I remember delivering Ilke or Adriënne or Bernadette to her front door, wherever that was. There is a vague recollection of the offer of a nightcap — no thanks, I’ll be getting along now. I probably did not mention that my old life, now irreparably improved, was waiting for me at home. She had taken it away from me, but not for good, and in the meantime it had only appreciated in value.

5

It was three in the morning. I had a spring in my step, like a freed prisoner. Took the stone steps up to the front door in two, three bounds.

I assumed I had taken the wrong key from my pocket, the one to my flat in Duivelseiland, because it didn’t fit. The teeth glanced off a shiny new cylinder lock that had taken the place of the old, dull one. The copper plate maliciously reflected my fingers holding the useless key. Around it, some of the canal-green paint had been chipped off, undoubtedly during the replacement, and these chips now lay at my feet among some wood splinters and two minuscule piles of sawdust. Apparently no one had walked through it yet. The new lock must just have been installed. I stood there, half paralysed, looking incredulously at the paint chips, the splinters and the sawdust. Once again, everything was turning out differently than I had been led to believe. So this was what being in love against could lead to. The fatal blow, right behind my ear.

I trudged down the steps and walked backwards as far as possible across the street, to the edge of the canal. I nearly had to pull my chin upward with my hand before I dared look. There was light in the sitting room, whose white curtains were drawn — which usually meant, at this late hour, that someone was home.

And there was someone at home. A Chinese shadow play was being projected against the white pleats, two wavy figures approaching each other. It was just like an old Hollywood film, with a private eye crouching behind a garbage can and the husband leaning against a streetlamp, nervously smoking and sprouting horns. The two figures stopped for a moment, and then wrinkled intimately through one another. My wife and the Borderless Correspondent, no doubt: I recognised Miriam by the terraced way she put up her hair, whose contours did not get lost in the shadow play.

Goddamn it, how could I have let myself be fobbed off to a distant neighbourhood, so that they could, undisturbed, carry out their plan to shut me out once and for all? Someone this naïve did not deserve any better.

And then: well well, a third silhouette appeared. Tall, masculine, with a large head cut off by the top of the window frame. An object was passed from one outstretched shadow-hand to another.

Ach, Minchen, Minchen, it didn’t have to come to this. My Friday night bliss shot to hell, the bliss that wasn’t to be mine. And Miriam? She had simply dragged in the happiness that hadn’tjust come naturally, and changed the locks behind her. No cutting corners.

But why such a roundabout charade? She could have just left me, which would have been bad enough. Why add insult to injury with such hard, durably executed symbols? Not to mention the after-hours surcharge. Slamming the door in someone’s face was apparently not enough these days. If the poor sucker locked outside had the skin of an elephant and stayed waiting patiently for someone to open the door, then he could just see how a fine drill bit bored through the wood …

Meanwhile, damn it, I stood there in front of a locked door, which meant that I had underestimated the wiles of the other party after all.

Perhaps I had clung too much to the notion that Miriam was out of love with me , rather than in love with him, the other. The possibility that she was about to break off with Our Man in Africa did not mean I was automatically back in her good graces. It was my misjudgement to think that this whole ‘in love against’ thing was in itself something temporary. I no longer ruled out the prospect that she was so totally and fanatically out of love with me, and that, regardless of any other man, I was being unceremoniously dumped, right here on her front stoop.

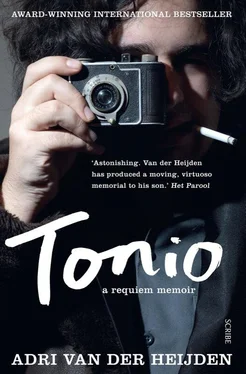

6

I was reminded of a morning shortly after Tonio was born. Up early, I looked over at Miriam, my sleeping treasure, in the early morning daylight. Entirely unexpectedly, in a kind of wavelike slinking motion, her hand crept over the bottom sheet toward my head. A five-legged creature. Near my chin she scratched the light-blue fabric with her index finger, emphatically, as though she were trying to warn me of something, or wanted to gently wake me up to put an end to my snoring.

I wasn’t snoring, nor was there any danger of it either, as far as I can recall. The hand, its fingers dirtied with an excess of pigment, pulled back, but quickly scampered back to resume its scratching.

‘Minchen …?’

I had to repeat her name a few times before she answered with a soft groan, from way down deep. She slept on. Except for her hand, which kept creeping toward my face, again and again, to resume the scratching. I did not know what it meant, but the gesture was strangely moving. Later, when she was feeding the baby, I imitated her manual drill, but she did not believe me.

Those funny things of hers I’d never see again. Not to mention all the wonderful things Tonio would do that would likewise be denied me from now on. Like just recently, when he raised a finger and called out: ‘There come the knights!’

I went back up the steps of the stoop and rang the bell. In the still of the night you could always hear it ring upstairs. But not now. Of course, when we went out, Miriam would usually turn off the bell so as not to startle the cats, but now that she was apparently home, its off-ness could only mean yet another way for me to be shut out, shunned.

I wailed her name through the letter slot, perhaps more as a farewell than an attempt to elicit mercy. More or less at once, the upstairs door to the stairwell opened and I heard the downward cadence of footsteps.

In retrospect I have to conclude that those quick steps, Miriam’s trotting downstairs, said it all: that we belonged together, and would stay together. That patter on the steps meant that my feelings were not to be hurt. She arrived, out of breath, to welcome me back. A fresh start, but this time a level higher.

She was almost there. I knelt at the door, my eyes level with the letter slot, my thumb holding the flap open.

‘Adri, it’s not what you think,’ she called out.

It was not what I thought. The door swung open. (I don’t know why, but I was reminded of the first time she opened a door for me. I stood on her front step with a bottle of Dimple whisky under my arm. ‘I never drink whisky.’ — ‘Madam, I never eat muscatel grapes.’)*

[* A line from The Count of Monte Cristo spoken by the hero, Dantès (the count of the title), claiming that he cannot eat any food in the house of his enemy.]

‘First tell me what I do think.’ (If it could be everything I didn’t think, that would be enough to quieten the hell.)

‘Come upstairs and I’ll explain.’ Her face was so overcome by embarrassment that I almost felt sorry for her. ‘Don’t just stand there.’

‘I don’t know what I’ll find upstairs.’

‘I’ll explain everything.’

Her chagrin reversed the roles. At first, I was planning to play the injured party and skulk off, but in the end I followed her up the stairs, determined to make a scene.

7

I could hear men’s firm voices through the open door to the flat. I held back on the landing to listen. I could have been mistaken, but it sounded like the discussion was about hinges and door furniture in medieval churches — not exactly a subject related to Africa.

Читать дальше