Joseph J. Torres - Life in the Open Ocean

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Joseph J. Torres - Life in the Open Ocean» — ознакомительный отрывок электронной книги совершенно бесплатно, а после прочтения отрывка купить полную версию. В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: unrecognised, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Life in the Open Ocean

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Life in the Open Ocean: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Life in the Open Ocean»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Life in the Open Ocean: The Biology of Pelagic Species

Life in the Open Ocean: The Biology of Pelagic Species

Life in the Open Ocean — читать онлайн ознакомительный отрывок

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Life in the Open Ocean», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

Pressure

The easiest physical characteristic of the ocean to understand is pressure. Pressure increases by 1 atmosphere (atm) (the barometric pressure at sea level) or 14.7 pounds per square inch (psi) with each increase of 10 m in depth. The metric unit of pressure is the pascal (Pa). One atmosphere is equivalent to 101.3 kPa. Pressure in the deepest point in the ocean, the Challenger Deep (depth: 10 916 m), is 16 046 psi or 1.11 × 10 5kPa. In contrast, pressure at the average depth of the ocean is 5586 psi or 3.85 × 10 4kPa. Pressure can be important in shaping the characteristics of species living in the deep sea and will be discussed in the next chapter.

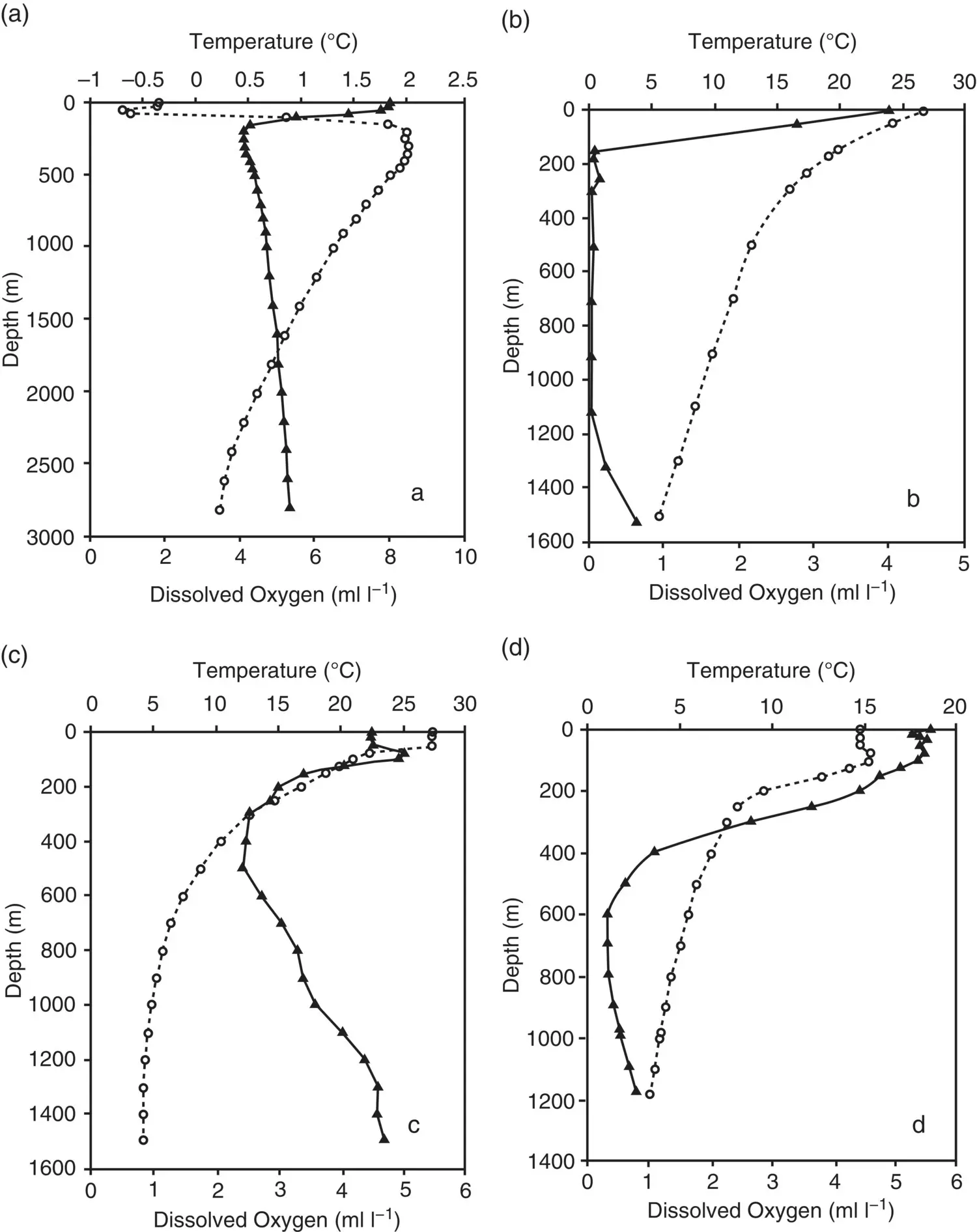

Figure 1.17 Oxygen and temperature profiles from four oceanic regions. (a) Antarctic (Southern Ocean); (b) Arabian Sea; (c) Gulf of Mexico; (d) California Current.

