My father-in-law, my sister, my brother, with wife and child: they were all free on Monday 12 July, the day after the World Cup finals. My mother-in-law, who had so vociferously refused even to shake her ex-husband’s hand at the funeral, would have to go another time. Even then, we couldn’t discount that she would raise a stink about the name ROTENSTREICH on the gravestone. Dealing with her was a matter of never-ending, and usually fruitless, diplomacy.

7

Before the finals, Miriam served deep-fried calamari with the drinks.

‘The guy at the Albert Cuyp market said it was one of Paul’s tentacles. Y’know, the German octopus that predicts football results. By … how’d he do it again? … picking mussels out of the right box, something like that.’

‘And you just toss a tentacle of the oracle into a deep-fryer? That’s tempting the gods.’

‘Nah. Octopus. Paul predicted that Spain would win. Now he’s been rendered harmless. At the Cuyp, they cut the bad mussel out of him and threw it to the gulls. Spain’s gonna lose.’

‘These rings have an alarming crunch to them.’

‘I sprinkled coarse sea salt on top.’

Every moment that, thanks to a bit of diversion, I don’t have to think My life is ruined for good is a plus. At the same time, right after such a moment of distraction, I am convinced that I cannot let go of the thought of my ruined life for even a second. This would be my permanent tribute to Tonio. His life cut short for good, and his future definitively behind lock and key? Then I must be continually confronted with the ruination of my own existence. My focus must not be allowed to waver.

In that duplicitous frame of mind, I take my place in front of the TV.

8

I could keep telling myself that I couldn’t care less who won, but I was at least conscious of the subdued atmosphere after the anticlimax. I had expected the spectators to leave Museumplein in a jeering protest as they made their way to various flashpoints throughout the city: the Spanish consulate, for instance, and any number of Iberian restaurants. I pricked up my ears, but the streets were quiet — there was no noisy grousing by streams of passersby, no vuvuzelas.

The image arose of a crowd, stunned and silent, remaining behind en masse.

‘I’m just going out.’

Herds of dejected football fans were indeed hurrying home: mute, on whispering and lisping shoe soles. In this anonymous darkness, which had erased our national identity, I dared to walk unguarded outdoors. I ambled against the stream to the end of the street. The interior of Café Welling, where the television had already been switched off, looked so sombre you’d think they’d just come from the funeral of one of their regulars. A small group sat outside, smoking.

Museumplein made me think most of one of those third-world garbage dumps, where paupers send their kids to root around for usable rubbish. But these manure pits are usually not lit up at night by floodlights and giant projection screens (now imageless). The place was nearly entirely deserted. A ragged, glittery carpet of trash (beer cans, water bottles, lots of light-blue plastic, crates, orange bits of clothing) concealed what used to be the grassy commons. You looked up almost automatically to check for buzzards. Only nose-diving gulls.

Two amateur scavengers, about ten years old, were collecting discarded vuvuzelas, perhaps in the hope of creating a last-minute market in the run-up to the team’s homecoming welcome the day after tomorrow. They were clever enough to try them out first, braving the residual spit of strangers, just to make sure they could get a lugubrious honk out of the thing.

The sound of crushed aluminium and splintered plastic underfoot had not entirely dissipated: here and there, groups of hangdog supporters were leaving the area, aware that despite the profound loss, in four years’ time there’d be the opportunity to get even. I was immune to it. What did hit me was the setting of the disgrace: it only reminded me, together with those ten-year-old scavengers, of my own loss. Missing Tonio could be augmented in myriad ways and with myriad attributes.

9

Today, the 12th of July, we would add the newest acquisition to Tonio’s rock collection. Not in the glass display-case in our living room — its dimensions did not allow for that. This monster of Belgian bluestone was to be exhibited in the open air, at Buitenveldert Cemetery. I had wanted to have them incorporate a piece of lapis lazuli, Tonio’s favourite, into it, but this was problematic for the stonecutters, so we dropped it.

The municipal sanitation department had already started clearing the debris from Museumplein that very night. When I took my timid early-morning walk, they were still busy cleaning — anything to provide a spotless foundation for the next day’s homecoming, so that a new carpet of garbage could be laid. Win or lose, the screaming must go on. Even the city government had already decided there would be a canal parade. This way, they hoped, by some alchemistic trick, to convert defeat into victory. Bring a million orange-clad provincials by train to the capital. Have them throng the players’ boat, from bridge to bridge, and from canal wall to canal wall. All that honking and orange smoke will magically transform disgrace into triumph. The new mayor cashed in on it: his inauguration was ratified with two streetfests in a single week. Public misconduct, provided it was cloaked in the national colours, was okay.

10

‘Say you lost your wife or your son. Would you keep on writing?’

If someone asked me this before Whit Sunday 2010, my answer would be: ‘Of course not. They are both my muse. Tonio a male one. I do it first and foremost for them. Aside from the question whether there would still be any point in writing, I wouldn’t even be able to.’

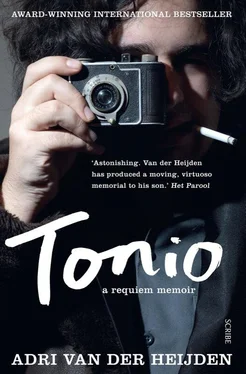

And yet, since the end of May, it’s Tonio who in fact keeps me writing. Every day, from ten-thirty in the morning till five in the afternoon, without a lunch break. It is more an obsessive ritual than voluntary labour. Writing for and about him is the best way to get as close to him as possible, the person he was and the absentee he now is, to talk to him and sit in silence with him. In this way I keep him alive, and when my work is finished, this requiem can, in a dialogue with the reader, keep him alive a while longer.

But after that? Of course, I can say: it’s my job, and seeing as we’ve decided to stay alive … It can never be solely a matter of breadwinning, otherwise I’d have chosen a different profession, with a bit more to show for itself at the end of the workday.

The real question is: what to write after this? My current subject is a kind of pitch-black marvel that has crossed my path. A one-off thing, seeing as there are, thank God, no more children of my flesh and blood to be sacrificed. It seems likely that this will overshadow all subsequent topics.

Maybe I should just wait and see. A fruitless void or …

I have no other answer to this terrible loss than to write about it — only to discover along the way that writing is no answer either, because there was no question. It makes the loss all the more chilling: that no question has been formulated, only an exclamation mark like a razor-sharp icicle.

You could turn things around, and bury the loss, but that does not provide an answer either.

11

At ten o’clock, I went upstairs to work on my notes. It was stuffy. I had the window next to my desk wide open. There wasn’t much point, as it was windless outside — and now the air lay thick and motionless against the houses, not even syrupy, because that would suggest a kind of current. Just when you thought the sky had never been this dark during the day, it got a shade darker. Everything to bring out the effect of the lightning. The muffled thunder reminded me of the drums muted with black cloths in a Neapolitan funeral procession, like the one I saw in Positano in 1980 when I left Miriam behind ‘to observe my happiness from a distance’. We couldn’t have picked a more suitable day to inaugurate Tonio’s gravestone.

Читать дальше