Cabrera brought me daily casualty reports from the internecine guerrilla fighting between the FARC and ELN, which in his mind was good news: let the narco-terrorists kill each other. He told me about a new class of improvised claymores: glass and nails stuck in melted tar; barbed wire wrapped around dynamite; bolts and nails sunk in fertilizer inside a milk can. Then he told me about how the ELN had hired a top lawyer to get their Venezuelan explosives expert released early from prison.

One day Cabrera introduced me to four members of a Colombian army motorcycle platoon that investigated car and bicycle bombs. They were solid little men in their early twenties. Their faces were the hue of the soil, with the broad features and impassive expressions of indigenous Indians. Sitting on camp chairs amid the sandbagged walls of the Special Forces compound, they explained that they were volunteers from Bogotá and Tolima, because nobody local could do their job without endangering their families. The week before there had been five of them. Now one was dead. They had arrived at the scene of a car bomb. After they moved the crowd away and cordoned off the area, a second bomb had gone off, sending one of them ten meters in the air. He lost his torso and died on the spot.

While these four soldiers were risking their lives daily, other Colombian soldiers were secretly helping the terrorists. I learned of an incident a few days earlier. A Colombian army unit was notified that it would be dispatched to arrest several guerrilla leaders at a meeting in Saravena. Some of the Colombian privates then made calls from their cell phones. When the unit arrived at the site, the tables and chairs for the meeting were set up but no one was there. Having presumably got word of the raid, the guerrillas had fled.

“We’ve told the Colombians,” Ferguson said, clearly exasperated, “that we’re not going to get anywhere in this war, despite the training we’re giving their counter-guerrilla battalions, if they can’t even confiscate cell phones from their privates. But they haven’t done it.”

I thought of what the intelligence operative had told me in Arauca: Uribe’s tough anti-guerrilla rhetoric had little follow-through in the field.

———

The following day I observed training. The purpose was to stage an ambush. But before that could be done, a security perimeter and rally point near the ambush site had to be established.

Sgt. Dave Ogle of Spokane, Washington, was standing knee-deep in bramble so thickly matted and dense that visibility was only a few feet. Members of the Colombian army’s 30th Counter-Guerrilla Battalion were walking single file ahead of him. Setting up a 360-degree security perimeter is easy in an open field, but it took skill in this endless thicket. Having gotten his Colombian troops in a massive circle, each soldier lying on the ground, facing out from the center, covering twenty degrees or so with his rifle, unable to see each other yet aware where all the others were, Ogle next had them practice finding an objective rally point, a place which was “out of sight, sound, and small arms range of the objective area.” 28

The plan was to ambush a pickup truck on a nearby dirt road. The day before, the Colombian army had accomplished the task smoothly. This time Ogle and the other sergeants added a surprise: a Green Beret was hidden under an old blanket in the back of the pickup. As soon as the Colombians jumped out of the bush to surround the pickup, the Green Beret shot the squad leader, who dropped his M-60 machine gun. But none of the other Colombians assumed command; nor did any of them think to retrieve the M-60 from the dead man.

“Both the assumption of command and the gun died along with the commander,” Sgt. Ogle remonstrated afterwards in Spanish. He ended in an upbeat manner, though, with the necessary clichés: “Do your best. Do what’s right. Do what you’re supposed to do.”

He and the other sergeants stayed out with the trainees through the worst of the muggy midday heat. At dusk we plodded back to the barracks, where under the fluorescent lights, Sgt. First Class Javier Martinez of Oxnard, California, who had wanted to join the Army since he was six, mentioned that the hardest field maneuver to teach the Colombians was charging directly into an ambush. “Directly assaulting an ambush line is counterintuitive,” he explained. “It demands a lot of self-confidence in your team and in your commanding officer. But the technique was used successfully in Vietnam. You can find it in the Ranger Handbook. ” 29

“Yeah,” someone responded. “But how do we get these guys to believe us, if we’re not allowed to go out on patrol with them against the FARC and ELN? Every time they go out on an op without us, we lose face.” Only if they were attacked could the Green Berets violate the rules of engagement.

