Sialadenosis, also known as sialosis, is a painless bilateral enlargement of the parotid glands and less commonly the submandibular and sublingual glands (see Chapter 6). It is typically bilateral and without inflammatory changes. No underlying mass is present. It has been associated with malnutrition, alcoholism, medications, and a variety of endocrine abnormalities, the most common of which is diabetes mellitus. In the early stages, there is gland enlargement but may progress to fatty replacement and reduction in size by late stages. By CT, there is slight increase in density of the entire gland in the early setting but the density decreases in the late stage when the gland is predominantly fatty. On T1 weighted MRI images in the early stage, the gland demonstrates a slight decrease in signal corresponding to the lower fat content and increased cellular component. T2 images show a slight increase in signal (Som and Curtin 1996; Bialek et al. 2006; Madani and Beale 2006a).

Approximately 80–90% of salivary calculi form in the submandibular gland due to the chemistry of the secretions as well as the orientation and size of the duct in the floor of mouth. Eighty percent of submandibular calculi are radio‐opaque while approximately 40% of parotid sialoliths are radio‐opaque (see Chapter 5). CT without contrast is the imaging modality of choice as it easily depicts the dense calculi ( Figures 2.56through 2.58). MRI is less sensitive and may miss calculi. Vascular flow voids can be false positives on MRI. MR sialography as previously discussed may become more important in the assessment of calculi not readily visible by CT or for evaluation of strictures and is more important as part of therapeutic maneuvers. US can demonstrate stones over two millimeters with distal shadowing (Shah 2002; Bialek et al. 2006; Madani and Beale 2006a).

This autoimmune disease affects the salivary glands and lacrimal glands and is designated primary Sjogren if no systemic connective tissue disease is present but designated secondary Sjogren if the salivary disease is associated with systemic connective tissue disease (Madani and Beale 2006a). The presentations vary radiographically according to stage. Typically, early in the disease the gland may appear normal on CT and MRI. Early during the disease, there may be premature fat deposition, which may be demonstrated radiographically and may be correlated with abnormal salivary flow (Izumi et al. 1997). Also, in the early course of disease, tiny cysts may form consistent with dilated acinar ducts and either enlarge or coalesce as the disease progresses. These can give a mixed density appearance of the gland with focal areas of increased and decreased density by CT and areas of increased and decreased signal on T1 and T2 MRI, giving a “salt and pepper” appearance (Takashima et al. 1991, 1992). There may be either diffuse glandular swelling from the inflammatory reaction or this may present as a focal area of swelling. The diffuse swelling may mimic viral or bacterial sialadenitis. The focal swelling may mimic a tumor, benign or malignant, including lymphoma. Pseudotumors may be cystic lesions from coalescence or formation of cysts or dilatation of ducts, or they may be solid from lymphocytic infiltrates (Takashima et al. 1991, 1992). As glandular enlargement and cellular infiltration replaces the fatty elements, the gland appears denser on CT and lower in signal on T1 and T2 MRI. But when chronic inflammatory changes have progressed, tiny or course calcifications may develop. The cysts are variable in size, and the larger cysts may represent confluent small cysts or abscesses. The CT and MRI appearance can be like that of lymphoepithelial lesions seen with HIV but does include calcifications. Typically, there is no diffuse cervical lymphadenopathy. The development of cervical adenopathy may indicate development of lymphoma (Takashima et al. 1992). Solid nodules or masses can also represent underlying lymphoma (non‐Hodgkin type) to which these patients are prone (Sugai 2002). The latter stages of the disease produce a smaller and more fibrotic gland (Shah 2002; Bialek et al. 2006; Madani and Beale 2006a).

Figure 2.56. Reformatted coronal contrast‐enhanced CT of the submandibular gland demonstrating a sialolith in the hilum of the right submandibular gland.

