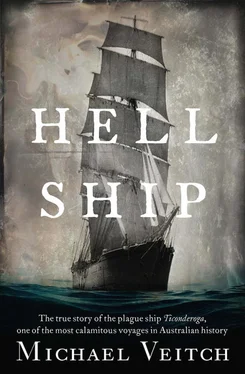

We had a most fearful night, it has blown a perfect hurricane… Nearly every minute a large wave broke on our deck and the wind sounded fearfully. All we could hear besides was the Captain and mate shouting to the men all night. [6] Charlwood, 1981, p. 287

And the next day:

Another very cold day, the wind cuts down our hatchway and nearly blows the hair off our heads and we are obliged to sit with a thick shawl on and even then we cannot keep a spark of warmth in us. [7] Charlwood, 1981, p. 287

The following day’s entry was even more dramatic:

It has been a most terrific night, such a one as makes young people old in one night for it was a regular night of horrors, the wind blew a perfect hurricane and every now and then the ship seemed perfectly under water and it poured down the hatchway in a perfect deluge. It is at such times as that we feel the comfort of having a top berth for the people in the bottom ones get washed out of their beds. The screams of the people as each wave comes down the hatchway was enough to make the stoutest heart to tremble. [8] Charlwood, 1981, p. 287

According to Mary Kruithof, throughout the last month of the voyage, the Ticonderoga was ‘overtaken by storm after storm… each one lasting for days at a time’. [9] Kruithof, 2002, p. 54

Memories of warm equatorial evenings spent in calm and cordial conversation on the upper deck were now so distant that many of the passengers questioned whether they had taken place at all. Then, the heat had sometimes seemed unbearable, but what would they now give to have just one of those evenings back again?

Shivering with cold as well as fright in their dank beds, the Ticonderoga ’s passengers endured hour after hour, day after day huddled in the confines of their berths, feeling the ship tossed and pummelled by the screeching wind that drove the seas before it into a monstrous frenzy. The awful seasickness that they thought they had left behind now returned. It seemed the sea was determined to invade the confines of the ship, and even tightly closed scuttles shrieked and whistled as water pushed its way through every inadequate gap and seal.

During the big storms, the galley system all but broke down. Coppers were upset and fires were extinguished as soon as they could be lit by the exasperated cooks. Besides, moving about the ship—for anyone—under such conditions was perilous. Those who did so frequently came to grief on ladders or simply slipped on the icy deck. Skulls were thrown against bulkheads, elbows and ankles cracked as the lurching ship threw everything inside against its wooden interior. Those who risked getting up from their cots to answer the call of nature had to grip hard with both hands to avoid being hurled as a wave struck. People tripped and skidded on the swirling mass of water and all the possessions tumbling around on the floors. Some intrepid souls who could no longer bear the confines of the lower decks occasionally ventured out onto the top open deck and described it as akin to trying to walk on a pitched roof.

Even the single men, who had assumed their recent roles as sailors with such gusto—even to the point of starting to affect the talk and manners of the real old salts—were stunned into silent terror. From their quarters in the bow of the ship, the dreadful lurching of the vessel as it plunged down the troughs of 15- and 20-metre waves was at its most extreme. Like a train plummeting over a precipice, their hands—white knuckled—would grip the wooden rails of their cots as the ship lurched forward, throwing everything not bolted down into a cacophonous clatter of pans and cutlery. Foot-lockers burst open, spilling their contents. Then came the great crash as the ship’s bow hit the bottom of the trough, burying the upper deck under metres of sea water before the ship miraculously recovered once again. As terrifying an ordeal as this was, the men knew that above them, somewhere, the real seamen were at work, on the deck and in the rigging, climbing the mainyards and somehow managing to stay upright to grapple with the ship in the face of the storm. For them, the real terror came from the mighty swells that rose up from the Ticonderoga ’s stern, stealing her wind before breaking over her in a deluge and turning her bursting sails into sagging sheets of sodden canvas.

Captain Boyle was up there too, somewhere in his sou’wester high up on the forecastle. Between the bouts of wind, they could occasionally hear him barking out his orders, encouraging his helmsman, driving his army of men trained to fight this impossible struggle against the raging elements—one he could not afford to lose. The Ticonderoga was strong, and her raked bow could slice apart the fiercest of waves, but should she allow the wind to turn her side-on, to slip into the lee of one of those monstrous swells, Boyle knew that the sea could overcome her in seconds, her yardarms turned turtle into the water, her leaden sails dragging her over as another wave pounded across her decks. Then, in moments, she would be pulled to the bottom like a stone. It happened all the time, he knew, to finer ships manned by finer crews than his.

While no list remains of the Ticonderoga ’s crew, they were believed to have numbered 48 in total, and were all experienced sailors. But although the runs across the Atlantic could be fierce at times, none had seen seas comparable to the ferocity of these oceans swirling around the bottom of the globe. Boyle had done his best to make them aware back in Liverpool that conditions further south would be rough, but no one had envisaged this.

George Pollock Russell, a Scotsman whose journal of his 1854 voyage has survived (due to the diligence of his granddaughter, Eunice), was likewise shocked by the severity of the weather:

It is quite out of the question to walk on deck it is leaning at about an angle of 45 degrees… at half past seven in the evening a wave struck the ship with such force, we thought for certain the ship was going down. The storm is now raging fearfully; some are going to bed, others are stopping up… the sea is washing over the decks and into our beds… our table is broken in a heap in the middle of the floor… I turned into bed about 1 O’clock but did not sleep. [10] Journal of George Pollock Russell, voyage of 1854

To compound the passengers’ misery, in such seas the innovative fresh air canvas ventilation system scooping fresh air from up top and distributing it below was disengaged, lest it become a conduit for seawater—which was everywhere in any case for those people cocooned in the lower decks. Hatches that were easily battened down and secured in calm seas burst and tore away, allowing cascading torrents to gush into the bowels of the ship. Waves crashing onto the deck forced water down through every deck board, gap and opening. Diarist William Johnstone, sailing the Great Circle route on the Arab a few years later, recalled that:

The between decks where the Emigrants were all stowed away (sometimes a man and his wife and two children in the one bed) were in a most horrible condition. The seas washed down the hatchways and the floor was a complete pont, many of the beds drenched through and through. In addition to these delights, with four or five exceptions, they were all violently seasick—some of the women fainting, and two going into convulsions—all call out for Brandy, which they had been told by the Emigrant Agent had been put on board for their use—but which they now found ‘non est inventus’. The squall had come on so suddenly that their boxes were all adrift, flying about from one side to the other, with nearly 50 whining sick squalling children to complete their misery. [11] Charlwood, 1981, p. 126

Читать дальше