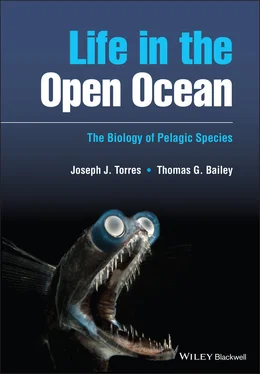

Joseph J. Torres - Life in the Open Ocean

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Joseph J. Torres - Life in the Open Ocean» — ознакомительный отрывок электронной книги совершенно бесплатно, а после прочтения отрывка купить полную версию. В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: unrecognised, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Life in the Open Ocean

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Life in the Open Ocean: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Life in the Open Ocean»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Life in the Open Ocean: The Biology of Pelagic Species

Life in the Open Ocean: The Biology of Pelagic Species

Life in the Open Ocean — читать онлайн ознакомительный отрывок

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Life in the Open Ocean», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

Geostrophic currents are the result of a dynamic balance between the driving force of the wind, the turning effects of the Coriolis force, and pressure gradients caused by differences in sea‐surface height. Ekman Transport and wind stress act to create a slight hill of water, or topographic high, roughly in the middle of a gyre. Water in the high attempts to flow downhill but is offset by the Coriolis force so that the current in the gyre becomes parallel to the elevated sea surface, flowing clockwise in the northern hemisphere and counterclockwise in the southern.

Ocean Gyres and Geostrophic Flow

Six great circuits are found in the world ocean, four in the southern hemisphere (South Atlantic, South Pacific, Indian, and Antarctic Circumpolar) and two in the northern (North Atlantic, North Pacific). The gyres correspond fairly well to the biogeographic distribution of oceanic species.

With the exception of the Antarctic Circumpolar Current (ACC), which is not technically a gyre since it flows uninterrupted around the Antarctic continent, all gyres flow around the continental margins ( Figure 1.5). The circuits are bounded on the east and west by eastern and western boundary currents and on the north and south by transverse currents. The Gulf Stream in the North Atlantic is an excellent example of a western boundary current and the Canary Current, along west Africa, of an eastern boundary current. Partly because of the convergence of the westerly winds, western boundary currents are far stronger and more clearly defined than their counterparts in the east. Additional contributors to the greater strength of western boundary currents are the fact that the “hill of water” at the heart of the geostrophic circulation is displaced to the west by the eastward rotation of the Earth, creating a steeper pressure gradient and a stronger poleward flow of water. The phenomenon is termed “westward intensification.” Table 1.2gives a comparison of the characteristics of eastern and western boundary currents.

