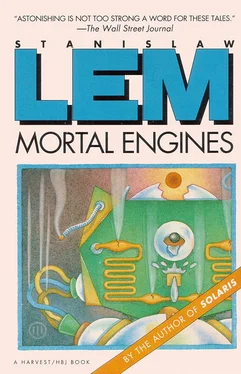

Stanislaw Lem - Mortal Engines

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Stanislaw Lem - Mortal Engines» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Город: London, Год выпуска: 1992, ISBN: 1992, Издательство: André Deutsch, Жанр: Фантастика и фэнтези, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Mortal Engines

- Автор:

- Издательство:André Deutsch

- Жанр:

- Год:1992

- Город:London

- ISBN:0-233-98819-X

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Mortal Engines: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Mortal Engines»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

“Astonishing is not too strong a word for these tales”

(Wall Street Journal).

Mortal Engines — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Mortal Engines», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

But there were two things I still did not know, though I realized, if obscurely still, that they were the most important. I did not understand why the King had ignored me as I passed, why he had refused to look me in the eye when he neither feared my loveliness nor desired it, indeed I felt that I was truly valuable to him, but in some inexplicable way, as if he had no use for me myself, as if I were to him someone outside this glittering hall, someone not made for dancing across the mirrorlike, waxed parquet arranged in many-colored inlays between the wrought-bronze coats of arms above the lintels; yet when I swept by, not a thought surfaced in him in which I could divine the royal will, and even when he had sent after me that glance, fleeting and casual, though sighted along an invisible barrel, I understood that it was not at me that he had leveled his pale eye, an eye which ought to have been kept behind dark glasses, for its look feigned nothing, unlike the well-bred face, and stuck in the milling elegance like dirty water left at the bottom of a washbowl. No, his eyes were something long ago discarded, something requiring concealment, not enduring the light of day.

But what could he want of me, what? I was not able to reflect on this however, for another thing claimed my attention. I knew everyone here, but no one knew me. Except possibly he, he alone: the King. At my fingertips I now had knowledge of myself as well, my feelings grew strange as I slowed my pace, three quarters of the hall already crossed, and in the midst of the multicolored crowd, faces gone numb, their side whiskers silvery with hoarfrost, and also faces blood-swollen and perspiring under clotted powder, in the midst of ribbons and medals and braided tassels there opened up a corridor, that I might walk like some queen down that path parted through humanity, escorted by watching eyes—but to where was I walking thus?

To whom.

And who was I? Thought followed thought with fluent skill, I grasped in an instant the particular dissonance between my state and that of this so distinguished throng, for each of them had a history, a family, decorations of one kind or another, the same nobility won from intrigues, betrayals, and each paraded his inflated bladder of sordid pride, dragged after him his personal past like the long, raised dust that trails a desert wagon, turn for turn, whereas I had come from such a great distance, it was as if I had not one past, but a multitude of pasts, for my destiny could be made understandable to those here only by piecemeal translation into their local customs, into this familiar yet foreign tongue, therefore I could only approximate myself to their comprehension, and with each chosen designation would become for them a different person. And for myself as well? No … and yet, nearly so, I possessed no knowledge beyond that which had rushed into me at the entrance of the hall, like water when it surges up and floods a barren waste, bursting through hitherto solid dikes, and beyond that knowledge I reasoned logically, was it possible to be many things at once? To derive from a plurality of abandoned pasts? My logic, extracted from the locoweed of memory, told me this was not possible, that I must have some single past, and if I was the daughter of Count Tlenix, the Duenna Zoroennay, the young Virginia, orphaned in the overseas kingdom of the Langodots by the Valandian clan, if I could not separate the fiction from the truth, then was I not dreaming after all? But now the orchestra began to play somewhere and the ball careened like an avalanche of stones—how could one make oneself believe in a reality more real, in an awakening from this awakening?

I walked now in unpleasant confusion, watching my every step, for the dizziness had returned, which I named vertigo. But I did not give up my regal stride, not one whit, though the effort was tremendous, tremendous yet unseen, and given strength precisely for being unseen, until I felt help come from afar, it was the eyes of a man, he was seated in the low embrasure of a half-open window, its brocade curtain flung whimsically over his shoulder like a scarf and woven in red-grizzled lions, lions with crowns, frightfully old, holding orbs and scepters in their paws, the orbs like poisoned apples, apples from the Garden of Eden. This man, decked in lions, dressed in black, richly, and yet with a natural sort of carelessness which had nothing in common with artificial, lordly disarray, this stranger, no dandy or fop, not a courtier or sycophant, but not old either, looked at me from his seclusion in the general uproar—just as utterly alone as I. And all around were those who lit cigarillos with rolled-up banknotes in front of the eyes of their tarot partners, and threw gold ducats on green cloth, as if they were tossing nutmeg apples to swans in a pond, those for whom no action could be stupid or dishonorable, for the illustriousness of their persons ennobled everything they did. The man was altogether out of place in this hall, and the seemingly unintentional deference he paid to the stiff brocade in royal lions, permitting it to drape across his shoulder and bathe his face with the reflection of its imperial purple, that deference had the aspect of the most subtle mockery. No longer young, his entire youth was alive in his dark eyes, unevenly squinting, and he listened or perhaps was not listening to his interlocutor, a small, stout baldhead with the air of an overeaten, docile dog. When the seated one stood up, the curtain slid from his arm like false, cast-off trumpery, and our eyes met forcefully, but mine darted from his face in flight. I swear it. Still that face remained deep in my vision, as if I had gone suddenly blind, and my hearing dimmed, so that instead of the orchestra I heard—for a moment—only my own pulse. But I could be wrong.

The face, I assure you, was quite ordinary. Indeed its features had that fixed asymmetry of handsome homeliness so characteristic of intelligence, but he must have grown weary of his own bright mind, as too penetrating and also somewhat self-destructive, no doubt he ate away at himself nights, it was evident this was a burden on him, and that there were moments in which he would have been glad to rid himself of that intelligence, like a crippling thing, not a privilege or gift, for continual thought must have tormented him, particularly when he was by himself, and that for him was a frequent occurrence—everywhere, therefore here also. And his body, underneath the fine clothing, fashionably cut yet not clinging, as though he had cautioned and restrained the tailor, compelled me to think of his nakedness.

Rather pathetic it must have been, that nakedness, not magnificently male, athletic, muscular, sliding into itself in a snake’s nest of swellings, knots, thick cords of sinews, to whet the appetite of old women still unresigned, still mad with the hope of mating. But only his head had this masculine beauty, with the curve of genius in his mouth, with the angry impatience of the brows, between the brows in a crease dividing both like a slash, and the sense of his own ridiculousness in that powerful, oily-shiny nose. Oh, this was not a good-looking man, nor in fact was even his ugliness seductive, he was merely different, and if I hadn’t gone numb inside when our eyes collided, I certainly could have walked away.

True, had I done this, had I succeeded in escaping that zone of attraction, the merciful King with a twitch of his signet ring, with the corners of his faded eyes, pupils like pins, would have attended to me soon enough, and I would have gone back. But at that time and place I could hardly have known this, I did not realize that what passed then for a chance meeting of glances, that is, the brief intercrossing of the black holes in the irises of two beings, for they are—after all—holes, tiny holes in round organs that slither nimbly in openings of the skull—I did not realize that this, precisely this was foreordained, for how could I have known?

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Mortal Engines»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Mortal Engines» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Mortal Engines» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.