Joseph Roth

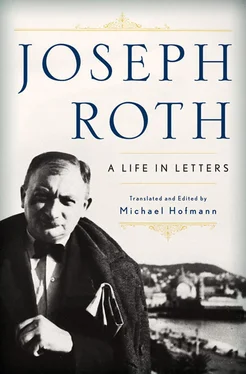

Joseph Roth: A Life in Letters

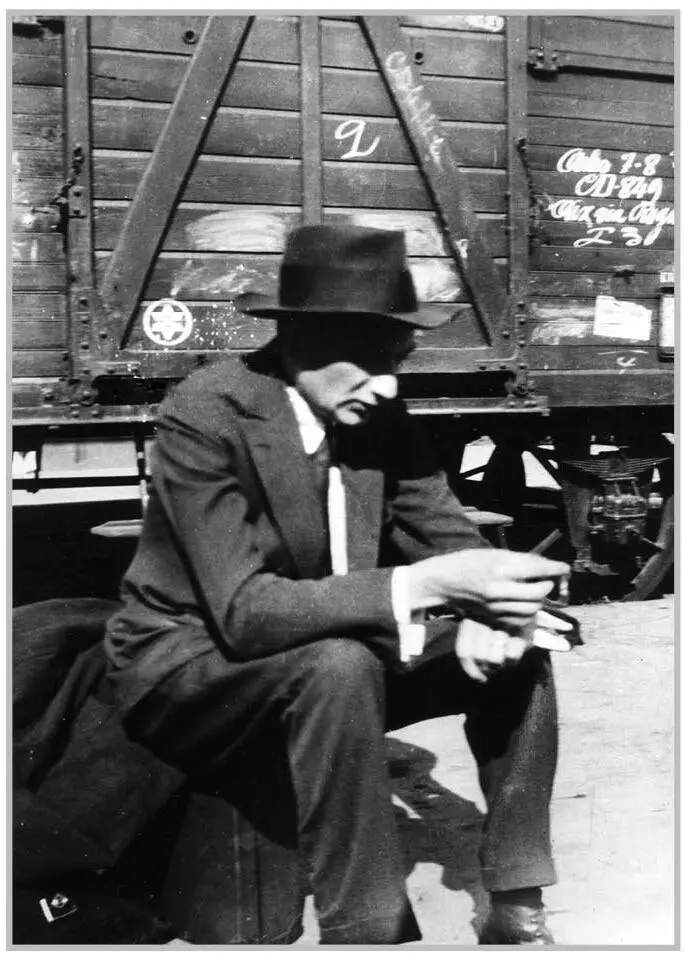

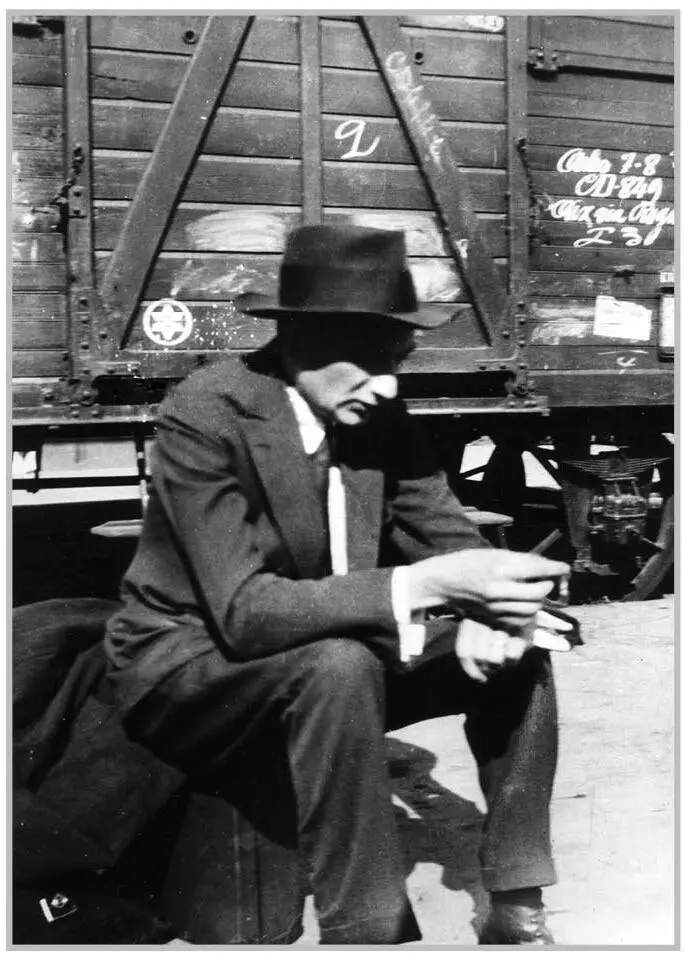

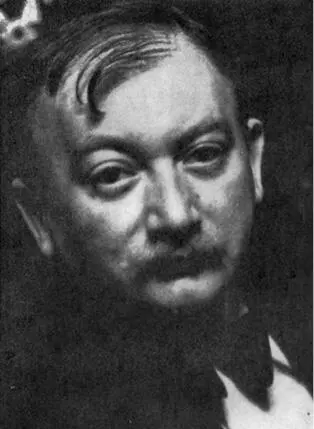

Frontispiece: Joseph Roth on a railway platform, somewhere in France, in 1925.

