such an unconventional career path constituted proof of how the Big Army had changed since the fall of the Berlin Wall.

———

“I’ll never be a general, so this is the only band I’ll ever have,” Wilhelm remarked, as the small border force band banged out a variation of a Red Army tune from the 1940s. The detritus of a dead empire was apparent in other ways, too, at this regimental outpost. Near the parade ground was a row of rusted and wheelless armored personnel carriers from the days

when the Soviets had used Mongolia as a buffer against China, in the wake of the Sino-Soviet split. Out here there was no way to crush these vehicles, break them down, or recycle them in any way. They were literally ruins of a gone age.

After reviewing the band, we packed our gear into the UAZ and continued our journey northeast along the Chinese border. The plan today was to stop at a few ovoo s en route to Shiliin Bogd Uul, an extinct volcano considered by the Mongolians to be holy. “What’s the point of all this, militarily speaking?” I half complained to Wilhelm.

“None,” he replied, smiling. “Col. Ranjinnyam and the others want us to climb the holy volcano. It’s real important to them, so we have to do it. These are the kinds of things the Chinese and Russian defense attachés would never do with the Mongolians. That’s why they trust us. Yesterday was a Roy Chapman Andrews day; today will be a Bruce Chatwin or Peter Fleming day.” Yesterday, he meant, was given over to Boys’ Own activities of hunting gazelles and target shooting. Today we would savor the aesthetics of landscape and culture. [28] But it must be said that Fleming was no slouch at hunting. Much of what he ate in his journey across China he had shot himself. He would die tragically in a hunting accident in Scotland at the age of sixty-four.

We stopped to inspect a pair of shattered Turkic statues, standing like mysterious totems in the midst of the desert. They may have been built by the Hsiung-nu (Huns) and dated apparently to the early centuries of the Common Era. No one seemed to know. The guidebooks contradicted each other. We also came upon a statue of Toroi-Bandi, a local bandit who had harassed the Manchu Chinese. Symbolically, the statue faces the Chinese border. It had been turned into a holy site next to an ovoo, to which we gave offerings.

We then passed a region of giant crescent-shaped sand dunes rising over a felty marshland. The Gobi was the most varied desert I had ever seen. It had everything: dunes and marshes; hard dirt steppes and gravel plains; pure sandy desert and slag heaps; clay hills, mountains, and glacial slopes. In the late afternoon we arrived at the sacred volcano of Shiliin Bogd.

The gaunt, hump-shaped rock that we ascended granted a view to the south and east of a shimmering desert, knobbed with the ranks of many dead volcanoes and scarred with moraine ice, as if the moon were coated in sawdust with the black rims of its craters sticking through. This was the

western edge of Manchuria, the point where the last vestige of the Western classical world—with its Hun, Turkic, and Mongolian hordes that had ravaged Rome and its shadowlands—gave way to Sinic civilization. “It is a paradise for wolves,” Col. Ranjinnyam said.

We circled the ovoo at the summit three times, then prepared a barbecue with the ducks that Col. Ranjinnyam had shot earlier in the day, and which Wilhelm had dressed. In a toast to Wilhelm, Col. Ranjinnyam said that he respected the American and Russian armies above all others “because they suffered and won World War II. I want soldiers like Genghis,” he went on, “but, of course, without the cruelty of those days.”

At the end of the meal we passed around hot rocks from the barbecue to juggle in our hands, a local tradition that Mongolians claim is good for the upper-body joints. Then we took the shoulder blade of a sheep and punched a hole in it, so that no one could cast a spell on us. Wilhelm enthusiastically explained all these traditions to me. “I love my job,” he repeated.

———

Completing our visit to the border regiments, Col. Ranjinnyam accompanied us in his UAZ for the long drive to the town of Choir, located in central Mongolia, southeast of Ulaanbaatar. Outside Choir was a deserted Soviet air base that Wilhelm wanted to inspect, with an eye toward its future use by the United States.

The two-mile-long runway needed only modest repairs and could handle any kind of fixed-wing aircraft in the U.S. arsenal. Beside it was a long line of hardened aircraft shelters, reinforced-concrete bunkers in the shape of semi-pyramids to protect fighter jets from aerial bombardment. A gigantic sign proclaimed “Praise to the Communist Party Central Committee.” The Choir base had been built in the 1970s, a consequence of the Sino-Soviet split a few years earlier. It constituted a forward front for the U.S.S.R. in a possible conflict with China.

Why in the world would the U.S. ever need a base in Mongolia? one might ask. In the 1990s, Wilhelm had thought the same thing in regard to Tajikistan. Then came September 11, 2001, and back-of-beyond Tajikistan, with its southern border facing Taliban-controlled Afghanistan, suddenly became a possible staging area for U.S.-led coalition operations. “That’s when I learned never to say ‘never,’” Wilhelm said. With Mongolia’s eastern border only five hundred miles away from North Korea across Manchuria, in an unpredictable, fast-changing strategic environment an air base here could be an asset.

There was no thought of making Choir an American base, the way it once had been a Soviet one. Rather, for a relatively small amount of money the runway and a building or two might be repaired and kept up, so that American planes and Air Force personnel could use them at any time. Given the political instability throughout Central Asia, the Pentagon was intrigued by a Eurasian “footprint” strategy in which the U.S. would have basing options everywhere, without having a significant troop and hardware presence anywhere.

Choir itself was nothing but a series of skull-like concrete tenements surrounded by steppe. A building complex that had once housed 1,850 Soviet military families, including a theater and shops, had been stripped of all its windows and heating pipes. “It used to be so lively,” said Maj. Altankhuu, “it was the place where all Mongols wanted to go in the evening.”

Overlooking a field of broken glass, where the last tenement block met the flat and empty Gobi, was a concrete statue of a generic Soviet commissar strutting forward in the sneering, aggressive style of Lenin. The statue of Father Soviet had begun to flake and crumble, though, on account of its gargantuan size, it might be here forever: the ultimate Ozymandias, with only a few yaks and stray dogs to admire it.

The statue brought to mind not just brutality and domination, but also cheapness. “Another thing constructed by a high school shop class,” Wilhelm observed, laughing.

“We should be careful of our own ambitions,” I said. “We don’t want to end up like the Soviets.”

“There is nothing we need to build here,” he answered, “except relationships.”

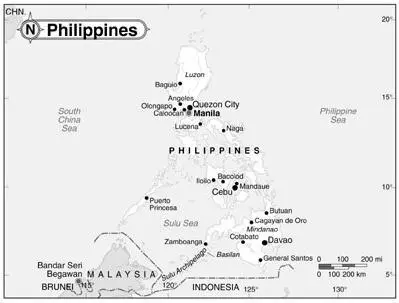

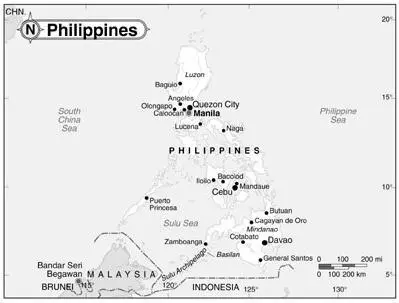

CHAPTER FOUR

PACOM

THE PHILIPPINES, SUMMER 2003

WITH NOTES ON THE PHILIPPINES, 1898–1913

“Terrorists used these poor, shantyish, unpoliceable islands as hideouts…. Combating Islamic terrorism here carried a secondary benefit: it positioned the U.S. for the containment of China.”

Читать дальше