Upwelling

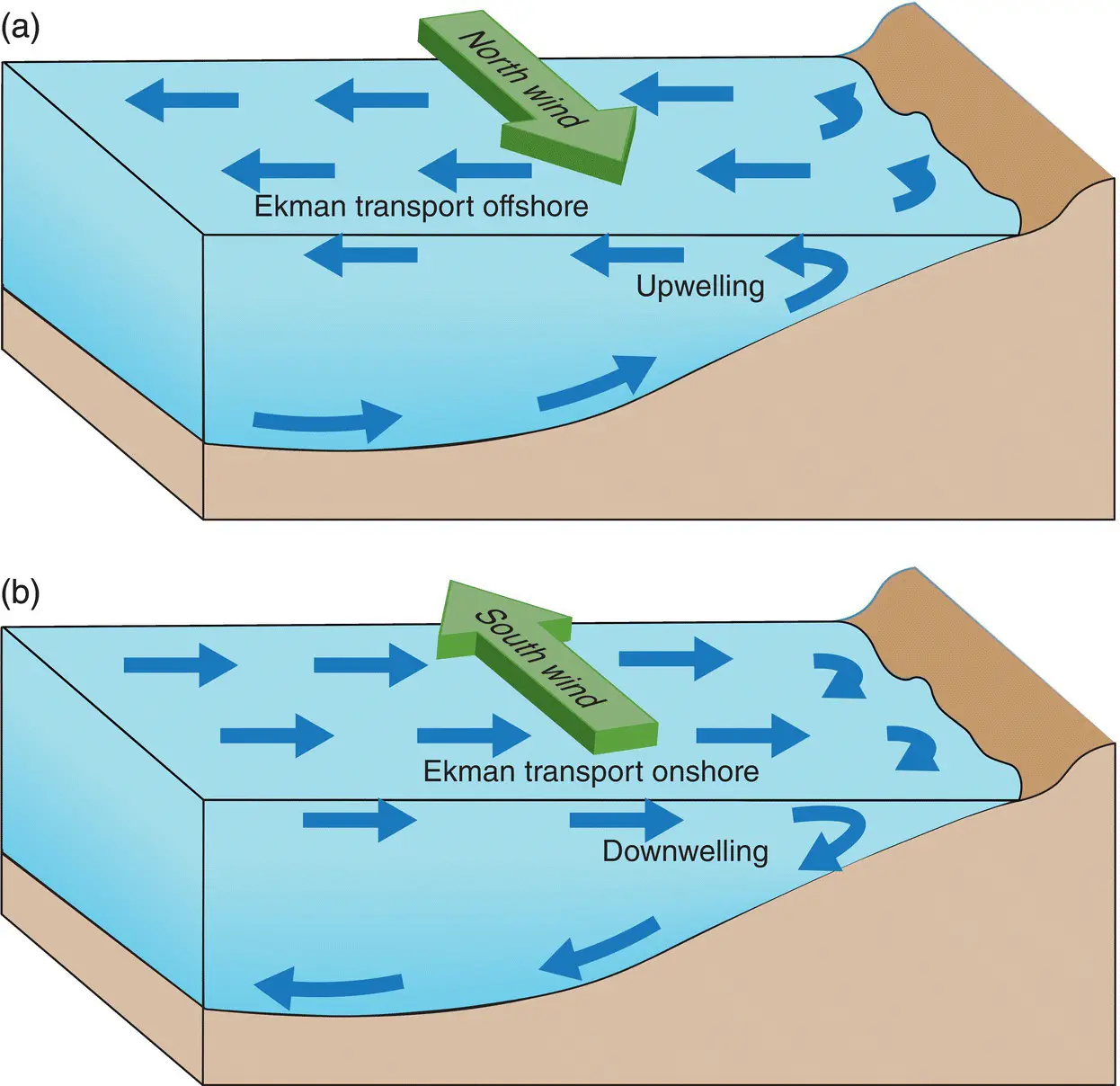

Wind‐driven movement of water can also induce vertical circulation, particularly in coastal regions. On the west coasts of land masses in the northern hemisphere, winds out of the north or northwest cause along‐shore water movement, which is moved offshore (clockwise) by Ekman transport. In the southern hemisphere, winds from the south will result in similar coastal upwelling. The water moved offshore is replaced by cooler, nutrient‐laden water welling up from below ( Figure 1.10), resulting in an ideal situation for increased productivity. Upwelling regions are the most fertile oceanic areas of the world, often supporting large fisheries for small coastal pelagic fishes such as sardines and anchovies. As we will see later, areas of high ocean productivity are often associated with zones of low oxygen at mid‐depths, resulting from the biological degradation of sinking particulates in a stratified water column. Upwelling can also occur offshore, which it consistently does at the equator where the north and south equatorial currents meet and at the Antarctic divergence. Downwelling, the opposite situation, occurs when winds and Ekman transport cause surface water to converge along a coast.

