When his head grew too full with questions of phenomenological hermeneutics, he would stroll through Jardin des Plantes and sketch the curated flora from far-flung lands, including those from his own. The plants’ structural certainty soothed him in the face of great doubt. On each of his annual returns to Indochina, he would bring back a new specimen for the gardens of La Seule Vérité. Eugenia became his horticultural partner in crime, and together they cultivated a collection of more than two hundred exotic plants that rivaled the great botanical gardens of Saigon. Her surreal chromatic paintings of the flowers hung throughout the house, presenting the unsuspecting visitor with a mildly hallucinogenic experience.

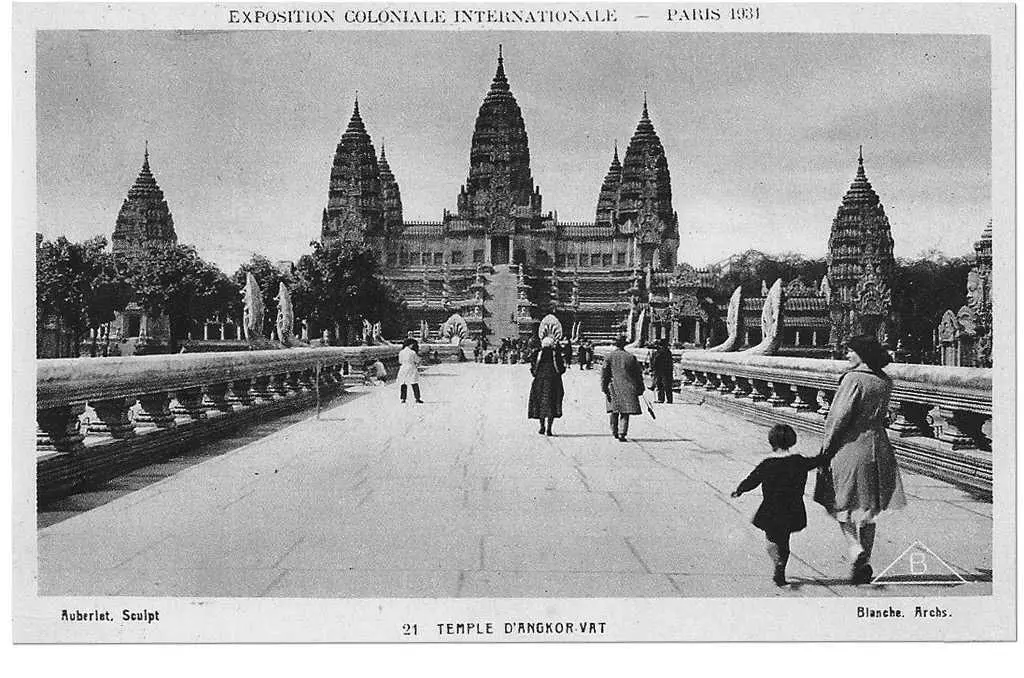

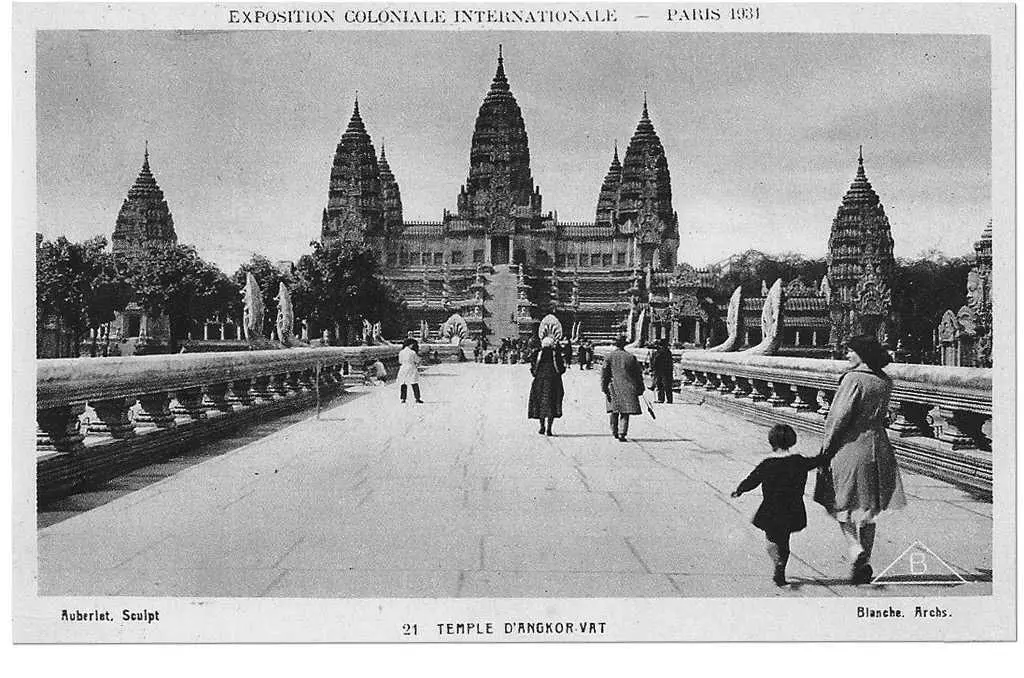

In 1931, Jean-Baptiste helped design the Indochina Pavilion at the Colonial Exposition in the Bois de Vincennes. A reconstruction of Angkor Wat’s central tower complex was built next to a Laotian fishing village and an exact copy of La Seule Vérité’s rubber-processing hall, where the latex was squeezed into sheets and then hung to dry. Jean-Baptiste oversaw its re-creation. Forty full-grown hevea trees were shipped in from Brazil and planted in their orderly rows. At first they would not bleed, so a mixture of goat’s milk fortified with flour was concocted to mimic the appearance of fresh latex.7

