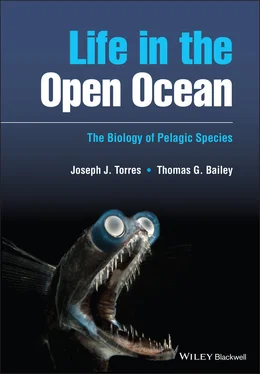

Joseph J. Torres - Life in the Open Ocean

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Joseph J. Torres - Life in the Open Ocean» — ознакомительный отрывок электронной книги совершенно бесплатно, а после прочтения отрывка купить полную версию. В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: unrecognised, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Life in the Open Ocean

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Life in the Open Ocean: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Life in the Open Ocean»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Life in the Open Ocean: The Biology of Pelagic Species

Life in the Open Ocean: The Biology of Pelagic Species

Life in the Open Ocean — читать онлайн ознакомительный отрывок

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Life in the Open Ocean», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

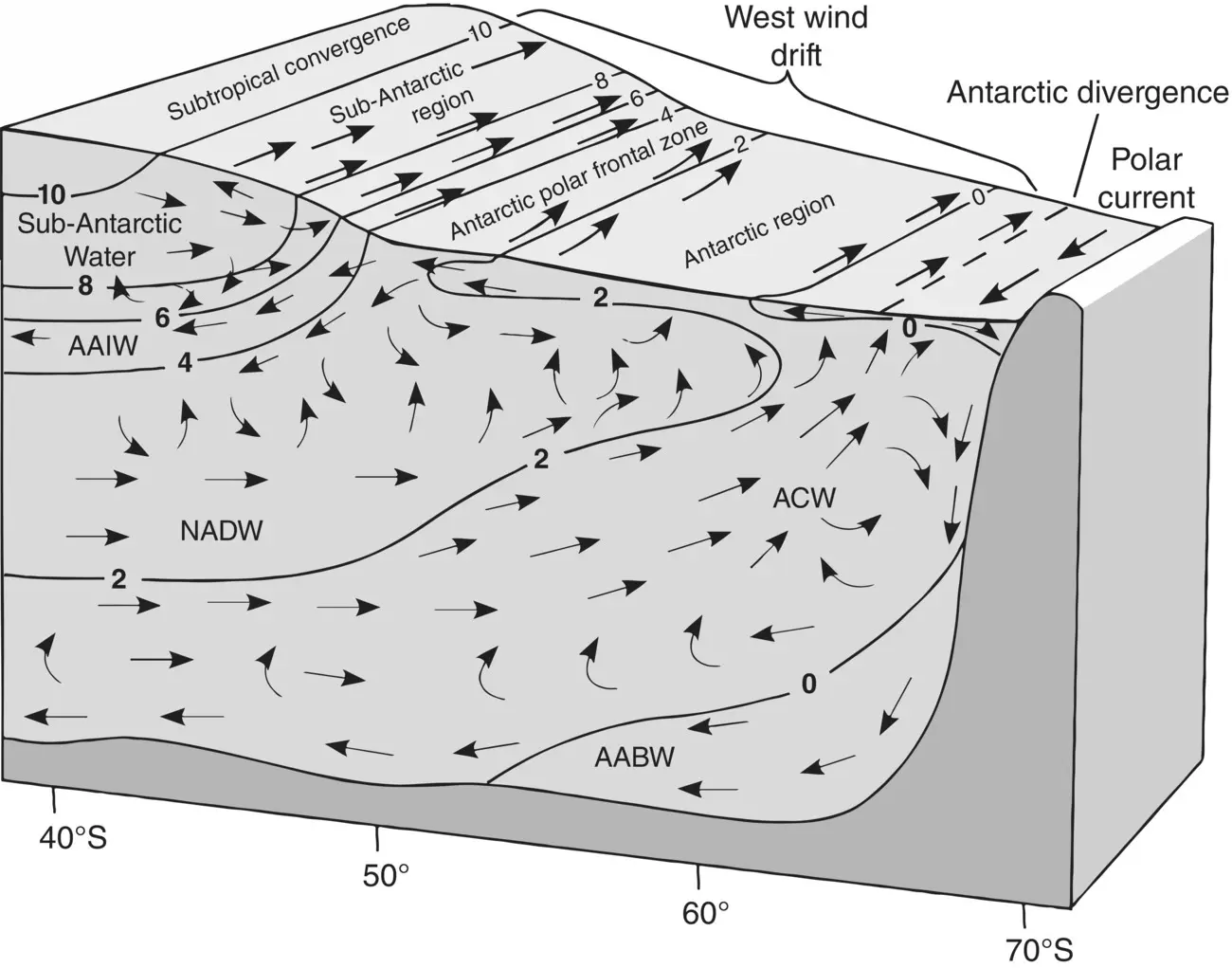

Source: Brown et al. (1989), figure 6.26 (p. 191). Reproduced with the permission of Pergamon Press.

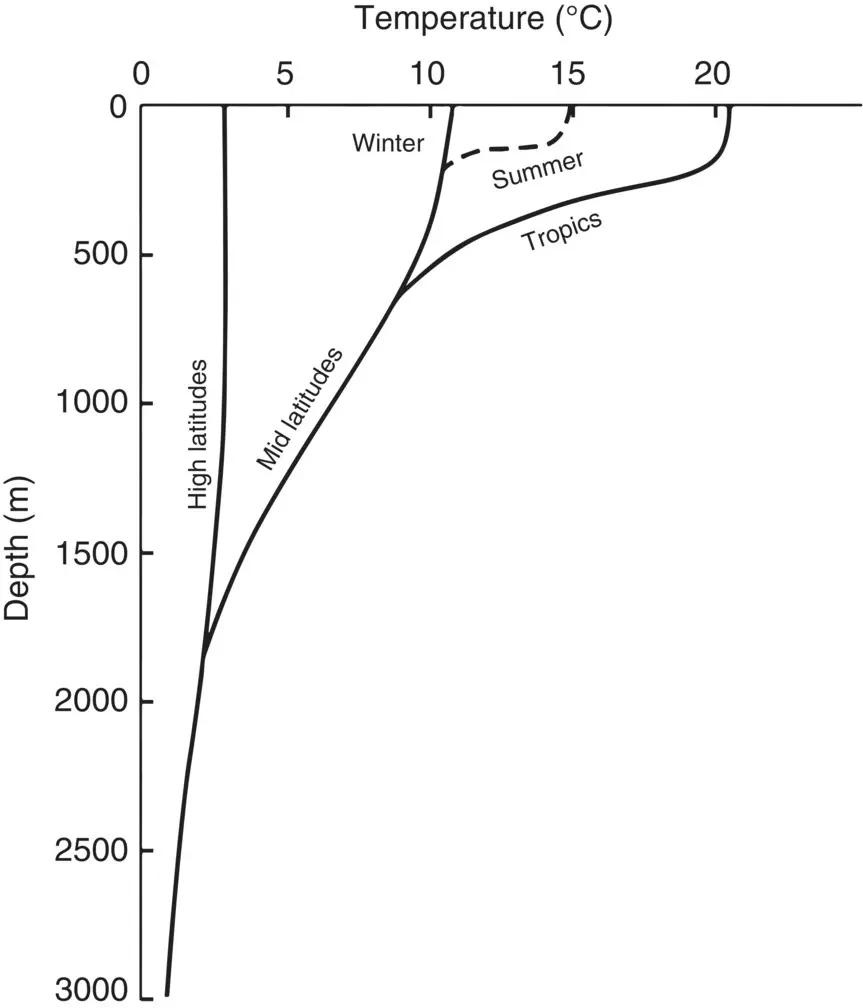

Five generic water masses are found at temperate and tropical latitudes. Surface water extends from the surface to about 200 m depth and includes the seasonal thermocline. Central water extends from just below surface water to the bottom of the permanent thermocline, usually at about 1000 m. Intermediate water resides below central water to a depth of about 1500 m, where deep water begins. Deep water is found below intermediate water but is not in contact with the bottom; it is found between 1500 and 4000 m. Deepest of the oceanic layers is bottom water, which is in contact with the seafloor.

