Joseph J. Torres - Life in the Open Ocean

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Joseph J. Torres - Life in the Open Ocean» — ознакомительный отрывок электронной книги совершенно бесплатно, а после прочтения отрывка купить полную версию. В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: unrecognised, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Life in the Open Ocean

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Life in the Open Ocean: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Life in the Open Ocean»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Life in the Open Ocean: The Biology of Pelagic Species

Life in the Open Ocean: The Biology of Pelagic Species

Life in the Open Ocean — читать онлайн ознакомительный отрывок

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Life in the Open Ocean», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

(1.6)

which you may recognize as the “fluid equivalent” of the expression for momentum. In fact, drag is the removal of momentum from a flowing fluid.

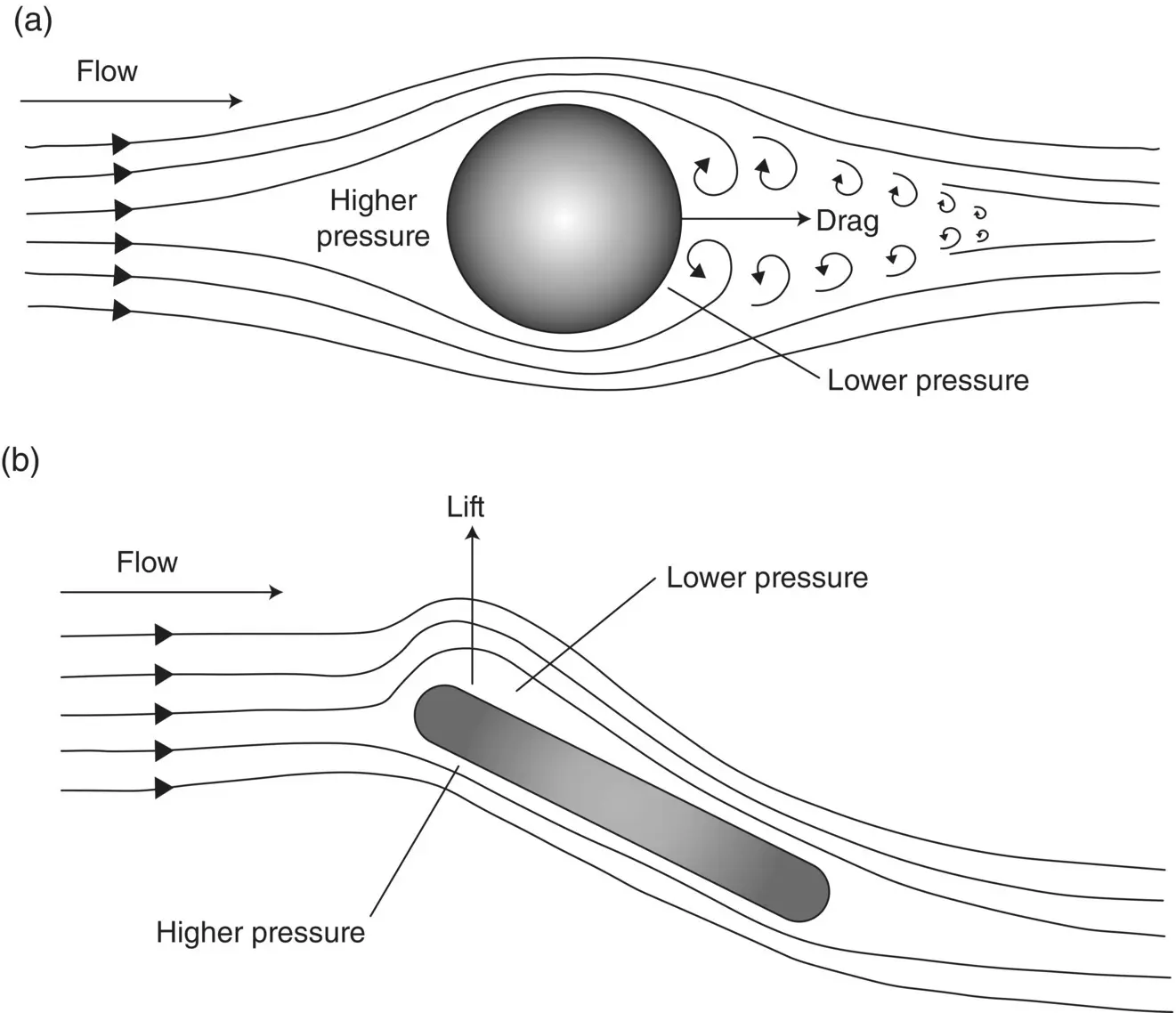

All swimming species experience drag as they swim. At low Reynolds numbers, usually in smaller species swimming at slower speeds, friction drag is the more important force. At higher Re, pressure drag is more important. Because drag is difficult to measure and more difficult to predict from theory, total drag is most often used to describe the drag force, without discriminating between friction and pressure drag.

Total drag depends on three elements. The first is the dynamic pressure, as expressed earlier, which itself is a function of the velocity of the fluid and its density. The second is the size of the object in the flow since pressure is a force per unit area. The third is the shape of the object in the flow.

Figure 1.3 Flow‐induced differential pressure. (a) Drag. (b) Lift.

Size can take a few different forms. The most common is the frontal, or the maximum cross‐sectional area of the object in the flow. It can also be the total area of the object in the flow or the wetted surface area. When giving a value for drag, the way size has been expressed is quite important.

The way drag force behaves with different shapes in a flow regime cannot be predicted from first principles except for the simplest shapes, such as a sphere. Instead, drag force must be measured empirically to create a fudge factor known as the drag coefficient or C d. The drag coefficient in turn depends on the character of the flow regime itself, which is represented by the Reynolds number. So drag is represented by the equations

(1.7)

and

(1.8)

