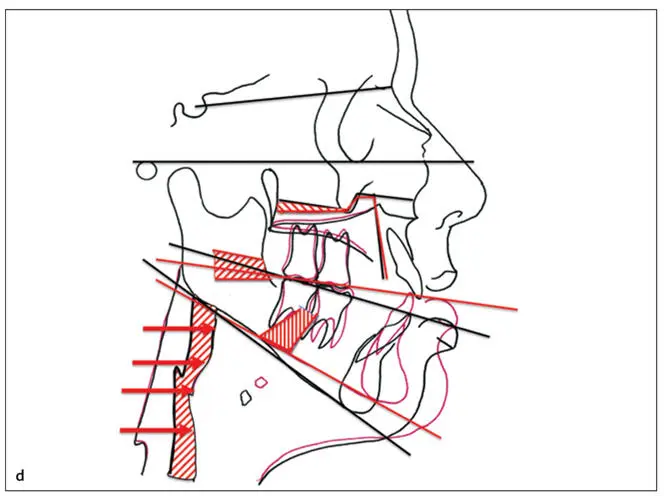

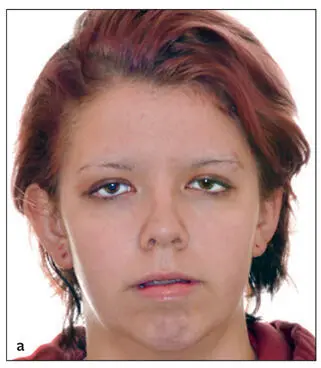

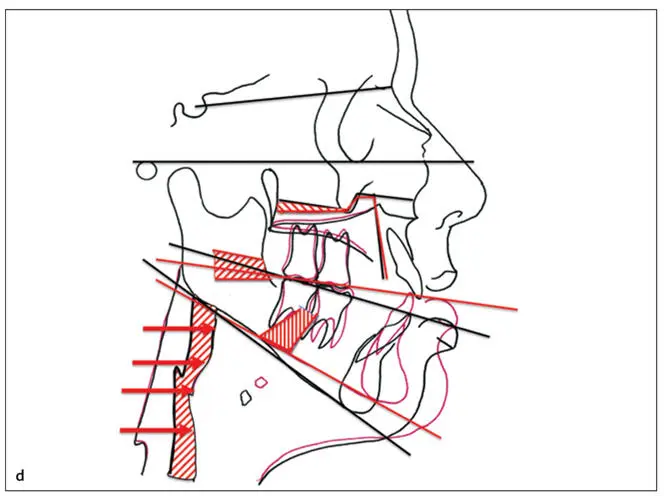

Vertical movements of the genial tubercles, or D-point, significantly affect the oropharyngeal airway in total airway volume, largely due to the positional changes of the suprahyoid musculature. It appears, however, that more sagittal movements of D-point have the greatest impact on Class II patients, and vertical movements have the greatest impact on Class III patients. With these changes in mind, it is important that the surgeon’s treatment plan take into consideration the skeletal geometry of their movements and how they will affect the airway. According to Steiner, a mandibular plane angle of 32 degrees (SN-mandibular plane; see Fig 2-51) is considered normal. As an example, a high angle (> 40 degrees) Class II malocclusion is best treated from an airway standpoint, with a counterclockwise rotation of the maxillomandibular complex, because this results in all of the favorable skeletal movements that have been shown to increase airway volume and minimal cross-sectional area, namely movement of PNS downward and D-point forward and upward (Fig 2-84).