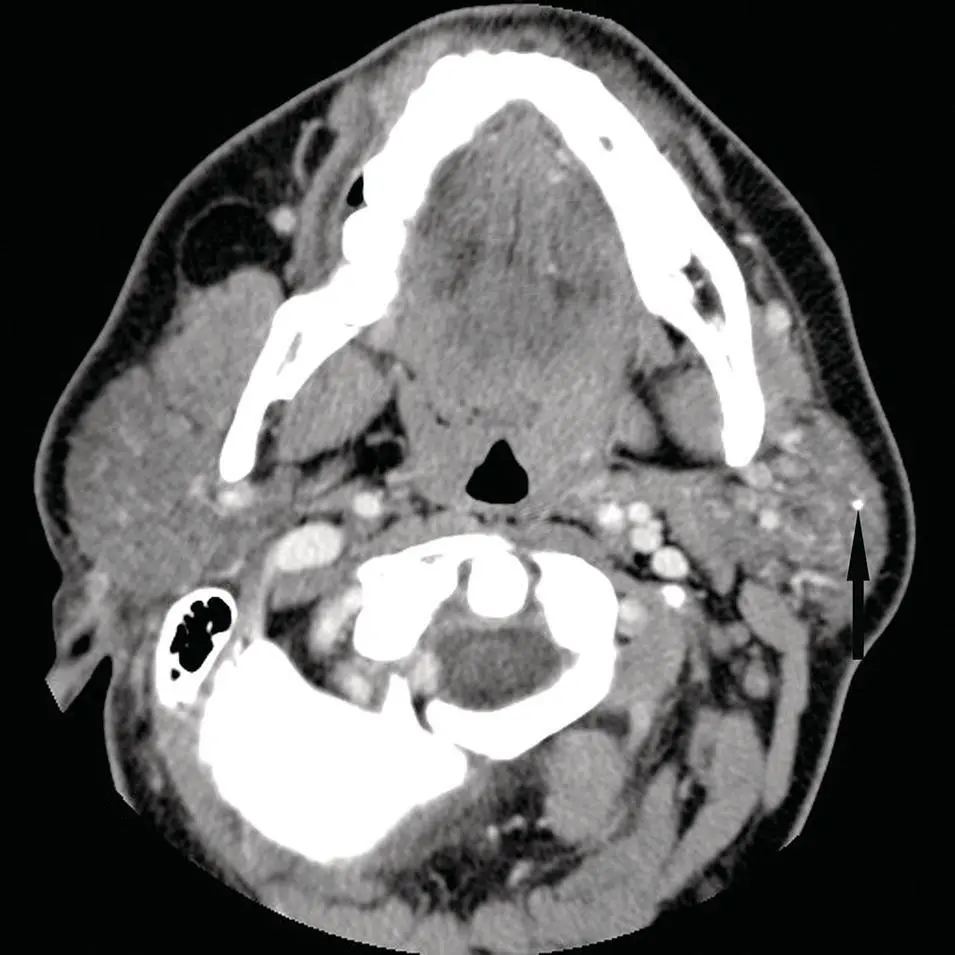

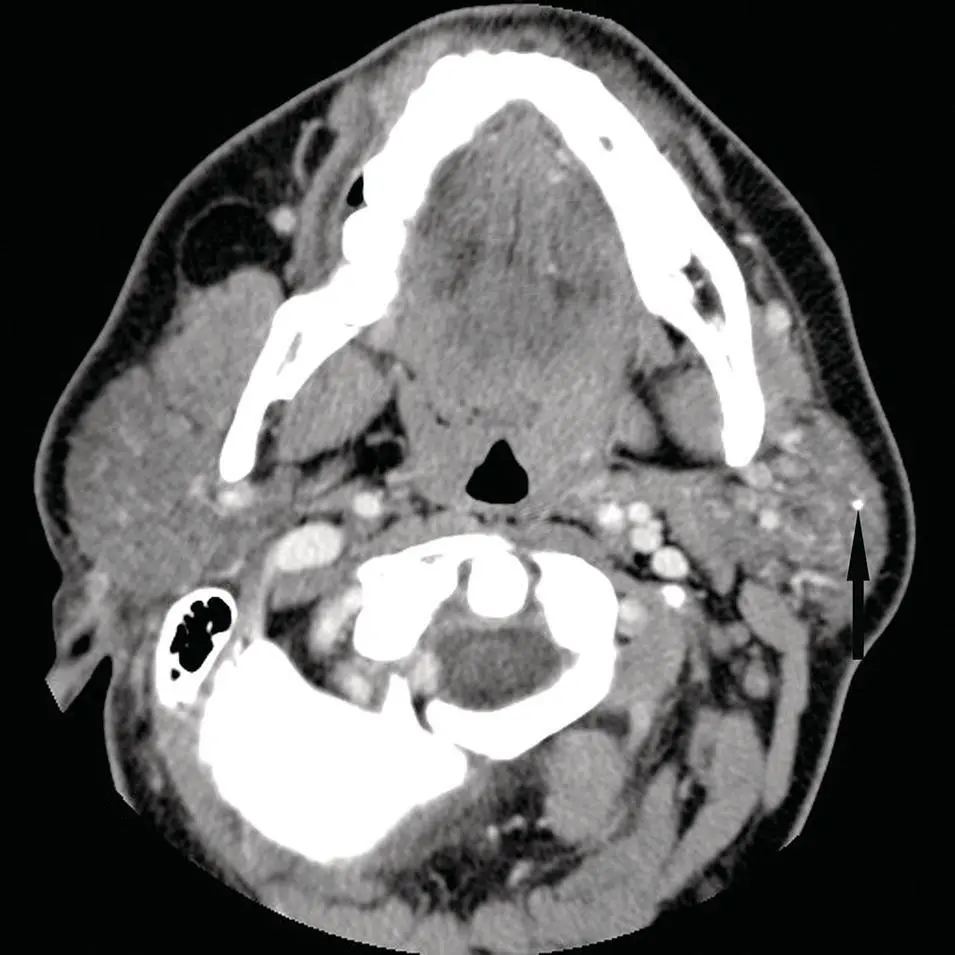

Figure 2.57.Axial contrast‐enhanced CT of the parotid gland demonstrating a small left parotid sialolith (arrow).

