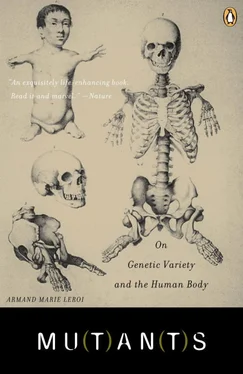

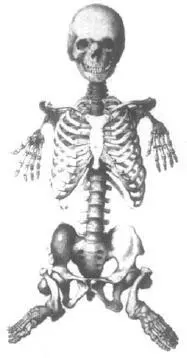

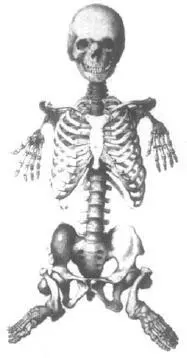

PHOCOMELIA. SKELETON OF MARC CAZOTTE, A.K.A. PEPIN (1757–1801). FROM WILLEM VROLIK 1844–49 TABULAE AD ILLUSTRANDAM EMBRYOGENESIN HOMINIS ET MAMMALIUM TAM NATURALEM QUAM ABNORMEM.

The fallacy of the mark of Cain flourished in Britain – football coaches aside – as recently as the seventeenth century. In 1685, in the remote and bleak Galloway village of Wigtown, two religious dissenters, Margaret McLaughlin and Margaret Wilson, were tried and convicted for crimes against the state. The infamy of their case comes from the cruelty of the method by which they were condemned to die. Both women were tied to stakes in the mouth of the River Bladnoch and left to the rising tide. Various accounts, none immediately contemporary, tell how they died. McLaughlin, an elderly widow, was the first to go; Wilson, who was eighteen years old, survived a little longer. A sheriff’s officer, thinking that the widow’s death-throes might concentrate the younger woman’s mind, urged her to recant: ‘Will you not say: God bless King Charlie and get this rope from off your neck?’

He underestimated the girl. Some accounts give her reply as a long and pious speech; others say she sang the 25th Psalm and recited Chapter 8 of Romans; all agree that her last words were pure defiance: ‘God bless King Charlie, if He will.’ The officer’s response was to give vent to his talent for vernacular wit. ‘Clep down among the partens and be drowned!’ he cried. And then he grasped his halberd and drowned her.

The executioner’s words are interesting. In the old Scottish dialect to ‘clep’ is to call; ‘partens’ are crabs. Thus: ‘Call down among the crabs and be drowned.’ In another version of the story, the officer was asked (by someone who had evidently missed the fun) how the women had behaved as the waters rose around them. ‘Oo,’ he replied in high humour, ‘they just clepped roun’ the stobs like partens, and prayed.’ Either way, it is here that the story slides from martyrology into myth. For it seems that shortly after the officer – a man named Bell – had done his cruel work, his wife gave birth to a child who bore the ineradicable mark of its father’s guilt: instead of fingers, its hands bore claws like those of a crab. ‘The bairn is clepped!’ cried the midwife. The mark of Bell’s judicial crime would be visited on his descendants, many of whom would bear the deformity; they would be known as the ‘Cleppie Bells’.

The spot at which the women are supposed to have died was marked by a stone monument in the form of a stake; today it stands in a reed-bed far from the water’s edge, the Bladnoch having shifted course in the intervening three centuries. Another, far more imposing, monument to the martyrs stands on a hill above the town, and their graves, with carefully kept headstones, may be found in the local churchyard. Here, as elsewhere, the Scots nurse the wounds of history with relish.

