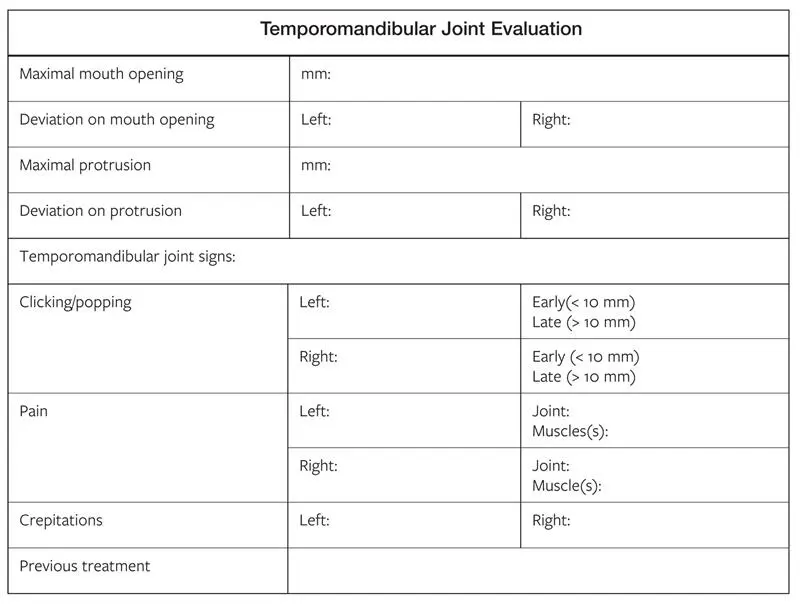

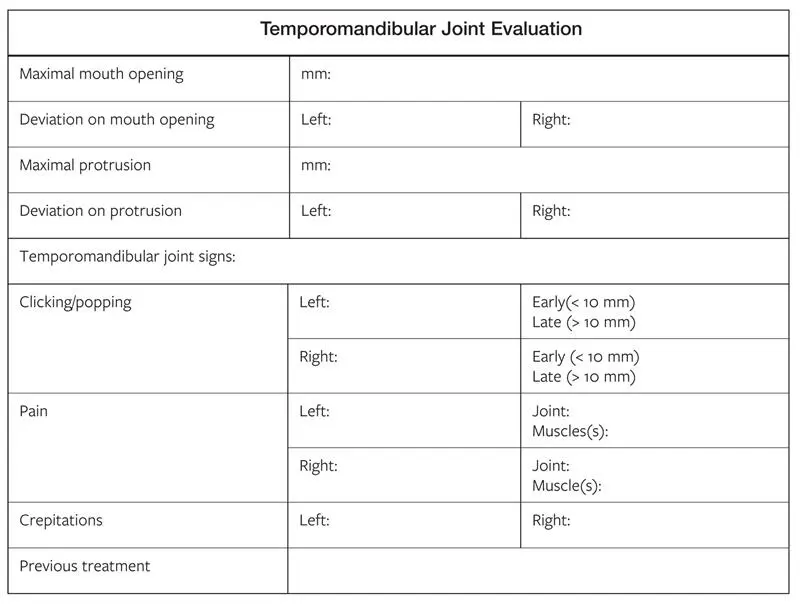

Careful documentation of TMJ pretreatment status is very important (Fig 2-80). The correct positioning of the condyle in the fossa is a critical aspect of the orthognathic surgical procedure, and information gathered at the pretreatment evaluation may be useful during surgery. The patient should also understand that correction of the dentofacial deformity and malocclusion will not necessarily correct a TMJ problem. Some clinicians believe it to be advantageous to perform TMJ surgery and orthognathic surgery simultaneously.

Fig 2-80TMJ evaluation form.

According to an evidence-based systematic review of temporomandibular dysfunction, Rinchuse and McMinn came to the following conclusions:

There is evidence-based support for the use of occlusal splints and biofeedback to treat temporomandibular joint disorders (TMDs).

There is no evidence supporting the treatment of TMDs by occlusal adjustments in orthodontic patients.

Occlusion, which was once considered to be the primary and sole cause of TMDs, now is only recognized as having a secondary role in causing it (if any role at all).

Orthodontic treatment to improve the occlusion does not cause TMDs.

Several clinicians studied the effect of orthognathic surgery on patients with signs and symptoms of TMDs. When comparing and contrasting their findings, some observations can be made (Onizawa et al 1995, Panula et al 2000, Dervis et al):

Patients scheduled for orthognathic surgery did not have significantly different TMD signs and symptoms than patients in the control group.

TMD signs and symptoms frequently improved in patients following orthognathic surgery.

Not all TMD patients improved following orthognathic surgery. For some patients, the signs and symptoms got worse.

Masticatory muscle and joint tenderness frequently improved following orthognathic surgery.

In most patients, the maximum mouth opening decreased following orthognathic surgery; however, this was clinically insignificant.

Airway Considerations in Orthognathic Surgery

It has been estimated that anywhere between 9% to 24% of men and 4% to 9% of women between the ages of 30 to 60 years are affected by obstructive sleep apnea (OSA). It is further estimated that 80% to 90% of those affected remain undiagnosed. Though, historically, cephalometric evaluations and clinical evaluations have been relied on in treatment planning for corrective jaw surgery with an end result of dental stability, skeletal stability, and a pleasing esthetic outcome, the impact on the airway must now be factored in for all treatment plans. Orthognathic surgery can either dramatically improve the airway or potentially compromise it.