Suddenly we heard gunfire. I turned my head. Capt. Ferguson frowned and said, “It’s just night practice at the range. We should be so lucky.”

———

Policing the world meant producing a product and letting it loose, Maj. Gen. Sid Shachnow had told me back in North Carolina. That product had been produced all right, but it hadn’t been let loose in Colombia. The American contractors taken hostage from that downed plane in southern Colombia were still being held captive two years later—a situation that might have been avoided had the two A-teams gotten permission to deploy to the crash site twenty-four hours earlier. As in Vietnam in the early 1960s, the effect of Special Operations Forces was blunted by the unwillingness of policymakers to utilize them more effectively as a policy instrument. [21] This is one of the themes in Shultz’s The Secret War Against Hanoi .

It was partly because of such timidity that the Johnson administration had been left with no other options than to escalate the war in Vietnam with conventional troops, or get out completely.

In Colombia, though, as the months rolled on, some forward steps were made. President Uribe reclaimed rebel areas, thanks to the training provided by Green Berets. The level of violence dropped somewhat, and Uribe, who had lost none of his political courage, went on to become the most popular leader in modern Colombian history. Imperial progress was slow and imperceptible. It could not be measured in news cycles, and was always subject to reversal.

The problem for the U.S. military, even at the tactical level of infantry, was that its capabilities were simply too potent for the restrained diplomacy born of an age of media intrusion. Thus the challenge was to go unnoticed. The next place I went, I saw what one man could do when given absolute freedom, and when nobody was looking.

CHAPTER THREE

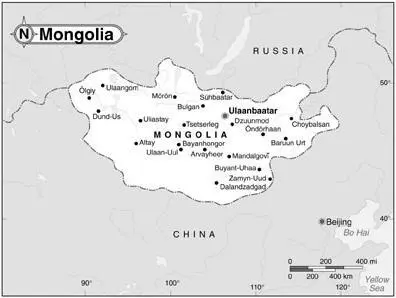

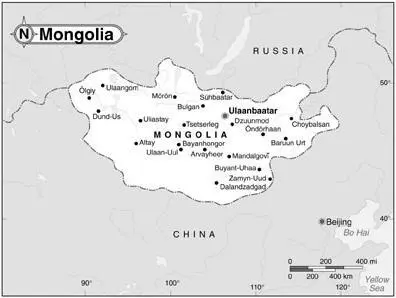

PACOM

MONGOLIA, SPRING 2003

WITH NOTES ON MACEDONIA, BOSNIA, AND TAJIKISTAN

“Mongolia was a trip wire for judging future Chinese intentions…. Col. Wilhelm was determined to make the descendants of Genghis Khan the ‘peacekeeping Gurkhas’ of the American Empire.”

In the early spring of 2003 an American-led host, spearheaded by the First Marine Expeditionary Force (I MEF) and the Army’s 3rd Infantry and 101st Airborne divisions, captured Baghdad, racing from Kuwait across 350 miles of hostile Mesopotamian desert to the Iraqi capital, seizing it and other cities along the way, and doing so with greater speed and efficacy than German Panzer divisions moving across Russia in 1941 and the Israeli Defense Forces moving across Sinai in 1967. Because conventional war played to the strengths of the Pentagon brass, they outdid the military achievements of Xenophon at Cunaxa in 401 B.C. and of Alexander the Great at Gaugamela in 331 B.C., both of which lay along the invasion paths. The three-and-a-half-week campaign would be comprehensively documented by hundreds of journalists who were implanted with the Marine and Army divisions. [22] This included my colleague at The Atlantic Monthly, Michael Kelly, who gave his life for the enterprise. Embedded with the 3rd Infantry, he was killed April 3, 2003, on the outskirts of Baghdad.

Читать дальше