The difficulty of predicting how drag behaves for different shapes in a flow is a real problem for those interested in estimating the cost of overcoming drag to swimming species. You cannot just look up a C dfor your target species unless you happen to be very lucky. Usually you have to use the next best thing, which is a value determined for the closest shape you can find (see e.g. Batchelor 1967).

Temperature

As a factor governing the distribution of open‐ocean species, temperature is huge. By far, most pelagic species are ectotherms: their internal temperature matches that of their environment. All invertebrates and all but a very few species of fishes are ectotherms. Because of their internal biochemistry, ectothermic species have a range of temperatures that is optimal for their survival and that in turn dictates their range, or distribution, within the open‐ocean ecosystem. In contrast, marine mammals and seabirds are endotherms: they produce and maintain their own body heat. Endothermy confers some independence from the tyranny of ocean temperature. Many species of marine mammals, particularly the great whales, range over huge distances and experience swings from polar to tropical temperatures each year. A few species of fishes, notably the tunas and mackerel sharks, are regional endotherms or heterotherms: capable of trapping the heat produced in their swimming muscle by using a heat exchanger in their circulatory system. The temperature within the muscle reaches temperatures rivaling that of mammals, allowing regional endotherms to be quite effective swimmers indeed.

Temperature in the ocean varies predictably in both the horizontal (latitude and longitude) and vertical (depth) planes. However, to understand why temperature varies with depth and latitude in the way that it does, we need to know a little about ocean circulation. In turn, to understand ocean circulation, we need to have a clear mental picture of the geography of the ocean basins.

Table 1.1 Characteristics of the ocean basins.

| Ocean | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Atlantic | Arctic | Indian | Pacific | Southern | |

| Ocean area (10 6km 2) | 82.22 | 14.06 | 73.48 | 165.38 | 20.33 |

| Mean depth (m) | 3600 | 1117 | 3963 | 4200 | 4000–5000 |

| Maximum depth (m) | 9560 | 4440 | 7725 | 11 034 | 7235 |

| Location of maximum depth | Puerto Rico Trench | Eurasia Basin | Java Trench | Marianas Trench | South Sandwich Trench |

The Oceans and Ocean Basins

Since the year 2000, when the Southern Ocean gained official status from the International Hydrographic Organization, the Earth has had five officially recognized major oceans: The Arctic Ocean, The Atlantic Ocean, The Indian Ocean, The Pacific Ocean, and the Southern Ocean. Vital statistics for the five oceans are given in Table 1.1.

