These mutations disrupt a series of genes that, in homage to William Bateson, have come to be known as the homeotic genes. There are eight of them, and they have names like Ultrabithorax, Antennapedia or, less euphemistically, ‘deformed’, that recall the strange flies produced when they are disrupted by mutation. They are the variables in a calculation that makes each segment distinct from any other.

The segmental calculator is a thing of beauty. It has the economical boolean logic of a computer programme. Each of the proteins encoded by the homeotic genes is present in certain segments. Some are present in the head, others in the thorax, others in the abdomen. The identity of a segment – the appendages it grows – depends on the precise combination of homeotic proteins present in its cells. The calculation for the third thoracic segment, which normally bears a haltere, looks something like this:

If Ultrabithorax is present

And all other posterior homeotic proteins are absent

Then third thoracic segment: HALTERE.

Which simply implies that Ultrabithorax is necessary if the third thoracic segment is to grow a haltere, that is, to be a third thoracic segment. Should the gene be crippled by a mutation, the protein that it encodes, if present at all, will be unable to do its work. The segment’s unique identity is lost; it becomes a second thoracic segment instead and carries wings.

When, in the 1980s, the homeotic genes were cloned and sequenced they proved to encode molecular switches: proteins that turn genes on and off. Molecular switches work by controlling the production of messenger RNA. Most genes contain information to make proteins. But this information requires a means of transmission. That is the job of messenger RNA, a molecule much like DNA except that it is neither double nor a helix, but only a long string of nucleotides. Messenger RNA is a copy of DNA, produced by a device that travels down gene sequences rather as a locomotive travels down a track. Molecular switches – or, to give them their proper name, ‘transcription factors’ – control this. Binding to ‘regulatory elements’, small, exact DNA sequences that surround every gene, transcription factors reach over to the molecular engine that makes messenger RNA and attempt to influence its workings. Some transcription factors seek to speed the engine up; others to shut it down. Attached to their regulatory elements, transcription factors face each other over the double helix and dispute for control. Like all negotiations, the outcome depends on the balance of power: the diversity of the opposing forces, or just their numbers.

The sequences of the eight fly homeotic genes are quite different. Yet each has a region, a sequence of only 180 base-pairs, that encodes, with small variations, the following string of amino acids:

RRRGRQTYTRYQTLELEKEFHTNHYLTRRRRIEMAHALCLTERQIKIWFQNRRMKLKKEI.

This is the homeobox. In the sub-microscopic bulges and folds of a homeotic protein’s three-dimensional topology it is the homeobox sequence, nestling within the grooves of the double helix of the DNA, that brings the homeotic proteins to their targets, the hundreds, perhaps thousands, of genes under their control. Subtle differences in the homeobox of each protein allows it to control particular suites of genes.

The discovery of the homeobox in 1984, distinctive as a Hapsburg’s lip, suggested that the homeotic genes were all related to each other, that they were a family. Other animals, it quickly became apparent, had homeobox genes as well. They were found in worms and in snails, in starfish, fish, mice, and they were found in us. Perhaps they were present in the very first animals that crawled out of the Pre-Cambrian ooze a billion years ago. Most excitingly, if homeobox genes formed the circuits of the fly’s calculator of parts, might they not do so for all creatures, even for humans? Molecular biologists are not a breed much given to hyperbole, but when they found the homeobox, they spoke of Holy Grails and of Rosetta Stones.

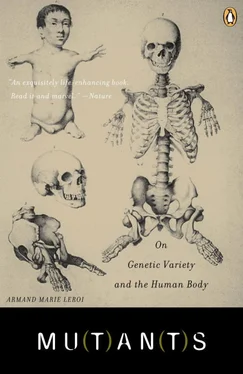

They were right to do so. Another of Vrolik’s specimens, this time a skeleton, shows why. At first glance it seems a rather dull sort of skeleton. It isn’t bent with rickets or bowed with achondroplasia; there is nothing unusual about it (though its skull, limbs and pelvis have evidently long gone astray). It is only an undulating vertebral column with brownish ribs on a rusted metal stand – an altogether abject thing. It is not even on display in the public galleries, but lives in a basement where it is shelved with dozens of other skeletons accumulated over a century but now largely surplus to requirements. And yet this skeleton enjoys a quiet renown. Each spring it sees the light of day as it is displayed to a new batch of the Rijkuniversiteit’s medical students who are invited to identify its anomaly. This is surprisingly hard to spot, though obvious once pointed out – it is an extra pair of ribs.

Extra ribs have always caused trouble. In his Pseudodoxia epidemica Sir Thomas Browne relates how once, when the anatomist Renaldus Columbus dissected a woman at Pisa who happened to have thirteen ribs on one side, ‘there arose a party that cried him down, and even unto oaths affirmed, this was the rib wherein a woman exceeded’. ‘Were this true,’ Browne continues, ‘this would oracularly silence that dispute out of which side Eve was framed.’ The influence of Genesis II: 21–22 on popular anatomy has been a baleful one. I recently asked a class of thirty biology undergraduates (among them Britain’s best and brightest) whether men and women had the same number of ribs: about half a dozen of them thought not. ‘But,’ as Sir Thomas says with customary vigour, ‘this will not consist with reason or inspection. For if we survey the Sceleton of both sexes, and therein the compage of bones, we shall readily discover that men and women have four and twenty ribs, that is, twelve on each side.’ Just so. And yet extra ribs are surprisingly common: one in every ten or so adults has them (but they are no more or less frequent in women than men).

Most of us have thirty-three vertebrae. Starting at the head, there are seven neck vertebrae, then twelve rib-bearing vertebrae, then five vertebrae in the lower back, and another nine fused together to make the sacrum and coccyx or tail bones. In most people with extra ribs, this pattern is disrupted. A vertebra that normally does not bear ribs has become transformed into one that does. Sometimes this means the loss of a neck vertebra, sometimes the loss of one in the lower back; either way, homeotic transformations are much like the segment transformations that geneticists seek in their mutant flies.

It is no surprise, then, that the identity of each vertebra is controlled by homeotic genes much like those that keep a fly’s segments in order. Of course, matters are rather more complicated for us. Flies have only eight homeotic genes while mammals have thirty-nine, so many that the evocative Latinate names have been dropped: no Ultrabithorax or proboscipedia for us, but only the prefix Hox followed by unmemorable letters and digits: Hoxa3, Hoxd13 and so on. In mammals, as in flies, homeotic genes begin their work early in the life of the embryo. Vertebrae develop from blocks of mesoderm called somites that form on either side of the nerve cord like rows of little bricks. Each homeotic protein is present in just some of the somites. All thirty-nine are present in the tail somites, but then they fall away, in ones and twos, so that finally only a handful remain in the somites closest to the head. The vertebral calculator is not very economical. For the seventh neck vertebra it looks something like this:

If Hoxa4 is present

And Hoxa5 is present

And Hoxb5 is present

Читать дальше