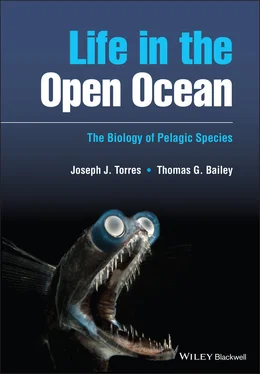

Joseph J. Torres - Life in the Open Ocean

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Joseph J. Torres - Life in the Open Ocean» — ознакомительный отрывок электронной книги совершенно бесплатно, а после прочтения отрывка купить полную версию. В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: unrecognised, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Life in the Open Ocean

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Life in the Open Ocean: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Life in the Open Ocean»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Life in the Open Ocean: The Biology of Pelagic Species

Life in the Open Ocean: The Biology of Pelagic Species

Life in the Open Ocean — читать онлайн ознакомительный отрывок

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Life in the Open Ocean», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

Source: NASA.

Ocean Circulation

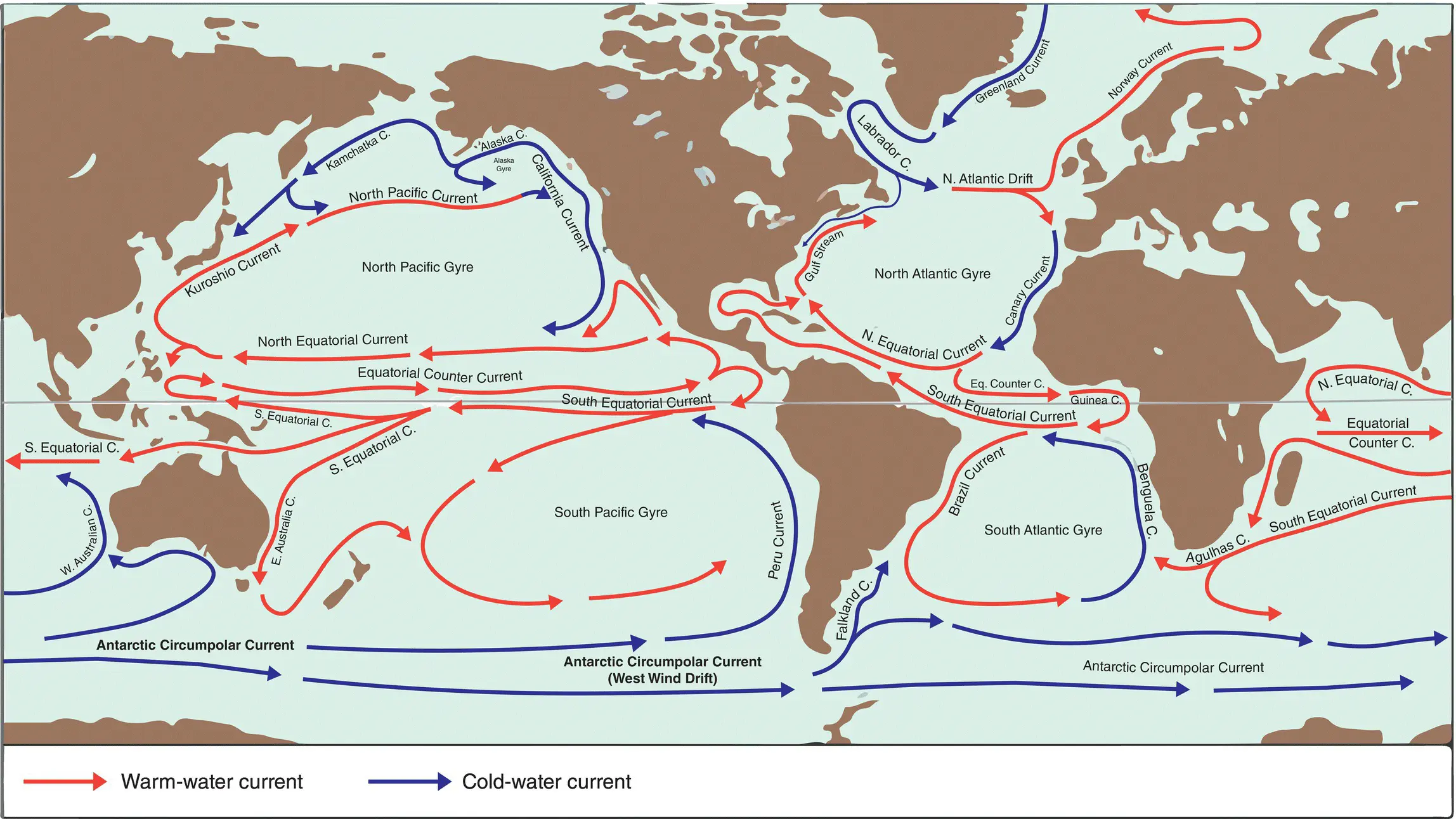

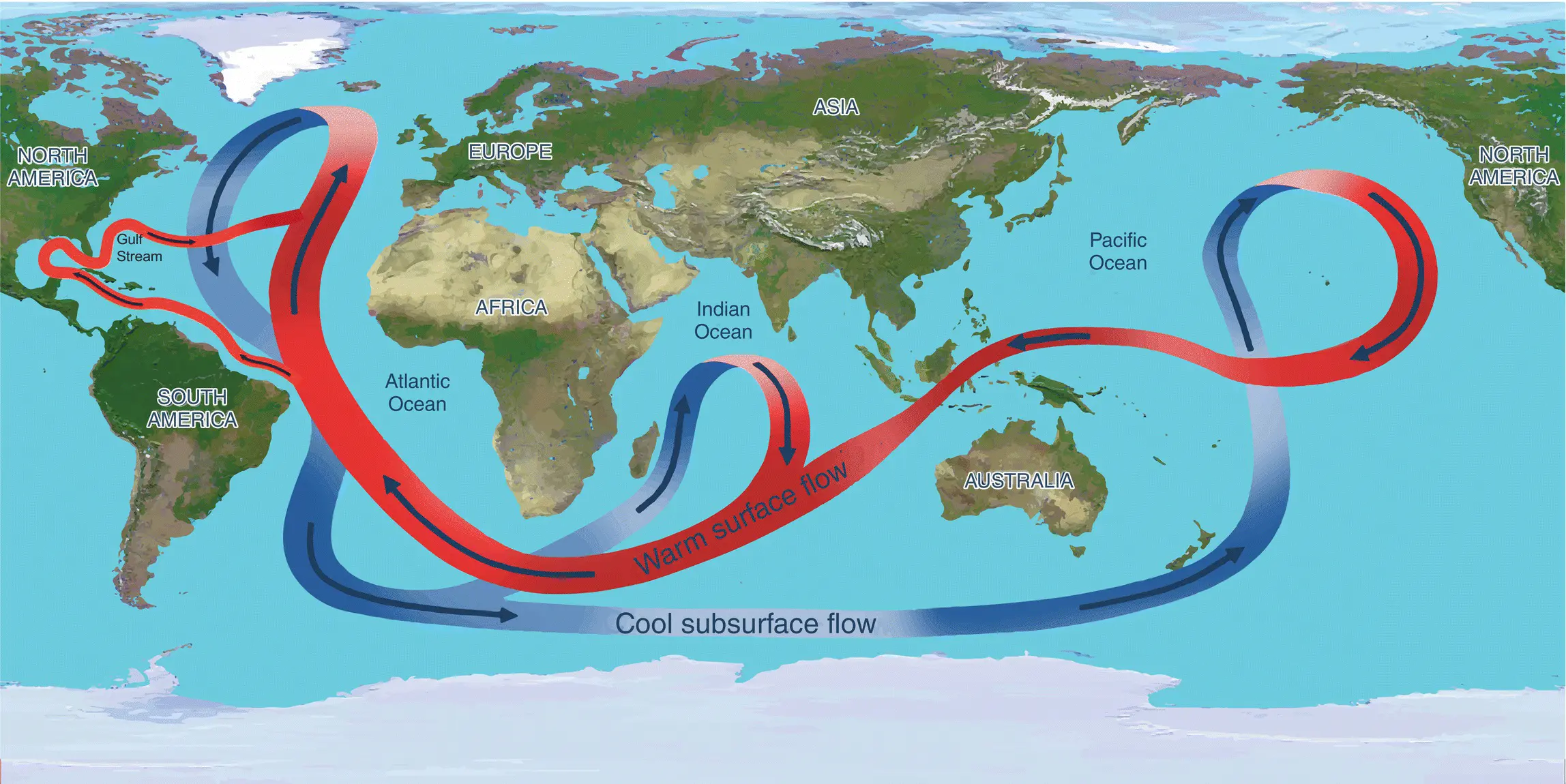

For our purposes, ocean currents are of two basic types: surface and deep. Surface currents ( Figure 1.5) are responsible for transport of about 10% of the oceanic volume and extend to about 400 m. The Earth’s prevailing winds interact with surface waters through friction, literally driving the water before them and forming large current systems, or gyres, in each of the ocean basins. The gyres circulate clockwise in the northern hemisphere and counterclockwise in the southern. The trade winds, persistent surface easterlies between the equator and about 30° latitude, are a major driving force for the central ocean gyres and were critical to past exploration and commerce. Deep‐ocean currents ( Figure 1.6) transport the remaining 90% of the oceanic volume and are the result of the Earth’s thermohaline circulation or the “Great Ocean Conveyor” (Broecker 1992).