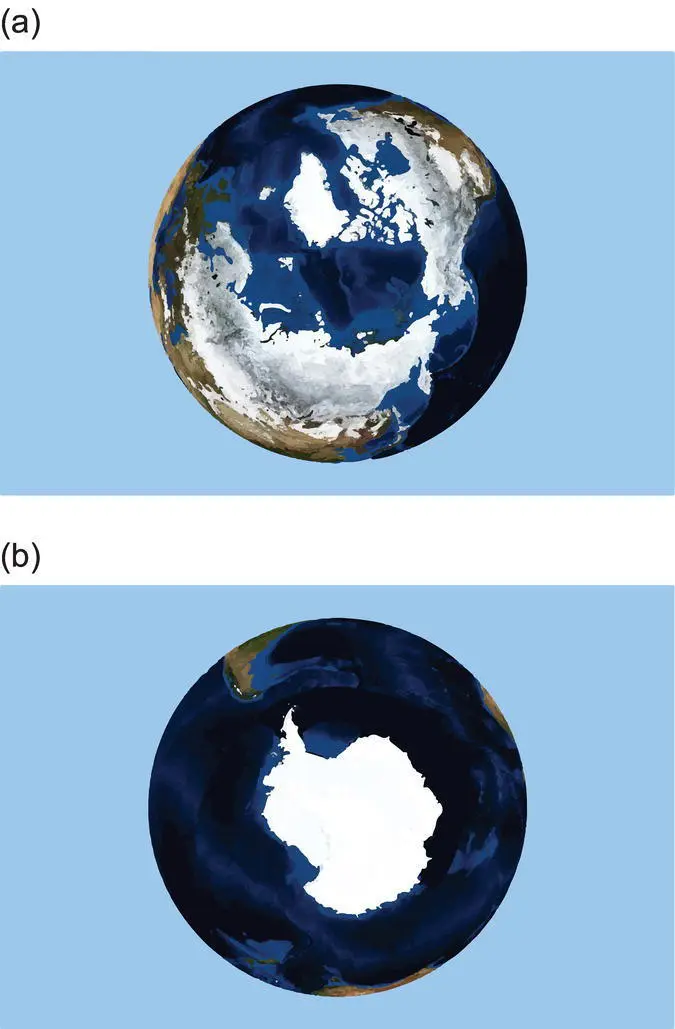

The largest and deepest ocean basin is the Pacific, whose sheer vastness really requires a globe to appreciate. The Atlantic and Indian Oceans, each somewhat less than half the size of the Pacific, follow in size. The two polar oceans, the Southern and Arctic, are the smallest. The Southern Ocean, extending from a latitude of 60° south to the Antarctic Continent, comprises the southernmost portions of the Pacific, Atlantic, and Indian Oceans, which is why it was only recently officially recognized as an Ocean in and of itself. It is worth mentioning here that the Arctic and Antarctic are fundamentally quite different. Both are quite cold, of course, and sea ice plays a large role in the ecology of each. However, the Antarctic is a land mass surrounded by ocean, whereas the Arctic is an ocean surrounded by land ( Figure 1.4a and b).

The continents define the boundaries of the ocean basins. Within each of the basins, a characteristic circulation transports large quantities of water with all the elements that such bodies of water contain, including plants, animals, gases, salt, and heat. Energy for the water movement is provided by the radiation of the Sun and the rotation of the Earth. The Sun’s heat drives circulation within the atmosphere, producing the Earth’s prevailing wind patterns that in turn drive surface ocean circulation. Deep ocean circulation, which has a more profound vertical component, is driven by changes in seawater density. Cooler or more saline water will sink below a warmer or less saline body of water. Since the density of seawater is determined by its temperature and salinity, solar radiation ultimately is responsible for deep‐ocean circulation as well. Latitudinal gradients in temperature cause heat loss or gain across the ocean–atmosphere interface. Changes in salinity result from evaporation, precipitation, and in polar regions from the freezing and melting of sea ice. An understanding of the influence of the Earth’s rotation on ocean circulation is less intuitive; that influence is described in the next section.

Figure 1.4 The Polar Oceans. (a) Arctic Ocean basin. (b) Southern Ocean surrounding Antarctica.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Life in the Open Ocean»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Life in the Open Ocean» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Life in the Open Ocean» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.