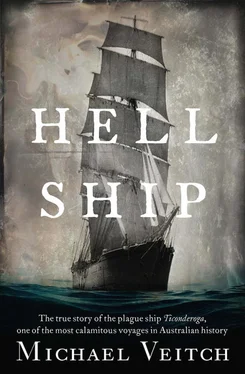

Captain Boyle faced a dilemma. The Ticonderoga was living up to her promise as a fast and well-built vessel, and for a while was even keeping pace with the Marco Polo ’s record-breaking run to Melbourne of just 68 days. What, however, would be the cost in taking full advantage of these southerly gales? As more of his passengers and crew became sick, Dr Sanger reported that the terrible tossing of the ship in the rough weather was making the situation far worse, not only for the patients themselves but also for his and Dr Veitch’s ability to care for them.

The two men consulted at length about striking a balance between delivering their increasingly sickening passengers to Melbourne as soon as possible and not causing even more deaths in the process. Because now death was everywhere.

The married quarters—first on the lower deck, then the upper—were the hardest hit. Freezing families huddling together became breeding grounds for colonies of lice, which moved from one warm body to another. Always the same pattern emerged, presenting particularly quickly with the children and infants: the pink rash that grew to blister almost the entire body, the terrible fever, the skin of loved ones almost unbearable to touch. With adults, a ranting delirium set in; with children, it was a coma then death.

In these terrible days of October, the Ticonderoga ’s exhausted doctors were given barely a moment’s rest. As Christopher McRae recalled in a letter to The Argus in January 1917, ‘I remember the Captain accompanying the Doctor, going through and seeing that things were in proper order, that is, as far as it was possible, under the circumstances.’ Cries for help rang throughout the ship, and Drs Sanger and Veitch answered all those they could, fighting the pitching of the vessel to make their way across the increasingly chaotic mess of the decks to another bunk, and another red and heaving patient staring with fixed, glassy eyes. Veitch carried the heavy medical chest, offered a sip of brandy or sweet wine to the deathly white lips of the patient, regardless of their age, while Sanger, in the half light and cloying atmosphere, set up his bottles and made up a tincture. Wet cloths were applied to cool the burning brow. Sometimes it seemed to work, with the patient’s overheated brain gaining some respite, even occasionally recovering. More often than not, though, it was all for nothing.

The Campbell family, listed as Presbyterians from Argyllshire, were all but wiped out in a month. John, 44, and his tiny daughter, two-year-old Jane, died within hours of each other on 5 October. Allan, an otherwise healthy lad of eighteen, would join his father and sister on 18 October, to be followed by another sibling, Peggy, a short time later.

The ship’s hospitals—both male and female—were soon overflowing into the narrow and inadequate corridors. Sanger and Veitch had to virtually force their way through to reach bodies prone on the floor, or in makeshift cots, to administer at least some semblance of treatment. Both knew that their medical supplies were running dangerously low. Soon, with the postponement of funerals due to the rough weather, the hospitals became morgues, filled to capacity, making them resemble an overflowing charnel house. The sick were ordered to stay in their bunks and wait to be treated there, only to be moved to the hospital once a patient had died. Those occupying neighbouring bunks watched with horror as the terrible symptoms took the patient closer and closer to death, and wondered when their turn would come. [1] Letter from Christopher McRae to Mr Kendall, 1917

The pace of sea burials increased—now a far cry from the early dignified ceremonies presided over by the captain. They were now hasty affairs, conducted quickly between breaks in the weather, watched over by almost no one. Now it was one of the ship’s mates or even the redoubtable schoolmaster and impromptu minister of religion, Charles McKay, who was called upon to repeat the same few desultory words as yet another deadweight was tipped over the side, making a brief white splash into the slate-grey water as shocked and sobbing family looked on. The Ticonderoga ’s sail-makers, in whose canvas the bodies were sewn, had permanent work as the ship’s undertakers. There was a pervasive and morbid fear of who would be next, with no one daring to contemplate how much worse the epidemic could become. Then another squall would roll in, and everyone but the crew would be ordered below.

A macabre backlog started to evolve, with more and more victims needing to be disposed of simultaneously. Years later, in January 1909, in one of just a handful of first-hand accounts given in a letter to The Argus , James Dundas recalled travelling as a nine-year-old with his family of five from Aberdeen:

I saw, more than once, ten buried in one day. They were tied up in bedding and mattresses, all together, and thrown overboard, to float away, as there was nothing to weight the corpses with. If we had not got to land when we did, I do not think there would have been many left to tell the tale.

On 11 October, Dundas watched his two-year-old sister, Elizabeth, burn up in a fever and expire in a matter of hours. The sounds of the sobbing of his father Lewis, 34, and mother Isabella, 36, would haunt him the rest of his life.

A graph prepared in 2002 by a diligent amateur historian of the Ticonderoga ’s grisly journey plots the frequency of deaths over the course of her 90-day voyage. [2] Victorian Public Records Office, 2002, ‘Register of Births and Deaths of Emigrants at Sea 1847-53’, CO 386/170, Folios 85–90

Over the first few weeks of August and into September, the curve is mainly flat, with one or two rises and falls representing the ship’s handful of early fatalities. Then, as the 60th day of the voyage is reached, around the first day of October, the graph begins to rise. The curve is gentle at first, but it increases dramatically as the month proceeds, attesting that almost half of the Ticonderoga ’s approximately 104 deaths at sea occurred within the last two weeks of October.

One of the reasons for this was discovered by Sanger and Veitch early one evening when called to attend a sick Englishwoman in her bunk on the lower deck. Even in daytime, the poor light made vision difficult, but at night the few swinging whale oil lamps offered only the most pitiful spluttering gloom. This perhaps afforded the patient at least a modicum of comfort, as one of the symptoms of the disease is an agonising sensitivity to light.

Having attended the woman in this cave-like atmosphere, the two doctors made their way back to the gangway when they noticed a family huddled over their child. Dr Sanger interjected to inspect the mite, finding her to be already in the advanced stages of a raging fever. Astonished, he looked at the parents and inquired angrily why he hadn’t been informed of her condition. They shrugged, but seemed reluctant to engage him any further. Dr Veitch was astonished that a parent would fail to report a sick child under such circumstances, and sought to remonstrate, but Sanger restrained him. Leading him away, he assured his less experienced assistant that it was an all too depressingly common occurrence.

The Scots Highlanders, warily looked upon as dangerous outsiders even by their fellow countrymen in the south, were unused to outside interference or assistance of any sort—particularly medical attention from those not connected with their small community. For centuries, the traditional home remedies of their village and extended family had, for better or worse, sufficed. Added to this were a language barrier and a deep suspicion of outsiders, including those from the southern parts of Scotland, and particularly the English, as 800 or so years of conflict between the two kingdoms, followed by the recent Clearances, attested.

Читать дальше