Joseph Roth: A Life in Letters

For my friend Rosanna Warren

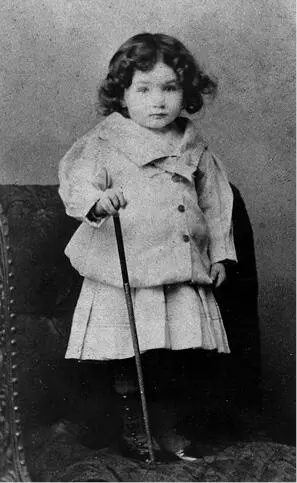

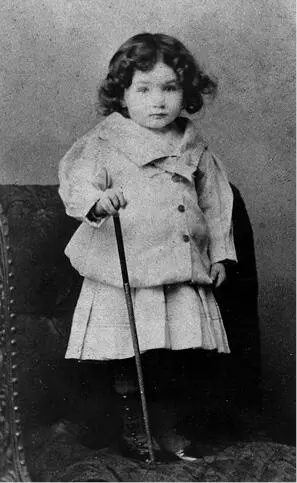

Joseph Roth, age three

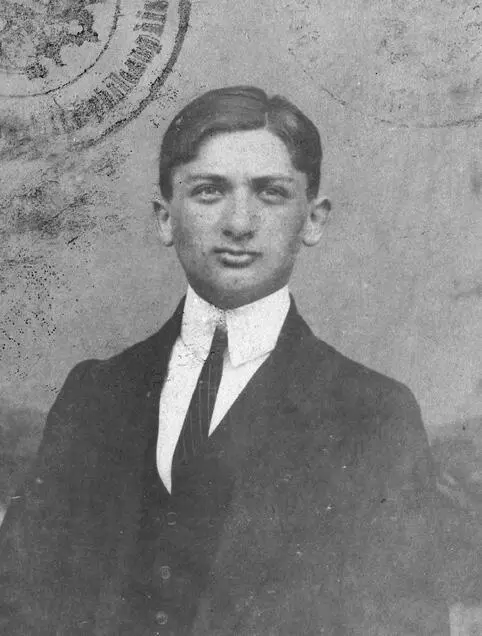

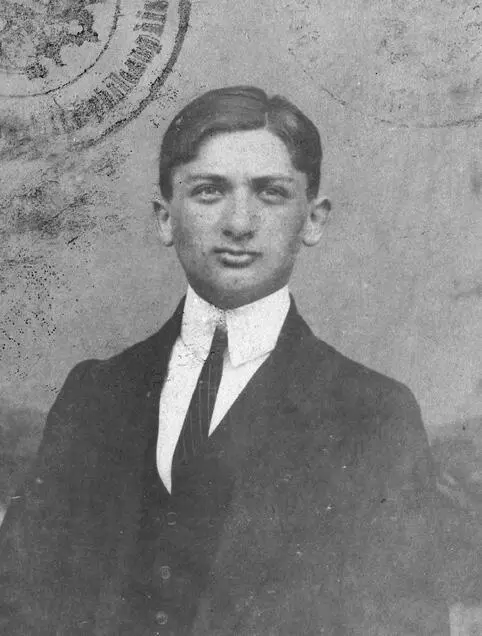

Joseph Roth’s student ID at the University of Vienna

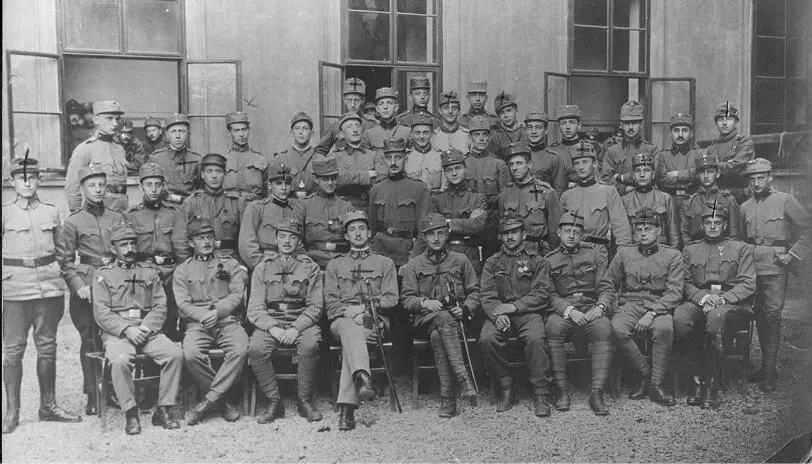

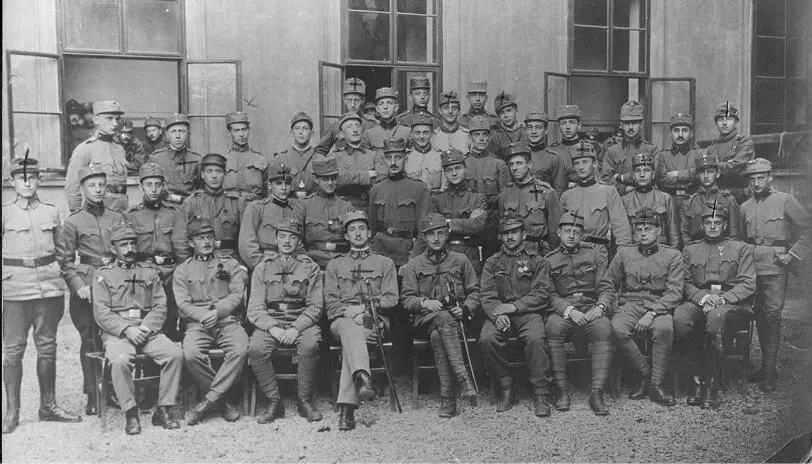

Joseph Roth’s military training company

Friedl Roth with dog

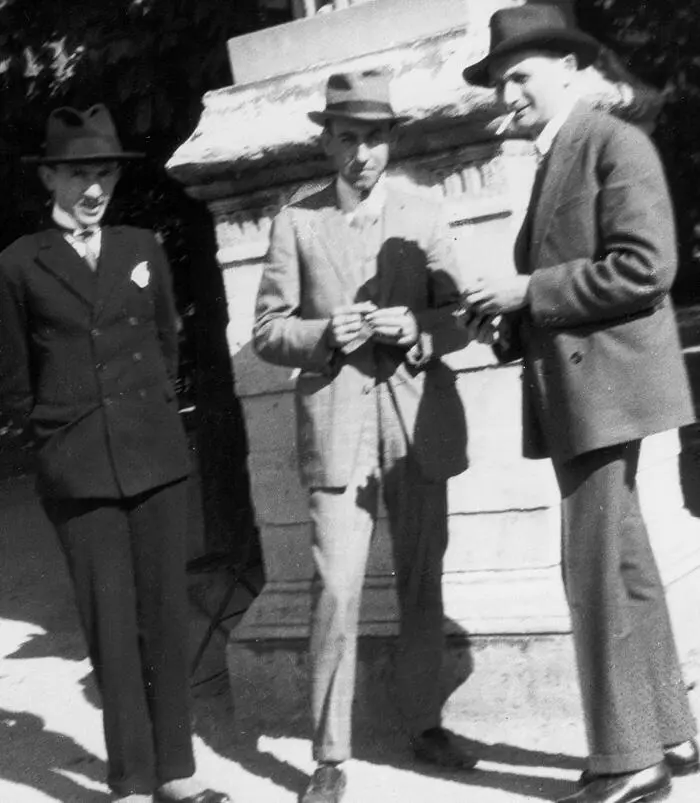

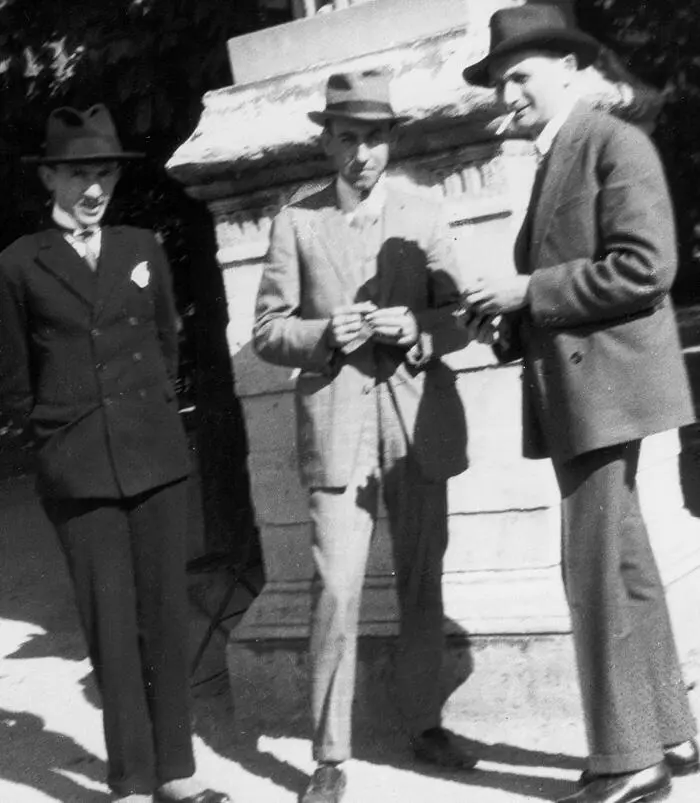

Joseph Roth in Paris, with two friends from Brody

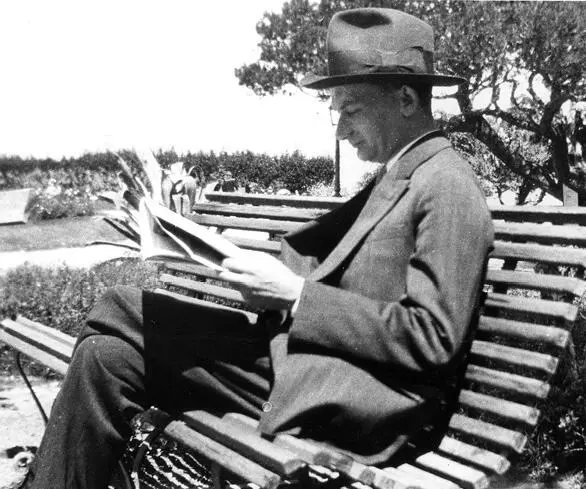

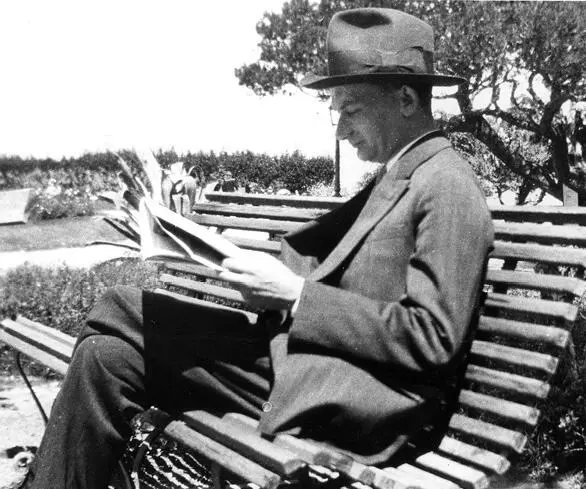

Joseph Roth with the trademark newspaper

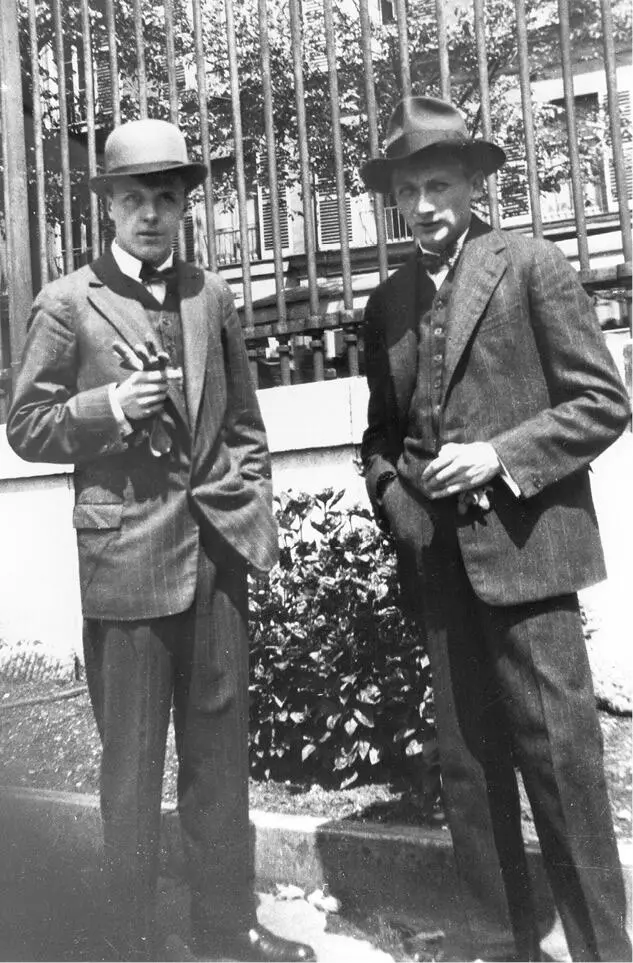

Joseph Roth with Heinrich Wagner