Deep‐Ocean Circulation

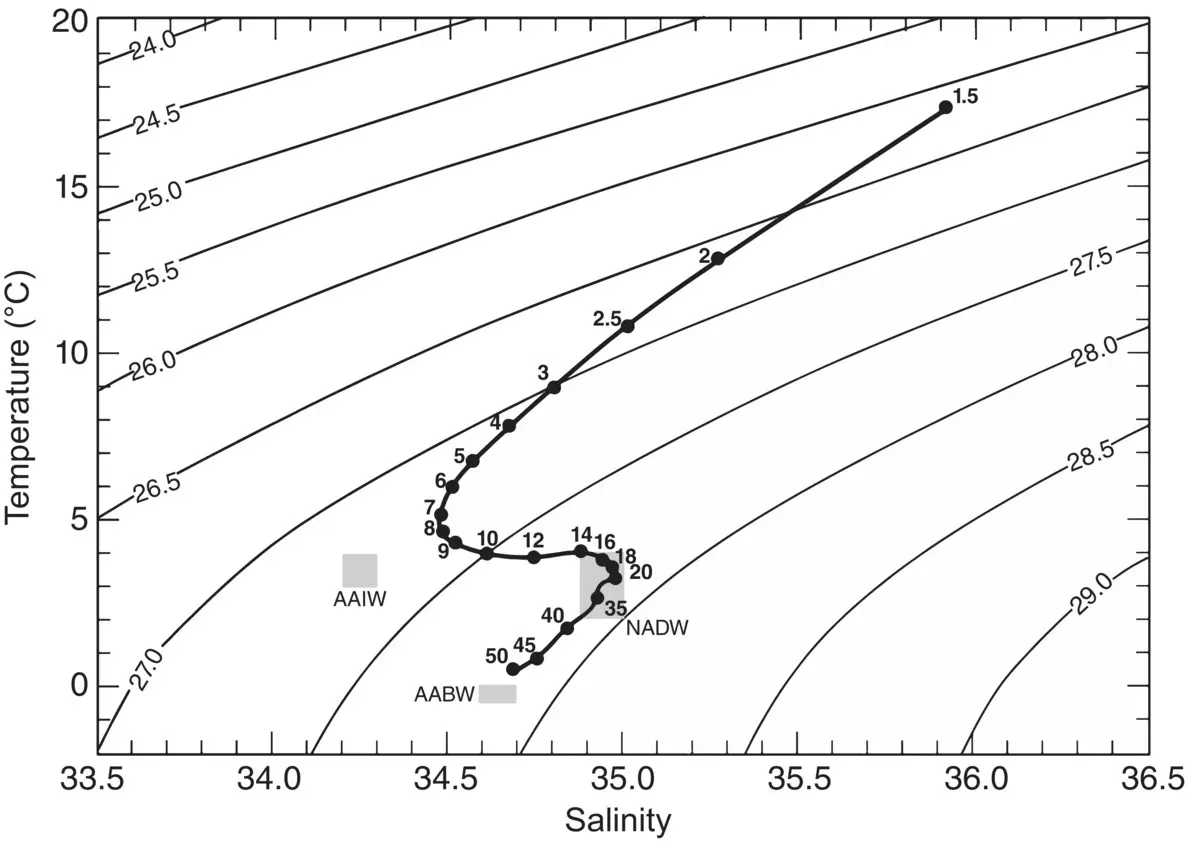

Oceanic waters are stratified by density, which is mainly a function of salinity and water temperature. The colder or saltier a parcel of water is, the greater its density. Temperature–salinity plots, or T‐S diagrams, help characterize ocean layering and water‐column characteristics. Figure 1.11, a T‐S curve for an oceanographic station in the Atlantic, is an example. Note that the lines of equal density, or isopycnals, each comprise a variety of temperatures and salinities; the same density can result from many different temperature–salinity combinations.

Vertical structure in the ocean can be divided into three density zones: an upper mixed layer, a layer of changing density, and the deep layer.

The upper mixed layer is a region of fairly uniform density because of the action of wind mixing, waves, and currents. Depending on place and season, it can vary from being very shallow (<30 m) to depths of greater than 200 m and is the only region of the ocean that interacts with the atmosphere. The upper mixed layer contains about 2% of the volume of the ocean.

Beneath the upper mixed layer is the pycnocline, where density increases rapidly with depth and the increasing density acts as a barrier between the upper and deep layers. If declining temperatures are mainly responsible for the increasing density, the pycnocline is also a thermocline. If salinity is the major cause, it is a halocline. The pycnocline extends from the bottom of the mixed layer to the cold and stable deep zone. In most regions of the world ocean, the pycnocline ends at about 1000 m of depth and contains about 18% of the world ocean volume.

Table 1.2 Boundary currents in the Northern Atlantic and Pacific Oceans. Data from Gross (1990), Schwartzlose and Reid (1972), Sverdrup et al. (1942), Zhou et al. (2000).

| Location | Current | Speed (cm s −1) | Transport (sv a) | Common features | Special features |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Western Atlantic | Gulf Stream | 120–140 | 55 | Narrow (100–150 km) and deep (2 km) | Sharp boundary with coastal circulation system; little or no coastal upwelling; waters tend to be depleted in nutrients, unproductive |

| Western Pacific | Kuroshio Current | 89–180 | 65 | ||

| Eastern Atlantic | Canary Current | 10–15 | 16 | Broad (~1000 km) and shallow (<500 m) | Diffuse boundaries separating from coastal currents; coastal upwelling common |

| Eastern Pacific | California Current | 12.5–25 | 10 |

asv = sverdrup (1 sv = 1 million cubic meters per second)

Figure 1.10 Upwelling and downwelling. (a) Ekman transport caused by wind blowing from the north moving surface water offshore, results in deeper water upwelling to the surface in the northern hemisphere. (b) Ekman transport due to winds blowing from the south moves surface water onshore and subsequently down slope.

In the cold and relatively stable deep zone, temperature varies very little with depth and density increases only gradually. The deep zone contains the remaining 80% of the global ocean at depths greater than 1000 m, well away from surface influences.

Water Masses

The global ocean has a variety of different water masses, parcels of ocean identifiable by their temperature, salinity, and density characteristics that determine their place within the vertical structure of the oceanic water column. It is important to keep in mind that certain properties of a water mass are determined during its sojourn at the surface, e.g. temperature and salinity. Those are conservative properties and are changed only when a water mass mixes with another. In the deep ocean, water masses can mix only when their densities are roughly equal, otherwise they remain stratified. Therefore vertical movements of water, away from or toward the surface, require a weakly stratified water column, such as is found near the poles. Figure 1.12is a standard diagram of oceanic temperatures at depth at low, middle, and high latitudes.

Figure 1.11 T‐S diagram. Temperature–salinity plot from an oceanographic station in the Atlantic. The axes represent salinity ( X ) and temperature ( Y ). The curved lines represent isopycnals (equal density). AAIW, Antarctic Intermediate Water; NADW, North Atlantic Deep Water; AABW, Antarctic Bottom Water.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Life in the Open Ocean»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Life in the Open Ocean» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Life in the Open Ocean» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.