Surface Currents: Ocean Gyres and Geostrophic Flow

Four forces combine to produce the surface currents in the global ocean: surface winds, the Sun’s radiation, gravity, and the Coriolis force. Let us begin with the most complicated: the Coriolis force, sometimes known as the Coriolis effect.

Figure 1.5 Geostrophic (surface) currents.

Source: NASA.

Figure 1.6 Thermohaline (deep) currents.

Source: NOAA.

Coriolis Force

The Coriolis force, as it applies to water movement in the oceans, is a result of the fact that the vast majority of the ocean’s volume is only loosely coupled to the surface of the Earth. The “no slip” condition, discussed in the section on viscosity, applies only to the boundary formed by the ocean bottom. The remaining volume of the ocean moves with the Earth as it rotates, but there is slippage due to the near absence of frictional coupling.

Consider the fact that the Earth is a sphere rotating from west to east. Now imagine that the Earth is sliced in half at the equator and we are looking down at it. It would appear as a disk that rotates through 360° in a 24‐hour period. Now imagine taking another slice of the Earth about halfway between the equator and the North pole. This second slice will also appear as a disk but a smaller one than the disk described by the equator ( Figure 1.7a). It will also rotate through 360° in a 24‐hour period but, because the circumference of this smaller disk is less than the equator’s disk, its velocity of rotation is also less. A city on the equator – Bogotá, Colombia, for example – is moving at a velocity of 1668 km h −1as the Earth rotates. Meanwhile Ottawa, Canada, at about 45 °N, is moving at 1180 km h −1( Figure 1.7b). The difference in relative velocities with latitude accounts for a difference of nearly 500 km traveled per hour and is at the heart of the Coriolis effect.