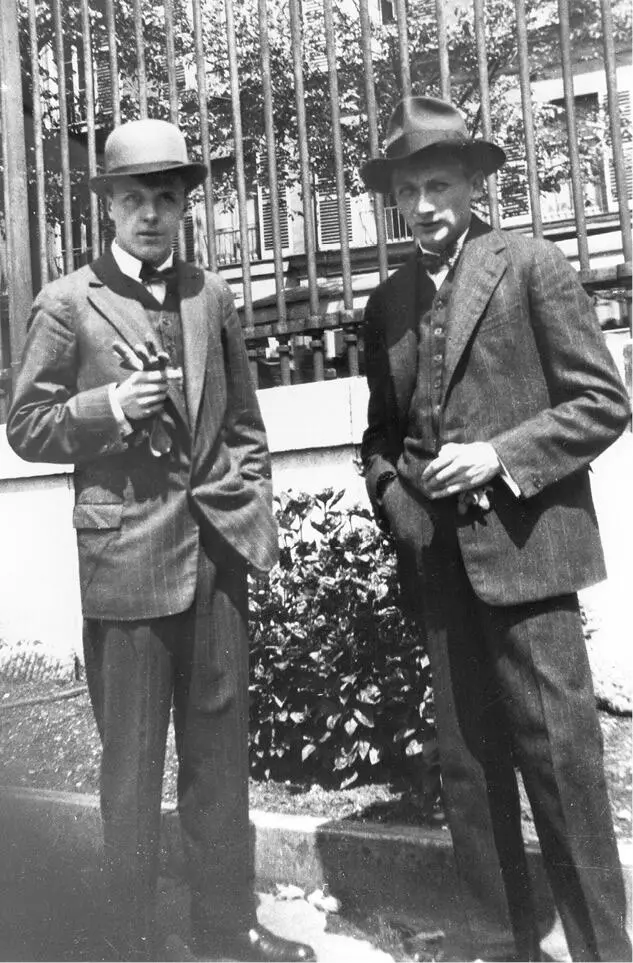

Joseph Roth with Bernard von Brentano in the Jardin du Luxembourg, Paris

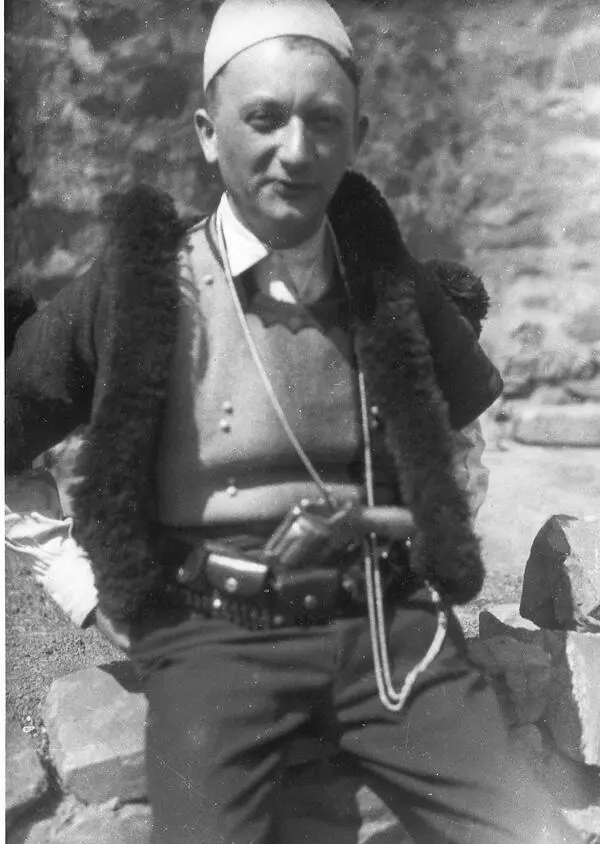

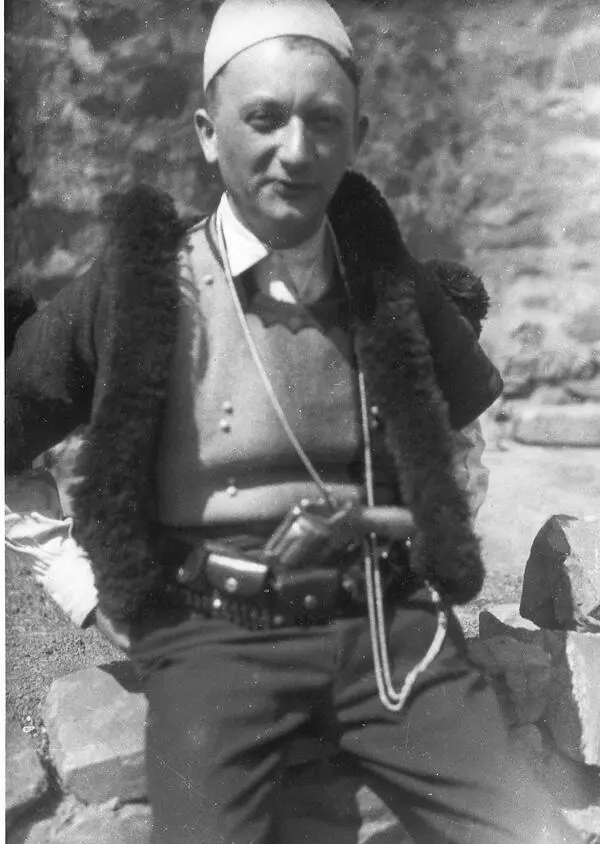

Joseph Roth in Albanian folkloric costume, in 1927 in Albania

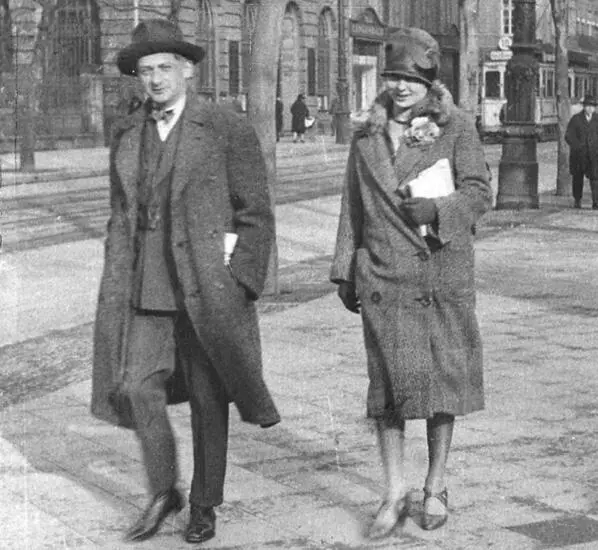

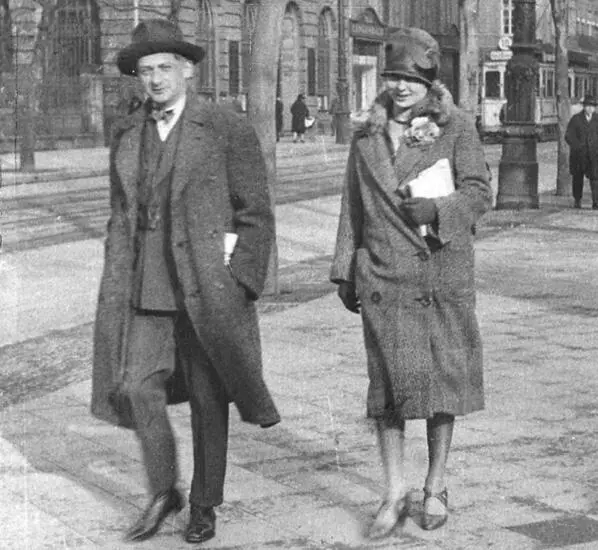

Joseph Roth with Friedl in Berlin, in 1922

Joseph Roth with Paula Grübel and a friend

Joseph Roth in the company of Dutch writers in a café in Amsterdam in 1937

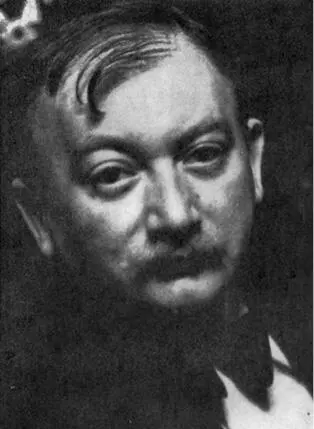

A signed portrait of Joseph Roth

Nothing to parents (but Joseph Roth never saw his father, Nahum, who went mad before he knew he had a son, and reacted to his overproud and overprotective mother, Miriam, or Maria, to the extent that he sometimes claimed to have her