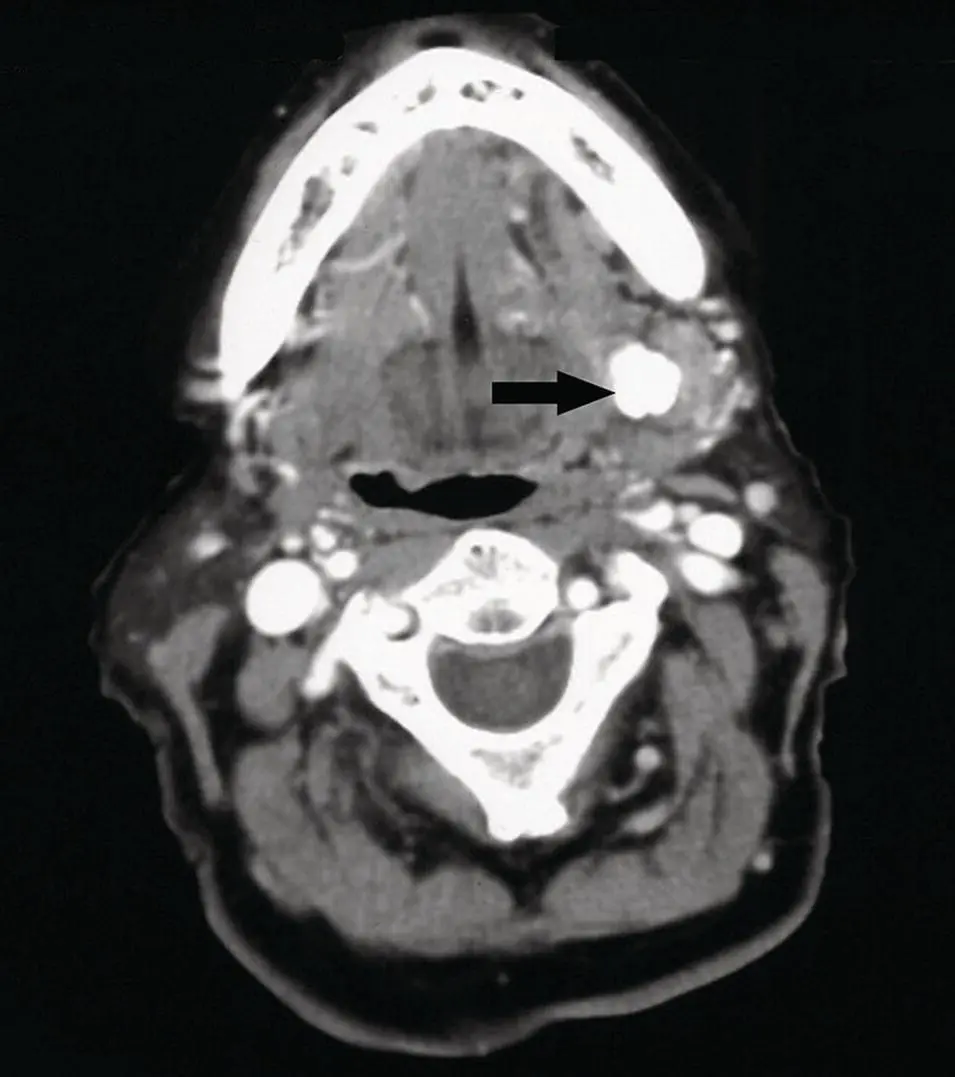

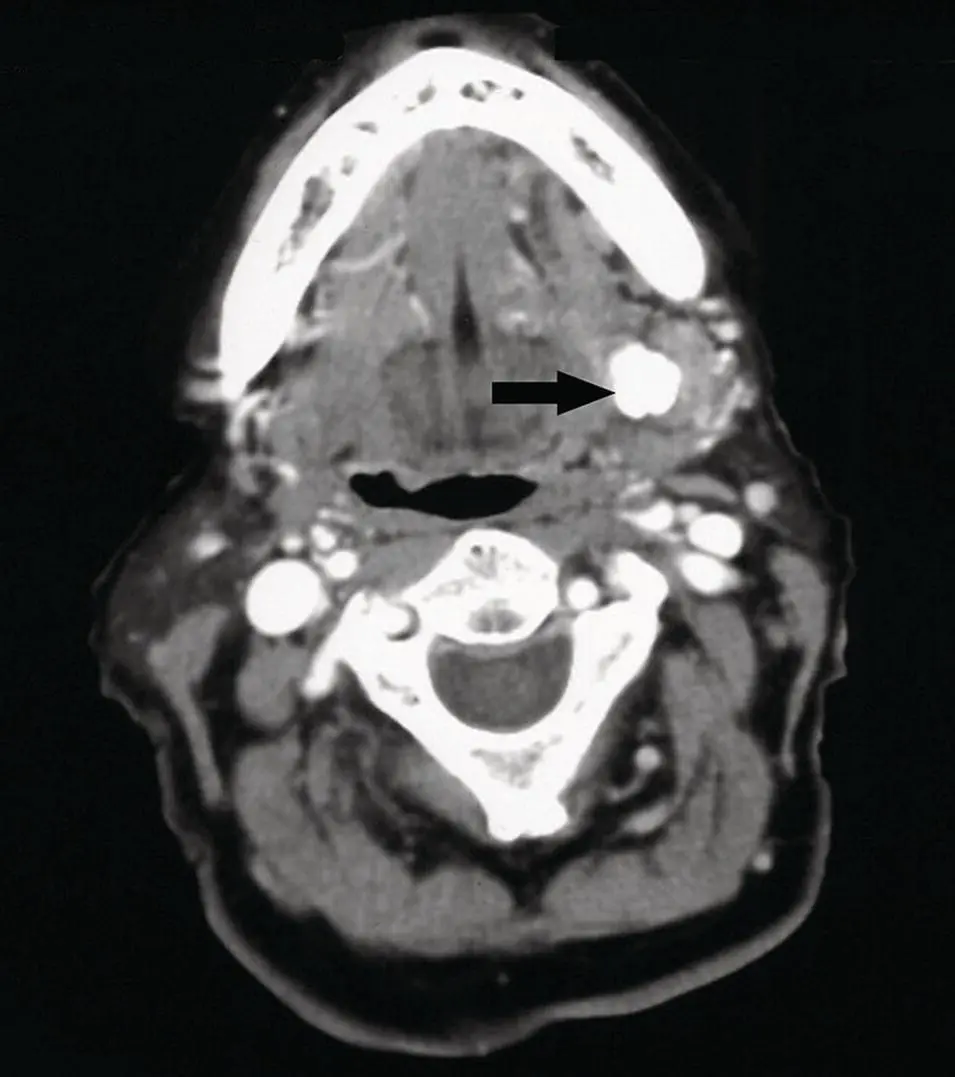

Figure 2.58. Axial contrast‐enhanced CT at the level of the submandibular glands with a very large left hilum sialolith (arrow).

Sarcoidosis is a granulomatous disease of unknown etiology (see Chapter 6). It typically presents with bilateral parotid enlargement. It may be an asymptomatic enlargement or may mimic a neoplasm with facial nerve palsy. The parotid gland usually demonstrates multiple masses bilaterally, which is a nonspecific finding and can also be seen with lymphoma, tuberculosis (TB) or other granulomatous infections, including cat‐scratch disease. There is usually associated cervical lymphadenopathy. The CT characteristics of the masses are slightly hypodense to muscle but hyperdense to the more fatty parotid gland. MRI also demonstrates nonspecific findings. Doppler US demonstrates hypervascularity, which may be seen with any inflammatory process. The classically described “panda sign” seen with uptake of 67Ga‐citrate in sarcoidosis is also not pathognomonic for this disease and may be seen with Sjögren syndrome, mycobacterial diseases, and lymphoma.

CONGENITAL ANOMALIES OF THE SALIVARY GLANDS

First Branchial Cleft Cyst

This congenital lesion is in the differential diagnosis of cystic masses in and around the parotid gland along with lymphoepithelial lesions, abscesses, infected or necrotic lymph nodes, cystic hygromas, and Sjögren syndrome. Pathologically, the first branchial cleft cyst is a remnant of the first branchial apparatus. Radiographically, it has typical characteristics of a benign cyst if uncomplicated by infection or hemorrhage, with water