A classic example of the effect of the Coriolis force is to envision a missile or cannonball being fired northward from Bogotá at the equator. Let us stick with the missile. Because it was fired from the equator, the missile has an eastward velocity of 1668 km h −1when it leaves the ground, along with its northward velocity. As it speeds north the Earth is rotating beneath it, so the velocity at the Earth’s surface is declining with increasing distance from the equator. The result is that the missile, when viewed from the perspective of missile control at the equator, has veered to the right or clockwise ( Figure 1.8). Imagine now a similar experiment with the missile being fired from latitude 45 °N toward the equator. The missile has an eastward velocity of 1180 km h −1when it leaves the launch pad and is heading south toward the equator, which is moving east at 1668 km h −1. In this case, the Earth is literally moving east more quickly than the missile is moving as it heads south and, once again, the missile appears to veer to the right or clockwise.

This brings us to three general rules about Coriolis force. In the northern hemisphere, the Coriolis force deflects moving bodies, including fluids, in a clockwise direction: to the right. In the southern hemisphere, deflection is counterclockwise, to the left. Third, Coriolis force is nonexistent at the equator and strongest at the poles. Consider also that the influence of the Coriolis force will be very much greater on slow‐moving bodies such as parcels of water than on a quickly moving object such as our imaginary missile, which spends only minutes in the air.

