‘I’d like to leave at four-fifteen at the latest, okay?’ she says, slightly harried. ‘Friday-afternoon traffic, you never know.’

Shave, shower, wash hair — the thought of it puts me off entirely. I lie there on my bed until four, not even reading, and without resolving the issue of the sixteen thousand question marks. If I get up now, there’ll be just enough time to get myself more or less dressed. Every day, I still wear what I pulled on the morning of Whit Sunday: jogging pants and a flannel lumberjack shirt. Well, not always the exact same ones, because things do have to go in the wash once in a while. The raking light has definitively made way for a slowly passing cloud cover, for the strong winds have subsided.

Crossing the street to the car, I realise the gout in my left foot has returned. I walk so little, and not at all outside the house, that I hadn’t really noticed the pain until now. The conventional wisdom that foot gout can be caused by eating red meat and drinking red port was recently debunked in the science section of the newspaper. I don’t care for red meat or red port, but do enjoy clear alcohol, which indeed appears to play a role in the formation of painful crystals around one’s joints. I finally dare to leave the house after all these weeks, and the whole neighbourhood gets to see me stagger to the car.

‘You’re limping,’ Miriam says from behind the wheel.

‘I’m forgetting how to walk, that’ll be it.’

Cornelis Schuytstraat. Willemsparkweg. Koninginneweg … the streets are indeed crowded with Friday-afternoon traffic, but it never comes to a standstill. Only at the main intersection with the Amstelveenseweg does traffic move so slowly that we have to let four green lights pass.

The Zeilstraat drawbridge is open. There is such a confusion of gulls flying every which way above our heads that it’s as though they’ve just escaped from a great big box, of which one flap is propped open. It is a long while before the bridge begins to swing shut.

‘I’m curious how far they’ve got,’ Miriam says. ‘I asked them to wait with the lettering. It looked good on the computer, but we have to see it with our own eyes first.’

‘Did you remember about the hyphen?’

‘There wasn’t supposed to be a hyphen …’

‘That’s what I mean, no hyphen. But did you check?’

‘Now that you mention it … My mind is such a chaotic mess. I wonder if it’ll ever get better.’

‘You can go.’

The barrier arm jerks upward. We cross the Schinkel canal, heading toward Hoofddorpplein. When we cross under the motorway, entering Slotervaart, Miriam says: ‘This is the same route we took the day Tonio was born, in the midwife’s little Fiat. Keep an eye out … there, off to the left, Slotervaart Hospital. That’s where he was born.’

I have not been back since 15 June 1988, but I recognise the building at once. Miriam was so caught up in her contractions that morning that she only realised we were at the wrong hospital once we got to reception. Tonio never tired of hearing this story.

‘Sorry, honey, sorry,’ the midwife kept repeating. ‘My fault. Stupid of me. Sorry.’

It was clear, Tonio, that there was no way we were going to turn around and go to the VU, where you were supposed to be born. The midwife pushed the wheelchair with a groaning Miriam down the hall to the lift. Your father wobbled alongside, one hand on your mother’s neck. The wrong hospital. Miriam a wrung-out wreck in a wheelchair. This couldn’t possibly end well.

‘But it did!’ he’d exclaim. ‘Just look at me!’

3

From Plesmanlaan, we turn right into the bland monotony of Osdorp.

‘Jan Rebelstraat,’ Miriam says. ‘Have a look at the map. I was here once with Nelleke, but that was sleepwalking. It’s close to Westgaarde.’

In a north-west corner of Osdorp, I locate the Jan Rebelstraat, indeed not far from the cemetery.

‘Turn left here.’ This autumnal summer sky makes me just as nervous as this afternoon’s uneasy grazing sunlight did. ‘There it is.’

Miriam drives past what looks like a normal shop window. LIEFTINK BROS. STONECUTTERS — SINCE 1913.

‘Just a sec.’ Miriam turns off the engine, closes her eyes. ‘Help me muster up some courage.’

I undo her seatbelt and pull her close. ‘Think of last time, Minchen, when you were here with Nelleke. You pretended it was a garden centre … shopping for a little something for our back terrace. A bargain from the sale section.’

‘That was then,’ she whispers. ‘It’s harder now.’

The door, complete with jangling bell, makes me think of one of those old-fashioned general stores. The left side of the shop has been made into a life-size imitation graveyard, like on a film set. What doesn’t tally is all that marble, flamed pink and striped pearl-grey, so glossy and unweathered. Nowhere is there a patch of moss or a sprig of grass between the stone chips that fill up the plots.

Grass markers. Slants. Uprights. Combinations of these. I wonder if the names inscribed on them, some of them with gilded letters, have been made up. If so, what about the portraits sunk into the marble — or are they computer composites? The novelist’s ideal playroom.

To the right, a display of pink marble hearts, and toy animals (teddy bears, bunny rabbits) carved out of light-grey marble. Behind that, two desks with computer equipment. On the wall, large boards with typeface examples.

A man of around forty gets up from one of the desks. Miriam apologises that we’re early. Handshakes all round, which we don’t normally do at the garden centre. We assume he recognises our names from the gravestone.

‘No problem,’ the man says.

Early . He leads us to the workshop behind the showroom, where a second man is at work in a hazy cloud of dust. Maybe they’re brothers, but not the 1913 ones. Suddenly, before we’ve prepared ourselves for it, we are looking down on a gravestone, lying flat on its back and supported by wooden trestles — with our surnames on it.

‘I’ll just go get the paperwork,’ says the man who received us. He goes back to the front room.

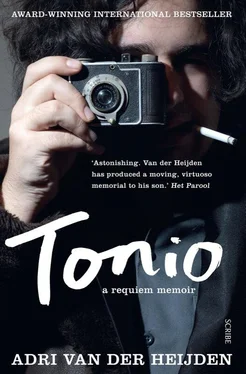

TONIO

ROTENSTREICH –

VAN DER HEIJDEN

I point out the hyphen to Miriam. ‘You see how these things take on a life of their own? It’s as though Tonio, maiden name Van der Heijden, was married to a Mr. Rotenstreich. One little hyphen, and he’s lying in his grave with another identity. With a different gender, even.’

‘Stuff for a thriller,’ Miriam says. ‘Alfred Kossmann coined the term “identity fraud” — that’s where it all started, right? Without my thesis on him, we wouldn’t have come up with the name Tonio.’

‘All right, the thriller opens with an exhumation,’ I say. ‘Reason: an erroneously chiselled hyphen, giving the buried person a mistaken identity. I’ll leave the rest up to you. After all, it’s your last name that …’

‘That what?’

‘That doesn’t belong there.’

‘You can still have them take it off.’

‘Not on your life. Not now that I can finally make good on an old promise.’

The three names, and Tonio’s dates, are printed on a sheet of paper, which is taped to the stone. Everything can still be amended, shifted. The man returns with the paperwork. ‘Check along with me, if you will … The headstone is made of Belgian bluestone … one hundred centimetres high, eighty wide, and eight thick. How do you want the photograph?’

The rectangular plaque with Tonio’s self-portrait as Oscar Wilde etched onto it is, I see only now, is lying loosely on the stone. ‘What are the choices?’ I ask.

‘Anything you like,’ says the man. ‘From medallion to recessed. My personal advice would be: half-sunken into the headstone, so it’s still in mid-relief.’

Читать дальше