Source: Torres et al. (2012), figure 1 (p. 1909). Reproduced with the permission of The Company of Biologists.

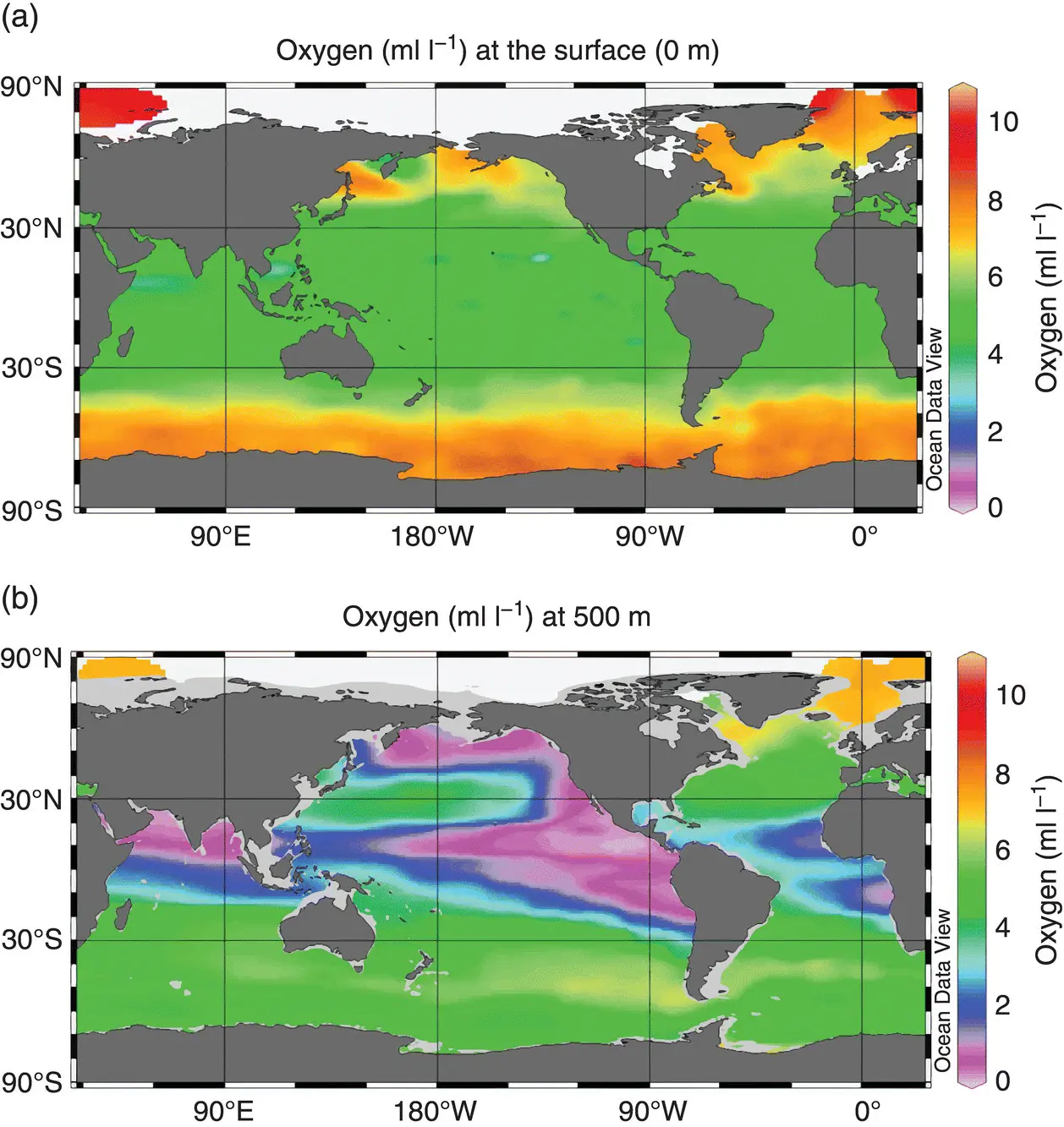

Figure 1.18 Typical oceanic oxygen concentrations. (a) Surface; (b) 500 m.