density by CT and signal intensity by MRI. It may demonstrate slightly increased signal on T1 and T2 images if the protein concentration is elevated and may be heterogenous if infected or hemorrhagic. Contrast enhancement by either modality is seen if infection is present. Ultrasound demonstrates hypoechoic or anechoic signal if uncomplicated and hyperechoic if infected or hemorrhagic. There is no increase in FDG uptake unless complicated. Anatomically, it may be intimately associated with the facial nerve or branches. They are classified as type I ( Figure 2.59) (less common of the two types) if found in the external auditory canal and type II if found in the parotid gland or adjacent to the angle of the mandible ( Figure 2.60) and may extend into the parapharyngeal space. It may have a fistulous connection to the external auditory canal or the skin surface. Infected or previously infected cysts may mimic a malignant tumor. Although not typically associated with either the parotid or submandibular glands, the second branchial cleft cyst, which is found associated with the sternocleidomastoid muscle and carotid sheath, may extend superiorly to the tail of the parotid or anteroinferiorly to the posterior border of the submandibular gland. It has imaging characteristics like the first branchial cleft cyst. Therefore, the second branchial cleft cyst must be differentiated from cervical chain lymphadenopathy or exophytic salivary masses. The third and fourth branchial cleft cysts are rare and are not associated with the salivary glands and are found in the posterior triangle and adjacent to the thyroid gland, respectively (Koeller et al. 1999).

Читать дальше