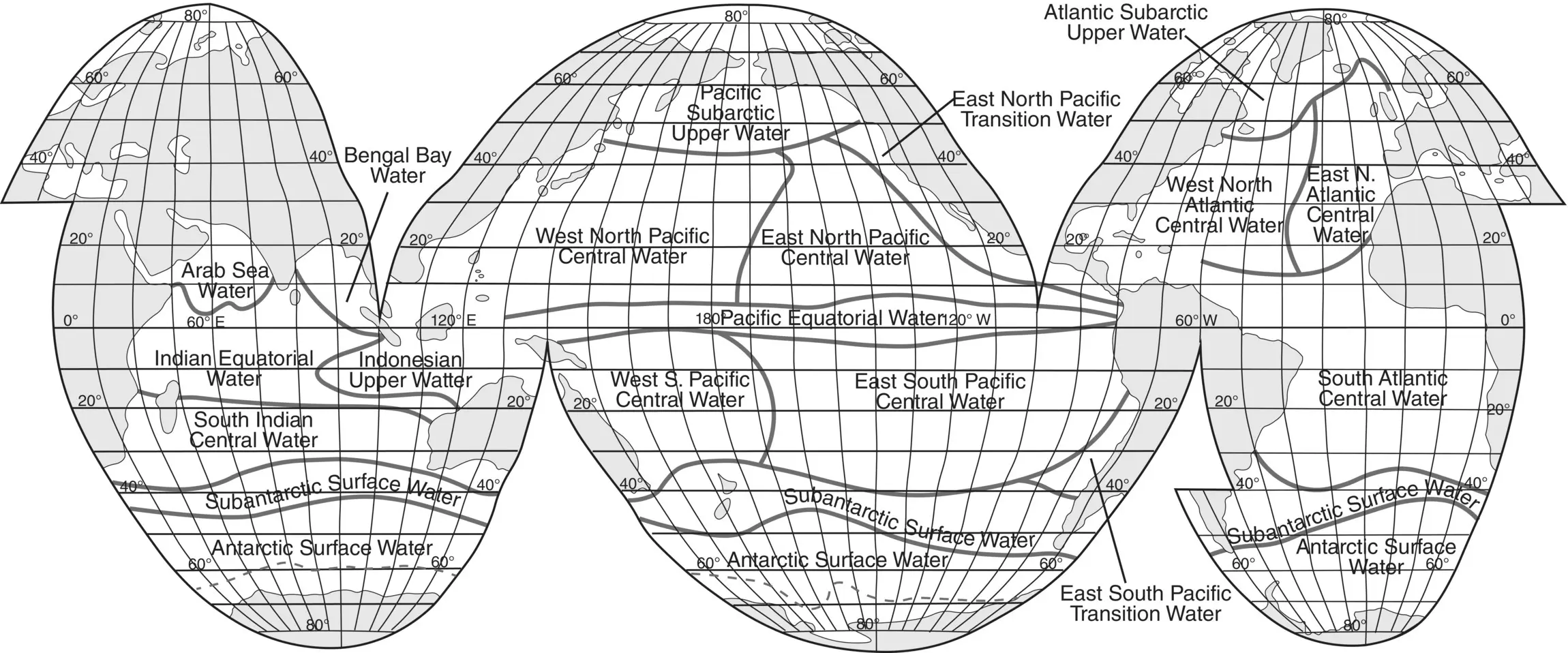

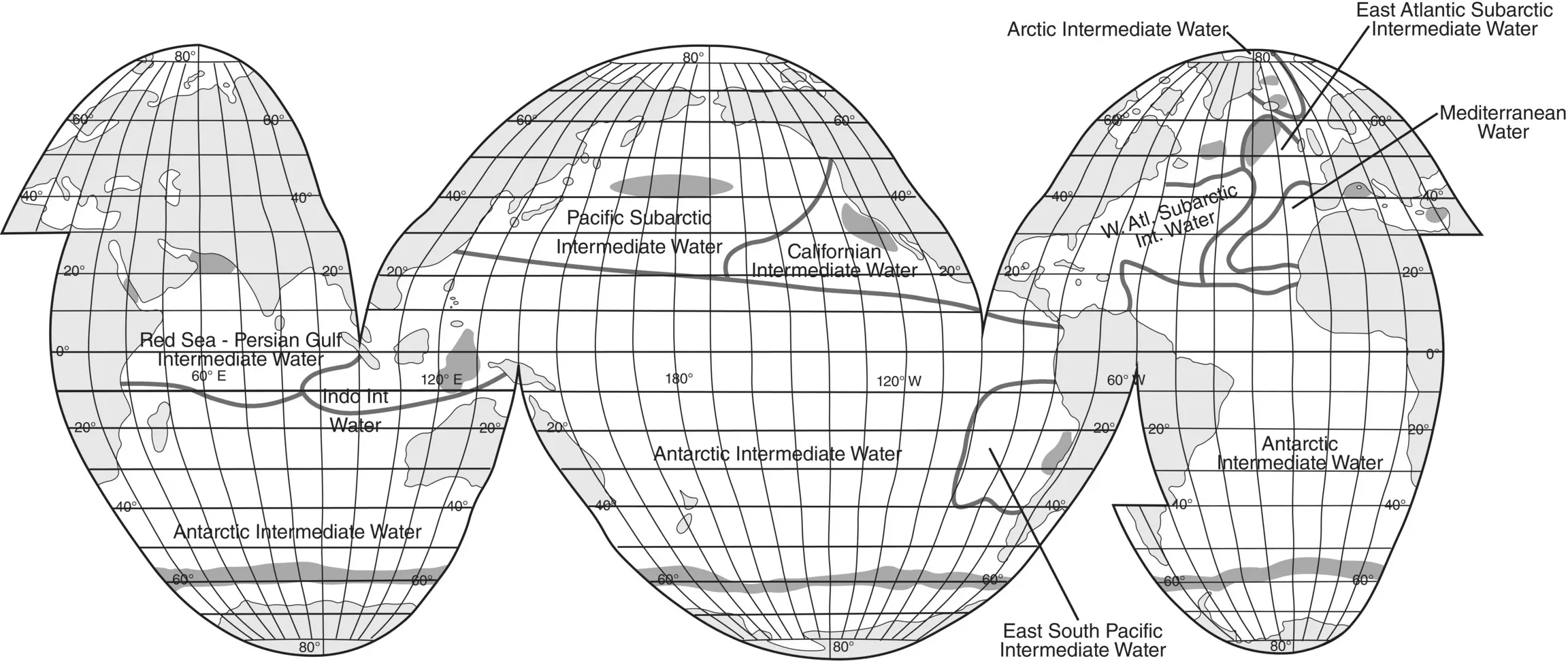

Each of the generic water masses has a large number of specific examples that can be identified by their temperature and salinity; they are named for their source region. Upper water masses (surface and central water), shown in Figure 1.13, are numerous and correspond fairly closely with surface currents. Intermediate waters are mapped in Figure 1.14. It is important to note the difference in areal extent between upper and intermediate waters. Antarctic Intermediate Water (AAIW), for example, is widespread at intermediate depths throughout the world ocean. The temperature and salinity characteristics that define AAIW (temperatures of 2–4 °C and salinities of about 34.2) provide a fairly uniform environment for the species that live within it. It is thus easy to understand why deeper‐living oceanic species are typically far more wide‐ranging than those inhabiting surface waters (Briggs 1974).

Figure 1.12 Standard depth profiles of temperature at low, middle, and high latitudes.