The effect of the Coriolis force on ocean circulation is evident in Figure 1.5. In the North Atlantic gyre, the westerlies initially drive the water to the northeast, but the Coriolis force deflects the currents to the right, producing an easterly flowing current that is eventually deflected southward by the continental margins of Europe and Africa. The flow of the current is approximately 45° to the right of the wind direction. Its analogue in the South Atlantic, driven westward by the trade winds, is the North Equatorial Current. The circuit is completed by the powerful Gulf Stream on the western limb and the Canary Current on the eastern one.

Figure 1.7 Coriolis effect. Differences in velocity of Earth's surface as a function of latitude. (a) Equatorial view. (b) Polar view.

Ekman Transport

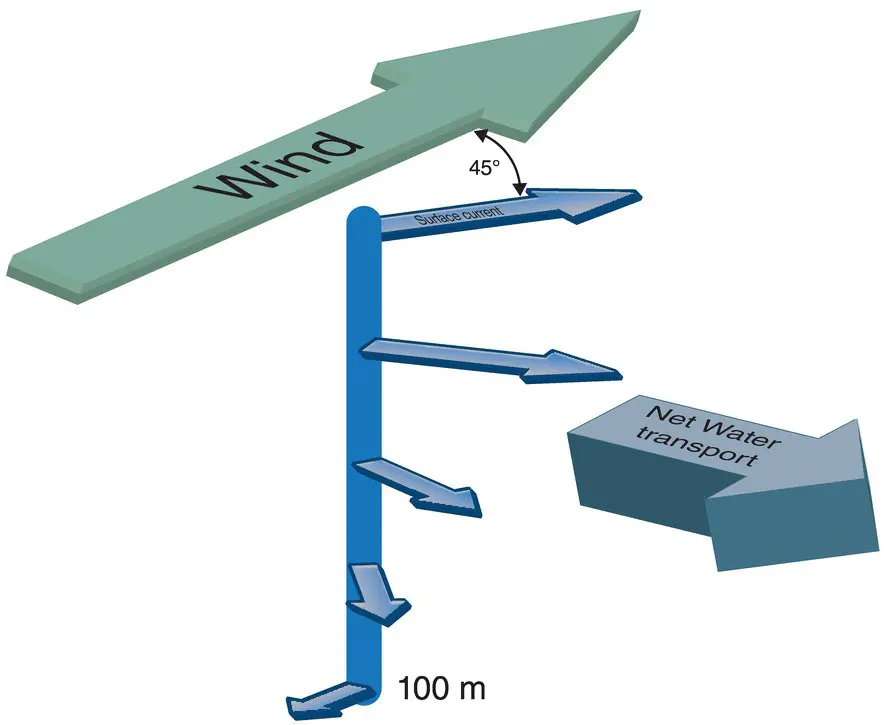

Ekman Transport is another phenomenon important to an understanding of geostrophic currents. Named for the Swedish oceanographer who first described it, and other principles, Ekman Transport is the net spiral motion down a water column created by Coriolis force and drag. Away from the surface and the direct effects of the wind, the current direction veers slightly toward the right or left with increasing depth down to about 100 m. A good way to envision this is to think of the water column as a stack of layers or playing cards, with each layer moving slightly to the right (or left in the southern hemisphere) of the layer above it ( Figure 1.9). Due to friction, current speed decreases with increasing depth so that each successively deeper layer moves more slowly than the one above. In theory the resultant net flow over the upper 100 m is at 90° to wind direction, 90° to the right of wind direction in the northern hemisphere, and 90° to the left in the southern. However, the actual net flow of the Ekman Spiral is closer to 45° in both halves of the globe.

Figure 1.8 Coriolis effect. Apparent curved path of an object not coupled to the Earth's surface, moving in the northern hemisphere.

Source: Brown et al. (1989), figure 1.2a (p. 7). Reproduced with the permission of Pergamon Press.

Figure 1.9 Ekman transport. Net spiral pattern of wind‐driven motion down through a water column due to Coriolis effect and drag. The result is a net flow 90° to the right of the wind direction in the northern hemisphere. See color plate section for color representation of this figure.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Life in the Open Ocean»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Life in the Open Ocean» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Life in the Open Ocean» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.