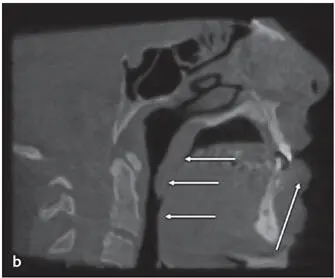

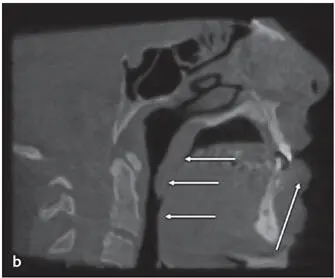

Features of patients with compromised airways include those with maxillary and/or bimaxillary retrusion, lower facial height, large tongue, elongated soft palate, inferior hyoid position, and those who tend to have a head-up posture in an effort to dilate the airway in addition to one of these other symptoms (Fig 2-81).

Fig 2-81 (a) Note short chin-throat length (1), narrow oropharyngeal airway (2), and mandibular retrusion (3) and large distance from hyoid cartilage to mandible (4) in a patient with an obstructed airway. (b) CBCT scan shows significant narrowing at the base of the tongue in the naso and oropharynx region (arrows) . The patient’s head is up here, but a head-down position results in near complete obstruction.

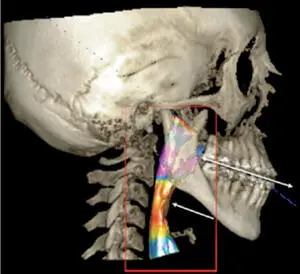

Individuals with high mandibular plane angles in addition to steep occlusal planes are often accompanied by a skeletal Class II pattern. However, it is possible to have a skeletal Class III high-angle skeletal structure with a short chin-throat dimension that may also present with a narrow oropharyngeal airway dimension (Fig 2-82). Lateral cephalometric analysis has been the most widely reported in the literature for evaluating the posterior airway space (PAS); however, an intraoperative fiber-optic pharyngoscopy can be used as well. With the prevalence of CBCT scanning, volumetric area measurements are possible, and these can also be correlated with compromised airways.

Fig 2-82Patients with a high mandibular plane and Class III malocclusion often have good chin projection but narrowed airways (arrow) . Linear movements can exacerbate airway problems, especially with the mandible moving backward along a steep occlusal plane.

Landmarks and measurements

Cephalometric airway analysis reveals that the soft palate anteroposterior (AP) dimension in a normal individual is approximately 10.0 mm. A retrognathic patient will have 7.4 mm of PAS, and a prognathic patient will typically have 12.5 mm or more. The dimensions of the tongue base are 11.0 mm, 8.3 mm, and 12.8 mm, respectively, for normal, retrognathic, and prognathic patients. Early studies indicate that a PAS less than 11.0 mm and a mandibular plane to hyoid distance of greater than 15.4 mm was associated with OSA. Those with a posterior airway space of less than 5.0 mm and a hyoid distance of greater than 24.0 mm tended to demonstrate the worst respiratory deficiencies. Recent studies disputed this and indicated that no one skeletal or soft tissue parameter can be directly linked to OSA; however, it is important that one pay close attention to airway dimensions so that treatment planning can be used to achieve positive effects on the airway, if warranted, or to at least minimize the effects of surgical movements.

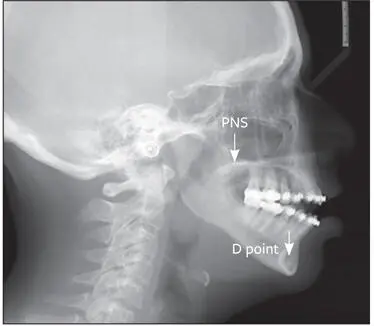

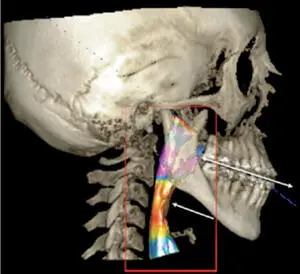

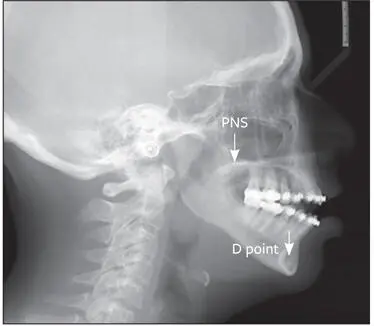

Important cephalometric landmarks to be mindful of are the potential changes in the vertical and AP positions of the PNS and D-point (Fig 2-83). Recent studies have demonstrated that significant airway volume changes occurred when PNS moved vertically and D-point (which essentially corresponds to the genial tubercles) moved in a horizontal or an upward vertical direction. The data further indicated that there was an increase or decrease of 2% of the total airway volume for every millimeter of directional change in these points. Furthermore, certain vertical and horizontal movements tend to impact various areas of the airway differently. When PNS was moved inferiorly, the oropharynx tended to have a smaller total volume; however, the nasopharynx enlarged. If PNS moved superiorly, then airway volume increased, but it was at the expense of the nasopharyngeal airway; when the airway lengthened, the nasopharyngeal airway narrowed as a result. With this in mind, one needs to be cautious with maxillary movements that result in the PNS moving upward. These should be offset with advancement of both jaws to promote airway increases as well as increases in the minimal cross-sectional area. Simple autorotation of the mandible after a posterior impaction of the maxilla is not nearly as predictable relative to its impact on improving the airway as is a mandibular advancement in the correction of the skeletal Class II malocclusion. Therefore, it may be strongly considered that both jaws be surgically corrected in patients with airway issues.

Fig 2-83Important anatomical landmarks when treatment planning include the PNS and D-point, which corresponds to the approximate position the genioglossal tubercles though centered in the symphysis (arrows) . Movement of PNS downward and D-point upward and forward have positive effects on airway volume.

Читать дальше