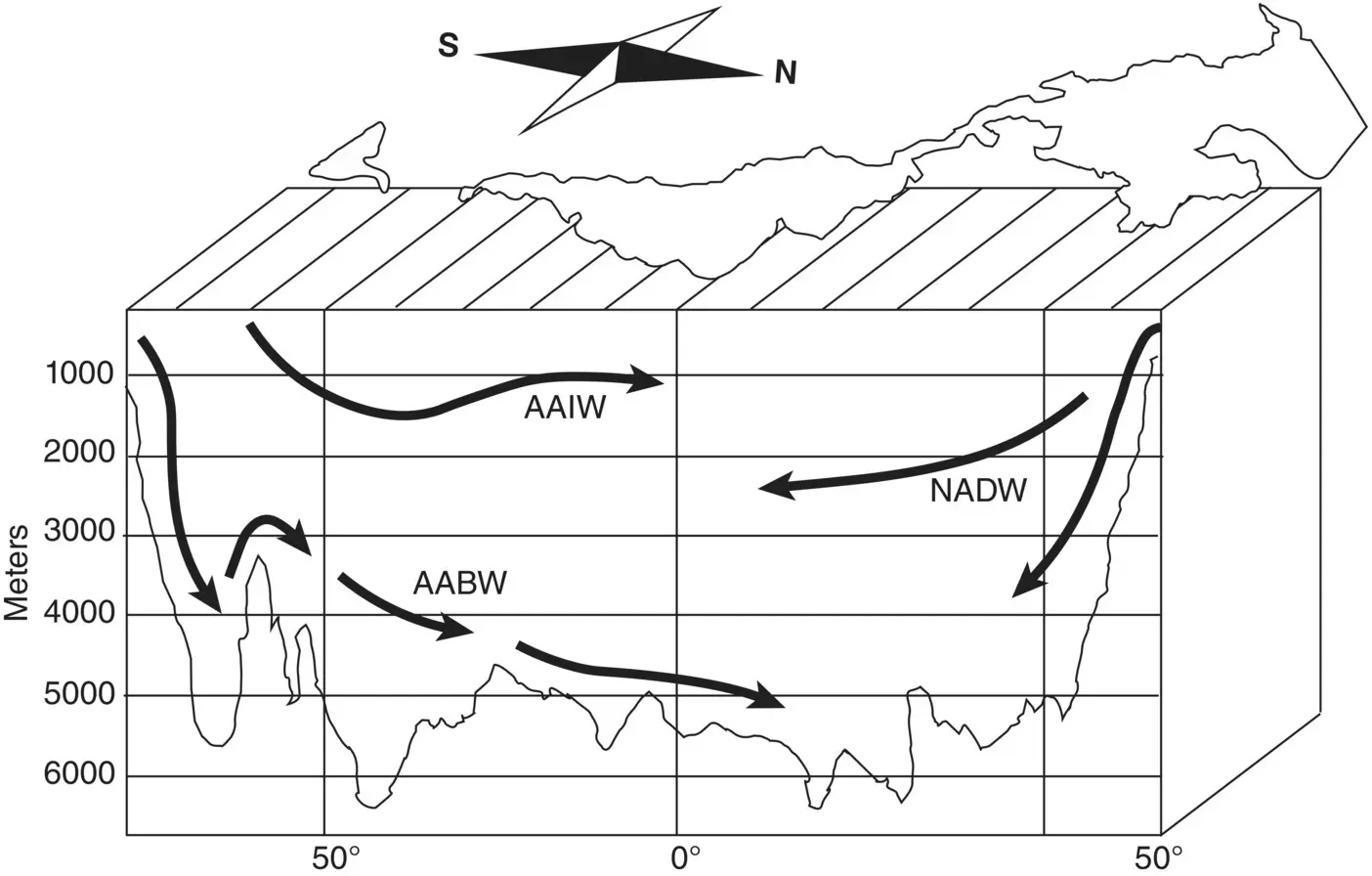

Deep and bottom water masses are even less numerous and more widespread than intermediate water masses. North Atlantic Deep Water (NADW) forms in the north Atlantic above 60 °N when cold, saline waters from the Norwegian and Greenland seas spill over the mid‐Atlantic ridge into the depths of the Atlantic ( Figure 1.15). Those waters mix with overlying water as well as water flowing south out of the Labrador Sea to create a general southward flow along the west side of the mid‐Atlantic ridge. NADW is the most important deep‐water mass in the Atlantic, extending well into the southern hemisphere.

Antarctic Bottom Water (AABW) is the most widespread of the water masses, dominating the bottom water in all three ocean basins. It is formed in winter near the Antarctic continent, mainly in the Weddell and Ross Seas, the southernmost portions of the Atlantic and Pacific Ocean basins, respectively. As discussed earlier, when ice crystals form in seawater most of the dissolved salts are excluded as brine, creating very cold and saline water. AABW is the densest water mass in the world ocean; the source water mixes very little with any less dense waters. In many areas of the Antarctic, particularly in the Ross Sea, the temperature from the edge of the continental shelf to the coast is about −2.0 °C from surface to bottom.