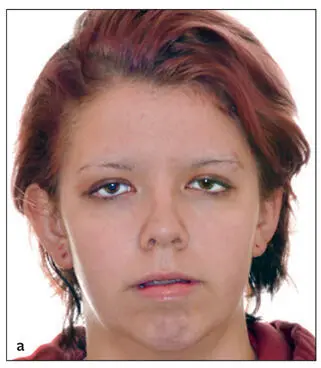

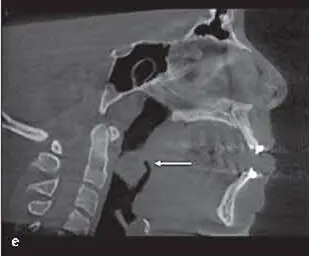

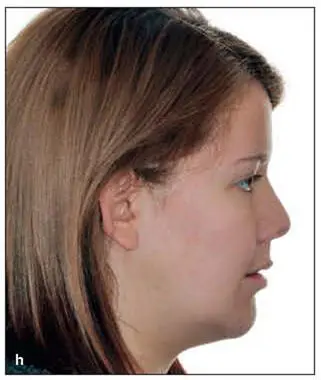

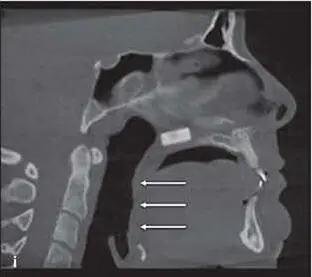

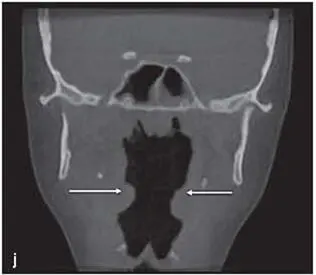

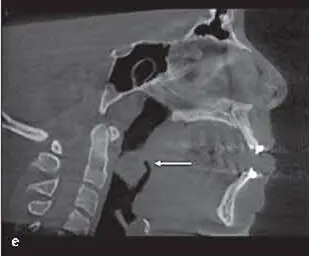

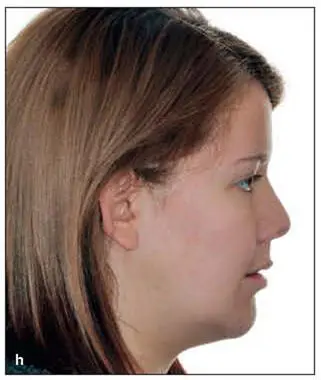

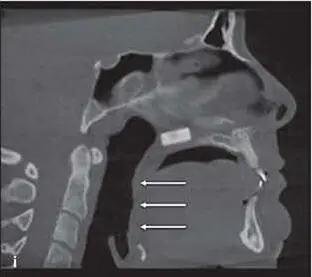

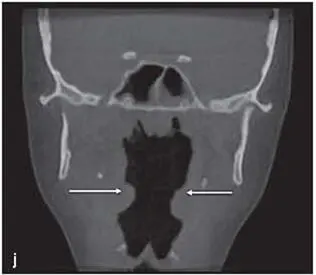

Fig 2-84This patient had severe OSA. (a) Presurgical frontal view. (b) Presurgical profile view. (c) Presurgical occlusion. (d) The surgical plan consists of a large counterclockwise rotational advancement, closing the open bite in the mandible. (e and f) CBCT images confirm marked airway compromise. (arrows) . (g and h) The upward and forward movement of the mandible restulted in significant postsurgical facial and skeletal changes. (i and j) The postoperative CBCT scans confirm a significant improvement in the airway anatomy (arrows) .

Class II patients

Some amount of maxillary advancement is often incorporated. Two-jaw surgery in Class II patients has a predictable improvement in the airway when the mandible is advanced. This improvement is even more pronounced when both jaws come forward or are rotated in a counterclockwise direction. ( Chapter 3discusses these treatment planning concepts in more detail.) In patients with Class II skeletal deformities, orthognathic surgery is used both to give the patient a better esthetic appearance and to alleviate airway concerns from a retrognathic mandible. Hernández-Alfaro et al (2011) performed a study on this topic. A retrospective evaluation of 30 patients who underwent maxillomandibular advancement, maxillary advancement, or mandibular advancement was performed. Three groups of 10 subjects each were established: group 1, bimaxillary surgery (Le Fort I maxillary osteotomy and mandibular bilateral sagittal split osteotomy with maxillomandibular advancement); group 2, maxillary advancement (Le Fort I maxillary osteotomy); and group 3, mandibular advancement (bilateral sagittal split osteotomy). Pre- and postoperative CBCT scans were taken in each case, and the changes in pharyngeal airway volume were compared.

A statistically significant increase in the pharyngeal airway volume occurred systematically. The average percentage of increase was 69.8% in group 1 and 78.3% in group 3. Group 2 exhibited a lower magnitude of increase (37.7%).

Class III patients

Class III patients are far more complicated because the skeletal deformity may have a mixed nature. In addition, the situation might include isolated maxillary hypoplasia, isolated mandibular hypoplasia, or a combination of maxillary hypoplasia and mandibular hyperplasia. The goal of a recent study by Rosário et al (2016) was to investigate whether advancement of the maxilla alone would affect the volume of the upper airway. CBCT scans were taken before and after surgery in 14 patients with a Class III skeletal deformity undergoing maxillary advancement exclusively. The effects of the procedure led to a mean increase in volume of 3.22 cm 3. Patient age and sex were not factors in the results.

As one might expect, mandibular setback surgery demonstrates a decrease in airway volume. In a study by Tselnik and Pogrel (2000), 14 patients had their pharyngeal airway space evaluated after mandibular setback surgery. Lateral cephalograms were obtained before surgery, immediately after surgery, and at long-term follow-up between 6 months and 2 years. The mean setback distance was 9.7 mm, which resulted in a long-term mean decrease in tongue base to posterior pharyngeal wall length of 4.77 mm. The area of the pharyngeal airway space decreased long-term an average of 1.52 cm 2. It was observed that outcome measurements increased at the immediate postoperative radiograph before decreasing at the long-term follow-up radiograph. This was thought to be from forward movement of the hyoid bone after surgery to preserve airway opening in the immediate postoperative period to prevent airway collapse. It is clear that individuals with short necks, obese individuals, or those with large tongues who have mandibular setbacks may be predisposed to the development of OSA, and patient selection should be carefully managed when planning isolated mandibular surgeries in those populations.

Given that there is improvement in the airway with isolated maxillary advancement and worsening of the airway dimensions with isolated mandibular setback, the better approach is strong consideration for two-jaw procedures. A small amount maxillary advancement can be effectively used to mitigate the negative impact of the mandibular setback. With that in mind, the authors rarely perform isolated mandibular procedures but instead opt for isolated maxillary advancement in those that can esthetically tolerate the surgical movement or a two-jaw procedure in those Class III patients who cannot.

Class III patients with normal mandibular plane angles can often be treated with linear movements. Class III patients with a high or low mandibular plane angle malocclusion can be more complicated and often require rotational movements. Low-angle (SN-mandibular plane < 22 degrees; see Fig 2-51) Class III patients often have overprojected chins due to vertical deficiency and/or overclosure. High-angle Class III patients, on the other hand, often have a short chin-throat dimension but a well-shaped chin. This scenario of course can lead to inadequate skeletal support for the airway. Low-angle Class III patients esthetically benefit from clockwise movements to deemphasize the chin and magnify the movement of the midface, but high-angle Class III patients often benefit esthetically from counterclockwise movements. Though this sounds counterintuitive, a counterclockwise rotation point around the incisors or B-point results in minimal chin movement and proportionately more posterior incisor movement. The D-point is often superior movement, which has a very positive effect on airway dimensions (Fig 2-85).

Читать дальше