Recognizing the tablet PC

Recognizing the tablet PC