The Antarctic is the southern end of the line for several water masses and the mixing in the Southern Ocean is complex ( Figure 1.16). Warmer water from the north, including NADW, reaches the surface at the Antarctic divergence where it gives up its heat. Cooled water flows northward and sinks at the Antarctic Convergence, creating AAIW. The cycle of heat delivery, cooling, and sinking is the southern counterpart to the same basic process in the North Atlantic. The process at both poles is termed the thermohaline circulation or the “Great Ocean Conveyor” (Broecker 1992).

Figure 1.13 Surface and central water masses.

Source: Lalli and Parsons (1993), figure 2.13(p. 37). Reproduced with the permission of Pergamon Press.

Figure 1.14 Intermediate water masses.

Source: Lalli and Parsons (1993), figure 2.15(p. 38). Reproduced with the permission of Pergamon Press.

Figure 1.15 Deep and bottom water masses: sources and flow patterns. AAIW, Antarctic Intermediate Water; AABW, Antarctic Bottom Water; NADW, North Atlantic Deep Water.

Source: Lalli and Parsons (1993), figure 2.17(p. 39). Reproduced with the permission of Pergamon Press.

Figure 1.16 Flow patterns and mixing of water masses in the Southern Ocean. AAIW, Antarctic Intermediate Water; NADW, North Atlantic Deep Water; AABW, Antarctic Bottom Water; ACW, Atlantic Central Water.

Source: Brown et al. (1989), figure 6.20(p. 184). Reproduced with the permission of Pergamon Press.

Oxygen

Oxygen is introduced into oceanic waters (and all other waters) by diffusion from the atmosphere, aided by wind‐induced turbulence and mixing, and sometimes supplemented to a small degree by photosynthetically produced oxygen. Its solubility in water is an inverse function of salinity and temperature. Once a water mass has left the surface, its dissolved oxygen is consumed through time, mainly by microorganisms but also by larger species such as fishes and crustaceans. As a consequence, oxygen content is an indication of how long the water has been away from the surface. It is a nonconservative property of a water mass that is sometimes used as a tracer. Water masses vary substantially in their time away from the surface. At the extremes, AABW in the Pacific retains its character for 1600 years (Garrison 2002), whereas the residence time for most deep water is 200–300 years. NADW takes about 1000 years to reach the surface after sinking at the northern end of the Great Ocean Conveyor.

Regions of low oxygen concentration are termed oxygen minima ,and they vary widely in their severity. If an oceanic region includes a highly productive surface layer with large seasonal algae blooms, the bacterial oxidation of sinking organic matter may remove nearly all the oxygen from the deeper waters. Examples of such areas include the waters off the California coast, the Eastern Tropical Pacific, and the Arabian Sea. Compare the oxygen profiles from the Arabian Sea and the California Current in Figure 1.17with the profiles for the Antarctic and the Gulf of Mexico. Oxygen concentrations at the surface and at 500 m of depth in the world ocean are shown in Figure 1.18. Most of the world’s severest minima are in regions where upwelling is very strong, and algae blooms are episodically very extensive.

Oxygen minima may also occur because of topography. For example, the Black Sea and the Cariaco Basin off the coast of Venezuela have restricted communications with the rest of the open ocean because of a shallow sill restricting circulation of their deeper waters. As a consequence, their deep waters are isolated and become anoxic.

Because deeper waters have always spent some time away from the surface, an oxygen minimum of some degree is always present. However, in most places it is not severe and not limiting to animal life. In the Gulf of Mexico, for example, the oxygen drops to about 50% of surface values at a depth of 600 m, as it does in the Antarctic. In contrast, the waters off southern California drop to about 5% of surface values, and in the Arabian Sea oxygen levels drop to zero below 200 m. Such low values pose severe challenges to animal life. Moreover, oxygen minima in the Cariaco Basin and the Black Sea include the presence of sulfides, which are metabolic poisons. How animals cope (or not) with such low levels of oxygen will be covered in the next chapter.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Life in the Open Ocean»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Life in the Open Ocean» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Life in the Open Ocean» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.