6

We were dropped off at the campground reception, which was run by the Dutch couple who rented us the maison décole . We’d be taken to the house later in a minivan once it was available, but for now we could wait at the campground’s outdoor café. The bus drivers were already there. Instead of having a lie-down they went straight for large glasses of Heineken from the tap, while the departing campground guests dragged their luggage to the coach, which would leave in an hour’s time for the Netherlands — with the same two drivers at the wheel.

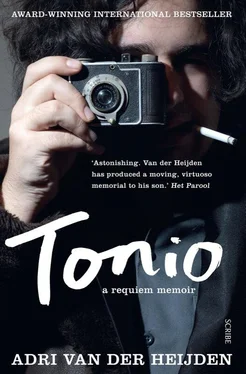

Miriam and I were draped over our chairs with sleep deprivation, but the café itself was abuzz. Two girls of around ten, one a bit bigger than the other, descended with squeals of excitement upon Tonio, who couldn’t really walk yet and tried to keep himself standing by grasping table legs and chair backs. No problem: the little ladies took turns lifting him from the ground and carrying him, happy as could be, hither and thither. A real-life baby doll, with a real-life full nappy, no less — their holiday enjoyment was sealed. Only a pity that there weren’t two of these golden-locked cherubs.

Meanwhile, a distinguished-looking, white-haired older man appeared on the scene carrying a camera. I had already spotted him when we arrived: he had probably gone back to his tent to fetch his camera. He approached our table, almost quaking with emotion, and pathetically beseeched us if he could take a picture of Tonio.

‘Honest to goodness,’ he said hoarsely, ‘I have never seen such a beautiful child. I simply must photograph him.’

‘Go on then, just one,’ I said.

The man commanded the little girl who had just lifted Tonio up over her head to put him on the ground. He clamped himself to her leg and smiled at the camera, just as he’d been taught. The photographer, in all his creakiness, threw himself to his knees in front of Tonio and took a close-up. He groaned, but I suspect it had nothing to do with his uncomfortable position, because he kept on clicking. He shifted his knees.

‘Such a beautiful child,’ he cried. ‘I just can’t get over it.’

Miriam and I glanced at each other. I got up, went over to the man and said, while laying a hand on his shoulder: ‘That’s probably enough, sir. Why don’t we let the girls play with him now?’

I helped him up. He was teary-eyed. Another photo of Tonio, who was back in the arms of the other little girl.

‘If you’ll just give me your address,’ the man said, ‘I can send you a few prints. Here’s a pen.’

I felt the sleepless night buzzing through my head. Was I seeing danger at every turn? Was the whole world out to threaten Tonio?

‘Later,’ I said. ‘We’ve only just arrived.’

‘That’s just it,’ said the man. ‘I’m just about to go back to Amsterdam with the bus.’

‘Then if I might give you a bit of advice,’ I said, ‘keep an eye out that the drivers take enough rests.’

Another Dutch campground guest rescued me, taking me for the Dutch writer and former chess champion Tim Krabbé. ‘I’ve always wanted to play chess with you,’ he said. ‘Can I invite you for a game tonight? Here on the terrace. I’ve got everything with me. A timer, too.’

7

The girls were the Van Persie sisters from Rotterdam. Lily (nine) and Kiki (going on twelve). They were staying at the campground with their divorced mother and younger brother Robin, who was just about to turn six.* It was mostly Lily, with her broad mouth and uncombed curls, who took Tonio under her wing, and with a gusto I had seldom seen in a girl that age. As soon as she laid eyes on Tonio, she would insist he be removed from his pushchair. She agreed to stay within sight of us, his parents, as she carried the tyke to and fro, but refused to give him back. Tonio was too heavy for her girlish body; he kept sliding down her chest, and Lily would then shimmy him back up as far as he’d go. With any luck, Tonio would throw his arms around her neck, giving her a bit of extra grip.

[* Robin van Persie would later become a well-known soccer player and a member of the Dutch national team, and is at present a star striker for Manchester United.]

Tonio loved all the attention and cuddling. With his head up close to Lily’s, his laugh was broad and drooly, and he panted with flirtatiousness. And the important thing was: he and Lily were on the same wavelength. It was as though, their heads close together, they were continually in conversation.

Lily had the distinct misfortune that Tonio learned to walk during those first weeks of the holiday. As soon as he realised that his place was down there with both feet on the ground, he would thrash wildly in Lily’s arms until she gingerly set him down — and not just in the hard grass, where he’d soon plop onto his rear, but near a large object, a table or chair, which he could hold onto as he walked around it. Best of all were the metal supports of his stroller, because they had wheels — he was mobile.

Kiki and Lily often showed up at the schoolhouse early in the morning, while we were still eating breakfast, to ooh and aah in admiration as Tonio’s mother pushed dice of Laughing Cow soft cheese into his mouth. Soon enough the girls were allowed to unwrap the foil themselves and feed Tonio the bite-sized cheese cubes. His eyes sparkled, his drool became milky from the white cheese. All we had to do was watch out he didn’t get overfed.

Sometimes the sisters brought their little brother Robin with them, who never spoke and always wore an angry little pout. After breakfast, Tonio resumed his walking lessons behind the stroller under the tutelage of Lily and Kiki. He was now between thirteen and fourteen months old.

In my recollection, I see Robin leaning up against the outside of the schoolhouse, one foot up against the wall. Surly and haughty, he watches the movements of the toddler, who enjoys his sisters’ full attention. I sit at the picnic table under the apple tree, pretending to be absorbed in yesterday’s already yellowed newspaper, but I cannot take my eyes off the scene before me. Tonio has the tendency to push a bit faster than the wheels can furrow through the rough grass, so that he leans back slightly and easily falls over. He’s got the hand-grips firmly in his fists, above his head, so that as he topples over backwards he pulls the pushchair on top of himself.

‘Oof.’ The girls rush to prop him back up. At Tonio’s eye level is a shopping net, strung onto the frame by an elastic cord, with tissues and extra Pampers. Every time he falls over backwards, the nylon netting falls over Tonio’s face, like a loosely woven veil, and he doesn’t like it much. Not much time for crying, though: practice makes perfect. His dismay is limited to a brief whine while his fingers tug at the butterfly net. Kiki and Lily leap to the rescue. Lily takes advantage of the situation by scooping Tonio up and nuzzling him. He tries to wriggle away: there’s work to be done.

Robin’s stance hovers between childish contempt (pff, he can’t even walk) and an equally childish jealousy (my sisters don’t give me the time of day, but they’re all over that clumsy sprog). He, Robin, is not only good at walking, fast and slow, but he can creep, jump and climb, too. ‘Robin’s problem is,’ says Kiki superciliously, imitating her mother, ‘that he has no concept of danger.’

Tonio is back up on his feet, and screeches as he pushes the stroller. Again he’s learned something new: he wrenches and jerks the stroller over a stubborn tuft of grass and walks on. The girls follow him with arms extended, prepared to catch him should he fall.

I am worried about the fearsomely large wasps here; they fly close to the ground, as though they’re too heavy for their wispy wings. They look savage, and I imagine their stinger dripping with poison. I have already chopped one in half with a breakfast knife; it was pestering Tonio and I thought I was giving it a quick, painless death. Horrified, I saw how both halves stayed alive: the front half propped itself up on its wings, the back half — call it the weapon-wielding half — wobbled off, carrying the defeated stinger with the remaining legs.

Читать дальше