pickled womb somewhere). Nothing to his wife (poor, bewitching Friedl Reichler, who after six years of a restless, oppressive, and pampered marriage disappeared into schizophrenia, and left him to make arrangements for her, and pay for them, and wallow in the guilt and panic that remained). Nothing to the lovers and companions of his last years — the Jewish actress Sibyl Rares, the exotic half-Cuban beauty Andrea Manga Bell, the novelist Irmgard Keun, his rival in cleverness and dipsomania — nothing to perhaps his very best friends (with such a protean, or polygonal character as Roth’s, who contrived to present a different aspect of himself to everyone he knew, it’s hard to tell for sure) — Stefan Fingal, Soma Morgenstern, Joseph Gottfarstein. Except to family, very few — initially, I had the sense, none at all — in the intimate Du form, and most of those there are, ironically, to near-strangers, because they had served, as he had, briefly, in the Austrian army, where it was form to address a brother officer, even if one didn’t know him from Adam, as Du . Very few early — barely a dozen before 1925, when Roth, thirty, a married professional, a published novelist, and an experienced vagrant already on to his third country and maybe his fourth newspaper, gets his big break as a journalist, in Paris, for the liberal Frankfurter Zeitung . Very little explicitly or frontally about aesthetics, ambition, writing, shop (references to the novels, when he does talk about them, are so grudgingly or airily unspecific, it’s often impossible to be sure which one of them he’s talking about). Little