Sound

The ocean is sometimes characterized as a noisy place, though it may seem silent to scuba divers in the open ocean because most of the sounds are not discernible to human ears. Sound levels do vary considerably in the sea in the horizontal and vertical planes, and only a part is generated by the activities of humans. Detection of sound and other vibrations is a sensory modality shared by virtually all oceanic species. Some pelagic species, bottlenose dolphins, for example, use echolocation to locate prey, just as a bat does.

Sound levels do not vary predictably in the ocean except in a general sense. Increasing distance from the crashing waves of a rocky shore will decrease the levels of ambient sound, as will increasing depth and distance from the wind‐induced turbulence of surface waters. However, the properties of sound do vary predictably, and a presentation of some basic concepts now will help with later discussions of hearing and mechanoreception in open‐ocean fauna. The physics of sound is quite complex; only the most rudimentary aspects will be covered in this book.

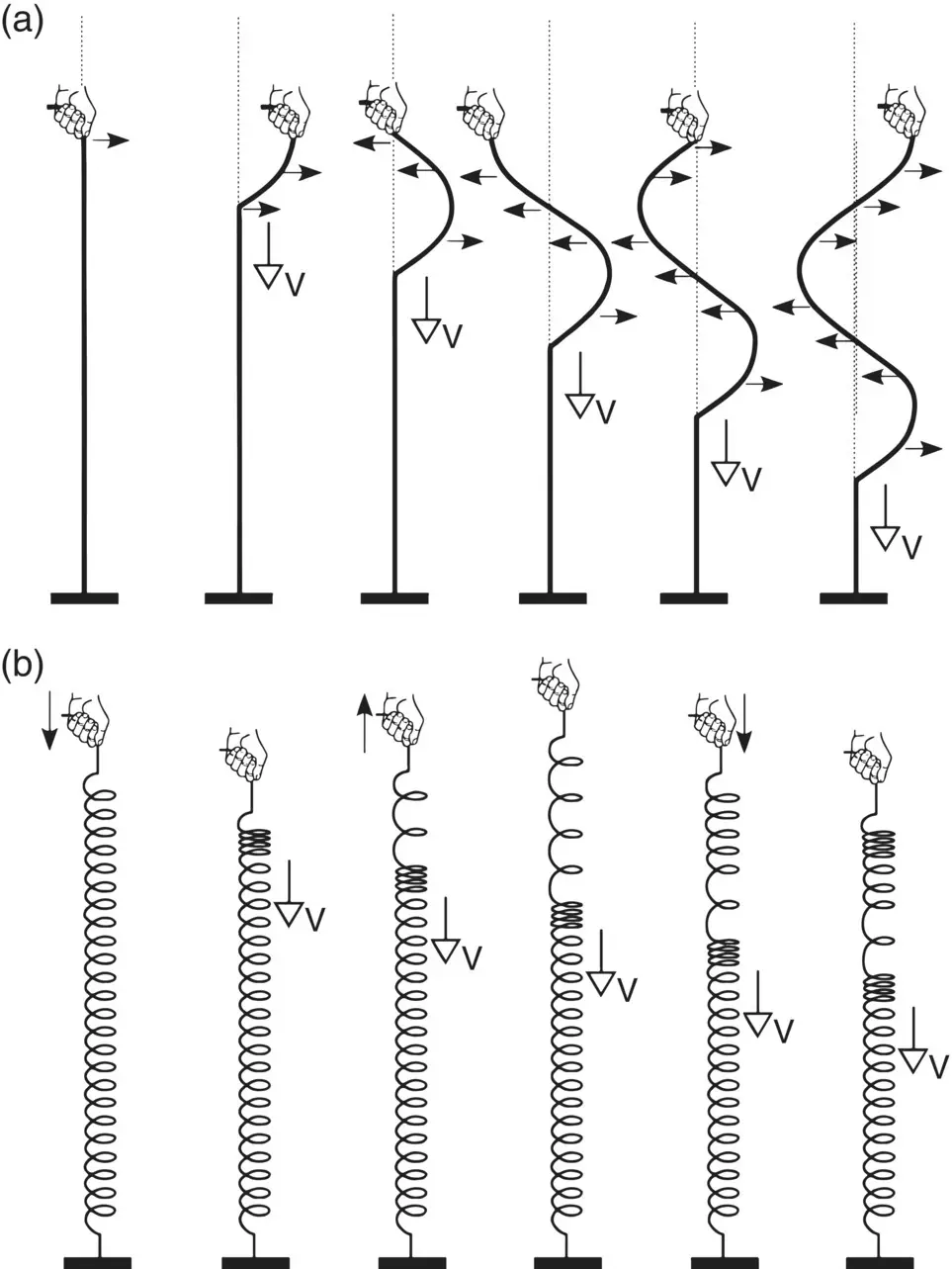

“Sound is a longitudinal mechanical wave that propagates in a compressible medium” (Rogers and Cox 1988). A mechanical wave results from the displacement of an elastic medium from its original position, causing it to oscillate about an equilibrium position ( Figure 1.19a; Halliday and Resnick 1970). The trick here is to recognize that the disturbance, or mechanical wave, moves through the medium with no resulting movement in the medium itself. A good visualization of the passage of a mechanical wave is to think of a cork bobbing while a surface wave passes underneath it. The cork moves up and down as the wave passes by, transferring some energy to it, but the cork does not follow in the wave’s path.

A longitudinal wave is propagated in a back and forth motion along the direction of propagation ( Figure 1.19a). This is in contrast to a transverse wave (such as an electromagnetic wave – see the treatment of light as follows), which yields a displacement at right angles to the axis of propagation. Visualize the propagation of sound through a medium by imagining the movement of a rapidly oscillating piston in a tube. As the piston moves back and forth, it creates regions of higher and lower pressure, areas of compression and rarefaction ( Figure 1.19b). Tiny volumes of water (water particles) oscillate in place as the areas of compression, or wave fronts, of the sound wave propagate past them. The hair‐like sensory elements of open‐ocean fauna are designed to detect the water motion, or vibration of sound, as it moves past them.

Figure 1.19 Mechanical wave propagation. (a) Transverse wave. Particles displaced perpendicular to the direction the wave travels; (b) Longitudinal wave. Particles displaced parallel to the direction the wave travels.

Source: Halliday and Resnick (1970), figure 16.1 (p. 301). Reproduced with the permission of John Wiley & Sons.

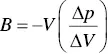

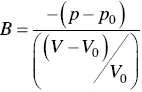

