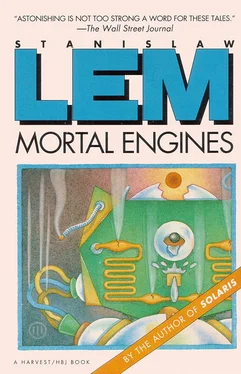

Stanislaw Lem - Mortal Engines

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Stanislaw Lem - Mortal Engines» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Город: London, Год выпуска: 1992, ISBN: 1992, Издательство: André Deutsch, Жанр: Фантастика и фэнтези, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Mortal Engines

- Автор:

- Издательство:André Deutsch

- Жанр:

- Год:1992

- Город:London

- ISBN:0-233-98819-X

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Mortal Engines: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Mortal Engines»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

“Astonishing is not too strong a word for these tales”

(Wall Street Journal).

Mortal Engines — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Mortal Engines», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

I was about to move on when he rose and, brushing from his sleeve the hanging fringe of the brocade, as if to indicate the comedy was over, came towards me. Two steps and he stopped, now overtaken by the awareness of how impertinent was that unequivocal action, how very scatterbrained it would appear, to go walking after an unknown beauty like some gaping idiot following a band, so he stood, and then I closed one hand and with the other let slip from my wrist the little loop of my fan. For it to fall. So he immediately…

We looked at each other, now up close, over the mother-of-pearl handle of the fan. A glorious and dreadful moment, a mortal stab of cold caught me in the throat, transfixing speech, therefore feeling that I would not bring forth my voice, only a croak, I nodded to him—and that gesture came out almost exactly as the one before, when I did not complete my bow to the King who wasn’t looking.

He did not return the nod, being much too startled and amazed by what was taking place within him, for he had not expected this of himself. I know, because he told me later, but had he not, even so I would have known.

He wanted to say something, wanted not to cut the figure of the idiot he most certainly was at that moment, and I knew this.

“Madam,” he said, clearing his throat like a hog. “Your fan…”

By now I had him once more in hand. And myself.

“Sir,” I said, and my voice in timbre was a trifle husky, altered, but he could think it was my normal voice, indeed he had never heard it until now, “must I drop it again?”

And I smiled, oh, but not enticingly, seductively, not brightly. I smiled only because I felt that I was blushing. The blush did not belong to me, it spread on my cheeks, claimed my face, pinkened my ear lobes, which I could feel perfectly, yet I was not embarrassed, nor excited, nor did I marvel at this unfamiliar man, only one of many after all, lost among the courtiers—I’ll say more: I had nothing whatever to do with that blush, it came from the same source as the knowledge that had entered me at the threshold of the hall, at my first step upon the mirror floor—the blush seemed part of the court etiquette, of that which was required, like the fan, the crinoline, the topazes and coiffures. So, to render the blush insignificant, to counteract it, to stave off any false conclusions, I smiled—not to him, but at him, exploiting the boundary between mirth and scorn, and he then broke into a quiet laugh, a voiceless laugh, as if directed inward, it was similar to the laughter of a child that knows it is absolutely forbidden to laugh and for that very reason cannot control itself. Through this he grew instantly younger.

“If you would but give me a moment,” he said, suddenly serious, as if sobered by a new thought, “I might be able to find a reply worthy of your words, that is, something highly clever. But as a rule good ideas come to me only on the stairs.”

“Are you so poor then in invention?” I asked, exerting my will in the direction of my face and ears, for this persistent blush had begun to anger me, it constituted an invasion of my freedom, being part—I realized—of that same purpose with which the King had consigned me to my fate.

“Possibly I ought to add, ‘Is there no help for this?’ And you would answer no, not in the face of a beauty whose perfection seems to confirm the existence of the Absolute. Then two beats of the orchestra, and we both become dignified and with great finesse put the conversation back on a more ordinary courtly footing. However, as you appear to be somewhat ill-at-ease on that ground, perhaps it would be best if we do not engage in repartee…”

He truly feared me now, hearing these words—and was truly at a loss for what to say. Such solemnity filled his eyes, it was as if we were standing in a storm, between church and forest—or where there was, finally, nothing.