in the way of chat, description, narrative, confession, or scandal — this was a man with books to write, and columns to fill.

So why read them? If they have little bearing on his literary output, and are not even addressed to the people who mattered most in his life? Well, to get a sense, first of all, and in the absence of a biography in English, of the stations of the man’s life, his classic westward trajectory (like that of Flight Without End or The Wandering Jews ) from the Habsburg crown land of Galicia just back of the Russian border, on the edge of Europe if not of the civilized world, in quick, brief stages to Vienna, to Berlin and Frankfurt, and then to Paris — a sort of schizoid Paris, first (in 1925) the paradisal place of the fulfillment of hopes and dreams, and then, after 1933, the locus of exile, disappointment, trepidation, punishment. It was like day and night. And, within the context of that broad, simple, westward movement, the endless, frenetic stitching back and forth among Frankfurt, Berlin, Paris, Vienna, Amsterdam to wherever he had temporarily pitched his tents; the long, journalistic visits to the south of France in 1925, to the Soviet Union in 1926, Albania and the Balkans in 1927, and Italy and Poland in 1928; the many tours the length and breadth of the German regions throughout the 1920s, for what became a sort of dreaded and dispiriting enemy terrain to which his newspaper bosses were quite deliberately dispatching their acutest, most high-strung war correspondent (the atmosphere in one particular town, Roth noted, was like that “five minutes before a pogrom”); the number of places (eleven, by my count) where he stopped to compose his masterpiece, The Radetzky March , between 1930 and 1932, on the face of it, his most comfortable circumstances ever, with a monthly retainer, less journalism, and Friedl cared for; and then the places of exile, where one has to picture him practically as a mendicant, borrowing or scrounging train fare, leaving Paris for Amsterdam to haggle over a new — and newly ruinous — publishing contract, or for Marseille because there was the prospect of free accommodation, albeit of a sort detested by this self-described “hotel patriot,” or Ostend, so that he might have daily access to his, alas, always pedagogically minded patron, Stefan Zweig. This swarming movement is one of the points of these letters.

Читать дальше