There are are other modern echoes of the event as well. As recently as 1900, a family bearing the names Bell or Agnew, and possessing hands moulded from birth into a claw-like deformity, lived in the south-east of Scotland and were said to be descendants of the Cleppie Bells. We know nothing more about them; they may be there yet. We do know that in 1908 a large, unnamed family, living in London but of Scottish descent, were the subject of one of the first genetic studies of a human disorder of bodily form. Their deformity, known at the time as ‘lobster-claw’ syndrome, is certainly the same malformation that the Cleppie Bells had, though these days clinical geneticists eschew talk of ‘lobster claws’ and speak of ‘split-hand-split-foot syndrome’ or ‘ectrodactyly’, a term rendered palatable only by the obscurity of Greek, in which it reads as ‘monstrous fingers’. This second Scots family may have been related to the Cleppie Bells, but it is quite possible that they were not and that the deformity arose independently in the two families. At one end of this story there is the historical trial and death of Margarets Wilson and McLaughlin, at the other there are the Cleppie Bells and a clinical literature. The mythical element, of course, lies in the causal connection between the two. Nothing that officer Bell ever did could have caused his descendants to be born with only two digits on each hand, widely spaced apart. If the Bells were clepped, it was because some of them carried a dominant mutation that affected the growth of their limb-buds while they were still in the womb: it certainly had nothing to do with the partens.

SPLIT-HAND-SPLIT-FOOT, OR ECTRODACYTLY, OR LOBSTER-CLAW SYNDROME. GIRL WITH RADIOGRAPH OF MOTHER’S FOOT, ENGLAND. FROM KARL PEARSON 1908 ‘ON THE INHERITANCE OF THE DEFORMITY KNOWN AS SPLIT-FOOT OR LOBSTER CLAW’.

The fragments of myth, folklore and tradition that remain to us from a pre-scientific age are like the marks left in sand by retreating waves: void of power and meaning, yet still possessed of some order. Muddied by time and confused causality, they still bear the imprint of the regularities of the natural world. It is surely significant that in such lore – no matter what its origin – few parts of the human body are as vulnerable to deformity as the limbs. Greek mythology has only one deformed Olympian, crook-foot Hephaestus who, abandoned by Hera (his mother), betrayed by Aphrodite (his wife), and spurned by Athena (his obsession), nevertheless taught humanity the mysteries of working metal and so is the god of craftsmen and smiths. Depicted on black-and-red-ware he is usually given congenital bilateral talipes equinovarus, or two club-feet. Oedipus, perhaps the most famous deformed mortal, wore his swollen foot in his name.

New myths arise even now. In the mid-1960s a Rhodesian Native Affairs administrator claimed that he knew of a tribe of two-toed people in the darker reaches of the Zambezi river valley. In tones reminiscent of Pliny the Elder’s accounts of fabulous races in Aethiopia or the Indies they were, he said, variously called the Wadoma, Vadoma, Doma, Vanyai, Talunda or, most excitingly, the ‘Ostrich-Footed People’ – a primitive and reclusive group of hunter-gatherers who, by virtue of their odd feet, could run as swiftly as gazelles. Veracity was assured by a photograph of a Wadoma displaying his remarkable feet. In 1969 this same photograph appeared in the Thunderbolt , a newsletter published by the American National States Rights Party, illustrating an article which argued that since some Africans had ‘animal feet’ they were obviously a separate species (‘Negro is related to Apes – Not White People’). American academics, rightly outraged, denounced the photograph as a forgery. Wrongly so, for when geneticists investigated the matter, they found that the Wadoma certainly existed, although far from being a whole tribe of ‘ostrich-footed’ people, there was only a single family afflicted with an apparently novel variety of ectrodactyly. But it is impossible to keep a good myth down. In the mid-1980s two South African journalists claimed they had stumbled across a whole tribe of two-toed people in the darker reaches of the Zambezi. Now, websites assert that the Wadoma worship a large metal sphere buried in the jungle and are, in fact, extraterrestrials.

Limbs have an extraordinary knack for going wrong. There are more named congenital disorders that affect our limbs than almost any other part of our bodies. Is it that limbs are particularly delicate, and so prone to register every insult that heredity or the environment imprints upon them? Or is it that they are especially complex? Delicate and complex they are, to be sure, but the more likely reason for the exuberant abundance of their imperfections is simply that they are not needed, at least not for life itself. Children may grow in the womb and be born with extra fingers, a missing tibia, or missing a limb entirely, and yet be otherwise quite healthy. They survive, and we see the damage.

Читать дальше