The speed of sound in a medium is a function of the medium’s compressibility: the stiffer the medium, the faster sound will propagate through it. That is why the speed of sound in water is very much faster (4.3 times faster) than it is in air. However, to know if the speed of sound varies with depth in the ocean, we need to know a little more than that. We already know that the density of water does not increase much with increasing pressure. The ratio of the change in pressure on a volume of water (Δ p ) to the resulting change in volume of that water (−Δ V / V ) is known as its bulk modulus of elasticity (“ B ”, Halliday and Resnick 1970, Denny 1993). B is positive because an increase in pressure results in a decrease in volume (or increase in density).

(1.9)

where Δ p is the change in pressure, Δ V is the change in volume, p is the ambient pressure, and V is the volume at the original pressure. Put in a more empirical way, the same equation can be expressed as (Denny 1993):

(1.10)

where p is the ambient pressure, p 0is the pressure at 1 atm, V is the volume at pressure p , and V 0is the volume at 1 atm. The bulk modulus of water is about 2 × 10 9Pa depending on the temperature, which is a very considerable pressure. As mentioned earlier, the Challenger Deep at about 11 km of depth would yield a pressure of about 10 9Pa, not nearly enough to double the density of water.

The speed of sound through water is equal to the square root of the ratio of its bulk modulus to its density (Denny 1993).

(1.11)

where c is the speed of sound, ρ is the density, and B is the bulk modulus.

The declining temperature and increasing pressure with increasing depth in temperate and tropical regions act to change the speed of sound such that there is both a maximum and a minimum velocity in the top 1500 m ( Figure 1.20). At the bottom of the mixed layer, the pressure has increased very slightly, increasing the B also very slightly, but the density has remained the same. The result is a maximum sound velocity at the bottom of the mixed layer. The minimum speed results from the influence of declining temperatures over the permanent thermocline. The increase in density with depth in the denominator is not enough to offset the decline in bulk modulus with depth resulting from the declining temperatures, producing a minimum speed near the bottom of the permanent thermocline. Once the bottom of the permanent thermocline is reached, the pressure continues to increase, but the temperature changes little. Pressure then becomes the main factor governing the speed of sound ( Eqs. 1.10and 1.11), which continues to increase with depth. Refraction of sound at the depths of maximum and minimum velocity has importance in submarine warfare, where echoes from pulses of high‐energy sound (SONAR) are used to locate enemy submarines.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Life in the Open Ocean»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Life in the Open Ocean» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Life in the Open Ocean» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.