Fig. 4.3. Pavillon de l’Indochine à L’Exposition Coloniale Internationale de 1931, Bois de Vincennes, Paris

From Tofte-Jebsen, B., Jeg er Raksmey, p. 98

The organizers of the exhibition asked Jean-Baptiste to give several on-site lectures about the biological wonders of Southeast Asia, and it was during one of these lectures, which was halted prematurely by a rare tropical downpour, that he sought shelter beneath the Angkor Wat simulacrum with a pretty woman who shyly introduced herself as Leila Cousaine. She was from Normandy. She was in town with her parents for their annual shopping excursion, and a friend had told her about the wonders of the exposition, which she had decided to reconnoiter for herself. She admitted her admiration for his talk and said she had always dreamed of traveling the world but lacked the valor and constitution to do so. Jean-Baptiste noticed immediately that the color of her eyes did not match — her left was a luminous shade of aquamarine and her right was a reddish flint tone that had a way of catching the light at certain angles. He wanted to ask her about this particularity but instead made a hasty and embarrassed dinner invitation for the following evening, which she accepted on the condition that her father gave his consent.

They dined at an art deco brasserie in Montparnasse. The meal was halting and awkward — Jean-Baptiste oscillated between lecturing her on plant species and asking questions that came off as impertinent. After a while, he fell into a kind of half silence marked by inappropriate humming. Leila, clearly intimidated by her partner, spent most of the meal with eyes downcast, answering his queries without enthusiasm. Toward the end, as they waited for a pair of crèmes brûlées that couldn’t come fast enough, Jean-Baptiste, thinking nothing could make the evening go worse, mustered up the nerve to ask her his original question, albeit without asking a question at all.

“Your eyes,” he said.

“My eyes?” she said, glancing up at him, briefly revealing the pair of mismatched wonders before maneuvering her gaze once again to the hem of the tablecloth.

“They are. .” He drifted. “I’ve never seen them before.”

“Of course you haven’t seen them before. We’ve never met before yesterday, Monsieur de Broglie.”

“Yes,” he said, embarrassed. “I suppose we haven’t. But your eyes are different. That is, they are different from each other.”

“My mother says they make me look wolfish.”

“Wolfish? Heavens, no. They’re beautiful,” he said. “Truly. I could live a thousand years and never see something so beautiful.”

She blushed and flashed him a cautious smile, her first true smile of the evening.

“The Cambodians believe the eyes never change,” he said. “You can go through an infinite number of reincarnations, but your eyes will always remain the same. It’s how we recognize our friends and enemies across time. So perhaps you came from two different people. Or one person and one wolf.”

She laughed, miming a snarl and raising a mock paw. The moment vanished just as quickly as it had appeared.

“Will you ever go back?” she asked, recovering. “Back to Indochina, I mean.”

“Of course,” he said, still staring at her lips. “It’s my home. My father and mother are still there. They expect me to come back.”

“Yes, but how do you know it’s your home? You seem so at ease here.”

“I feel at ease here.”

“Then your home is where you were born?”

He shook his head. “Your home is where you will be buried.”

“That’s a little morbid, isn’t it? I mean, for me, a home is where I shall want to live.”

He straightened his napkin. “Forgive me.”

“For what?”

“I’m not used to a lady’s company. I grew up under isolated circumstances. You must have thought me a worldly gentleman, only to be sorely disappointed when you met the insensitive impostor before you.”

“On the contrary,” she said. “But then you must find me so boring. ‘Une petite nonne normande,’ as my sister says.”

“Not at all,” he said quickly. “It’s not every day that you meet a wolf.”

That night — in the transience of that snarl, in the delicate collision of their words — a mutual acknowledgment of need was established. Not quite love, but something more useful, which would eventually grow into a kind of interdependence. On paper, such a thing was not all that different from love.

Leila came to tolerate Jean-Baptiste’s habit of leaving a conversation in midsentence to examine leaf structure and, as it turned out, such tolerance was just enough. They were married in 1933, in the gardens of the Muséum National d’Histoire Naturelle, in front of her family and a small collection of scientists and acquaintances from the colonies. Eugenia and André elected not to make the trip.8

During those fleeting years in Paris, as fascism began to rear its ugly head to the east, Jean-Baptiste lived a charmed life of fitful ideas. He started and did not finish a thesis on Heidegger ( Dasein, Terreur, et le Regret du Colonialisme ) and then started and did not finish a thesis on epiphytic orchid propagation. Everything was captivating from a distance, but as soon as he got too close to a topic, his interest began to wane. He enjoyed dropping in at the laboratories of the Polytechnique and listening to lectures on physics and astronomy by the visiting scholars, because most of what they said he could only marginally understand, and this kept him hungry.

One of these lectures was given in the dead of winter by Georges Lemaître, a bespectacled, portly priest from Belgium who was the first person to propose that the universe was expanding, much to the twin annoyance of the Catholics and Einstein, who both claimed that Lemaître was meddling in territory beyond his comprehension.

Monseigneur Lemaître’s talk at the Polytechnique was on how one might go about calculating the precise age of the universe, an act he did not see as being at odds with his faith. As he put it: “Even God enjoys a birthday party. One common mistake is to attempt to solve scientific problems with religion and religious problems with science. Each must be solved in the state in which it arises.”

Читать дальше