“Who are you?” he asked stiffly. No trace of triviality in him now, no pretense, he was only afraid of me. I was not afraid of him at all, not in the least, though in truth I should have been alarmed, for I could feel his face, with its porous skin, the unruly, bristling brows, the large curves of his ears, all linking up inside me with my hitherto hidden expectation, as though I had been carrying within myself his undeveloped negative and he had just now filled it in. Yet even if he were my sentence, I had no fear of him. Neither of myself nor of him, but I shuddered from the internal, motionless force of that connection—shuddered not as a person, but as a clock, when with its assembled hands it moves to strike the hour—though still silent. No one could observe that shudder.

“I shall tell you by and by,” I answered very calmly. I smiled, a light, faint smile, the kind one gives to cheer the sick and feeble, and opened up my fan.

“I would have a glass of wine. And you?”

He nodded, trying to pull onto himself the skin of this style, so foreign to him, poorly fitting, cumbersome, and from that place in the hall we walked along the parquet, which ran with pearly streams of wax that fell in drops from the chandelier, through the smoke of the candles, shoulder to shoulder, there where by a wall pearl-white servants were pouring drinks into goblets.

I did not tell him that night who I was, not wishing to lie to him and not knowing the truth myself. Truth cannot contradict itself, and I was a duenna, a countess and an orphan, all these genealogies revolved within me, each one could take on substance if I acknowledged it, I understood now that the truth would be determined by my choice and whim, that whichever I declared, the images unmentioned would be blown away, but I remained irresolute among these possibilities, for in them seemed to lurk some subterfuge of memory—could I have been just another unhinged amnesiac, who had escaped from the care of her duly worried relatives? While talking with him, I thought that if I were a madwoman, then everything would end well. From insanity, as from a dream, one could free one self—in both cases there was hope.

When in the late hours—and he never left my side—we passed by His Majesty for a moment, before he was pleased to retire to his chambers, I felt that the ruler did not even bother to look in our direction, and this was a terrible discovery. For he did not make sure of my behavior at the side of Arrhodes, that was apparently unnecessary, as though he knew beyond all doubt that he could trust me completely, the way one trusts—in full—dispatched assassins, who strive as long as they have breath, for their fate lies in the hands of the dispatcher. The King’s indifference ought to have, instead, wiped away my suspicions; if he did not look in my direction, then I meant nothing to him, nevertheless my insistent sense of persecution tipped the scales in favor of insanity. So it was as a madwoman of angelic beauty that I laughed, drinking to Arrhodes, whom the King despised as no other, though he had sworn to his dying mother that if harm befell that wise man it would be of his own choosing. I do not know if someone told me this while dancing or whether I learned it from myself, for the night was long and clamorous, the huge crowd constantly separated us, yet we kept finding each other by accident, almost as if everyone there were party to the same conspiracy—an obvious illusion, we could hardly have been surrounded by a host of mechanically dancing mannequins. I spoke with old men, with young women envious of my beauty, discerning innumerable shades of stupidity, both good-natured and malicious, I cut and pierced those useless dodderers and those pouting misses with such ease, that I grew sorry for them. I was cleverness itself, keen and full of witticisms, my eyes took on fire from the dazzling quickness of my words—in my mounting anxiety I would have gladly played a featherbrain to save Arrhodes, but this alone I could not manage. My versatility did not extend that far, alas. Was then my intelligence (and intelligence signified integrity) subject to some lie? I devoted myself to such reflections in the dance, entering the turns of the minuet, while Arrhodes, who didn’t dance, watched me from afar, black and slender against the purple brocade in crowned lions. The King left, and not long afterwards we parted, I did not allow him to say anything, to ask anything, he tried and paled, hearing me repeat, first with the lips, “No,” then only with the folded fan. I went out, not having the least idea of where I lived, whence I had arrived, whither I would turn my eyes, I only knew that these things did not rest with me, I made efforts, but they were futile—how shall I explain it? Everyone knows it is impossible to turn the eyeball around, such that the pupil can peer inside the skull.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Mortal Engines»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Mortal Engines» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Mortal Engines» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.