“Nearly anything can be cultivated anywhere, given the right care and attention,” Henri said to his bemused guests. “Certain environments demand more care and attention, but this is not a failure of the cultivar. Any failure lies squarely on the shoulders of the cultivateur .”

Then he would take them through the young hevea grove. The trees were planted at precise distances such that no matter where one stood, the rows would form and re-form into an infinite kind of order. There was no way to unbind them.

Koko bore Henri a son, André, who, despite his Khmer lineage, looked very much like a round-faced Frenchman left out in the sun to ripen, a true Indochine français.

Henri would not live to see his grand vision come to fruition. On December 31, 1899, five minutes before the dawn of the new century, he succumbed to a swift and brutal case of hemorrhagic dengue fever. The servants, unsure of what to do, lit off the fireworks anyway. The explosions flushed open the night, momentarily revealing the great jungles beyond before their dying embers streamed down into the cool, black river, where they hissed and sizzled into silence.

On New Year’s Day, as word of Henri’s death spread up and down the river, more news came to join it: Koko had disappeared during the night, taking with her a box full of jewelry and several thousand francs. Despite some efforts by colonial forces to locate her, she would never be seen or heard of again. There were rumors, of course: that she had fled to Paris and had opened a successful Indochine-themed lounge and nightclub; that she had been murdered for her jewels by a group of masked men near the Laotian border. One story even claimed she had used witchcraft to assume the appearance of a white man and now ran a nearby plantation.

“The only way you can still tell who she once was,” said one of the characters in Tofte-Jebsen’s novella, “is to catch her sleeping and shine a torch into her eyes. A person can never change their eyes when they dream” (56).

André de Broglie, barely nineteen years old and now an orphan, was left to manage the plantation on his own. Luckily, his hand was steady, and the fledgling century would witness the swift rise of an automobile driven on the rubber pneumatic tire. Seemingly overnight, the global demand for latex exploded. La Seule Vérité—primed by Henri’s hubris for just such an explosion — eventually grew to thirty thousand hectares, with a workforce of more than six hundred indentured Vietnamese laborers.

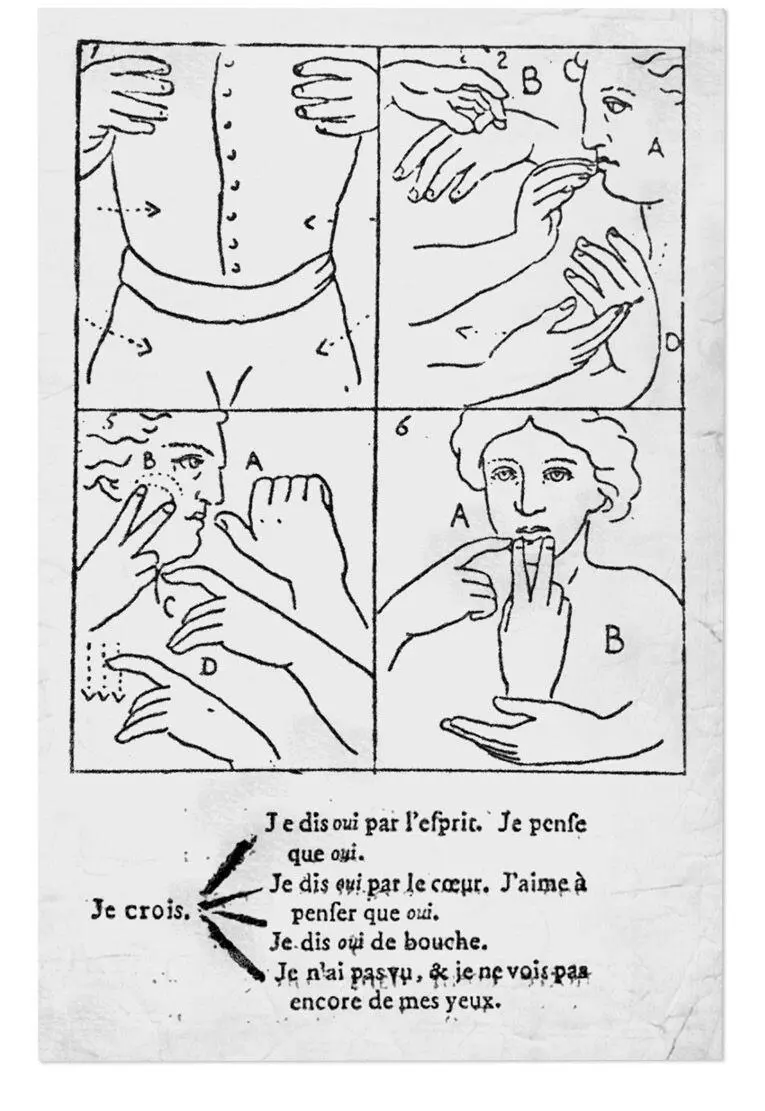

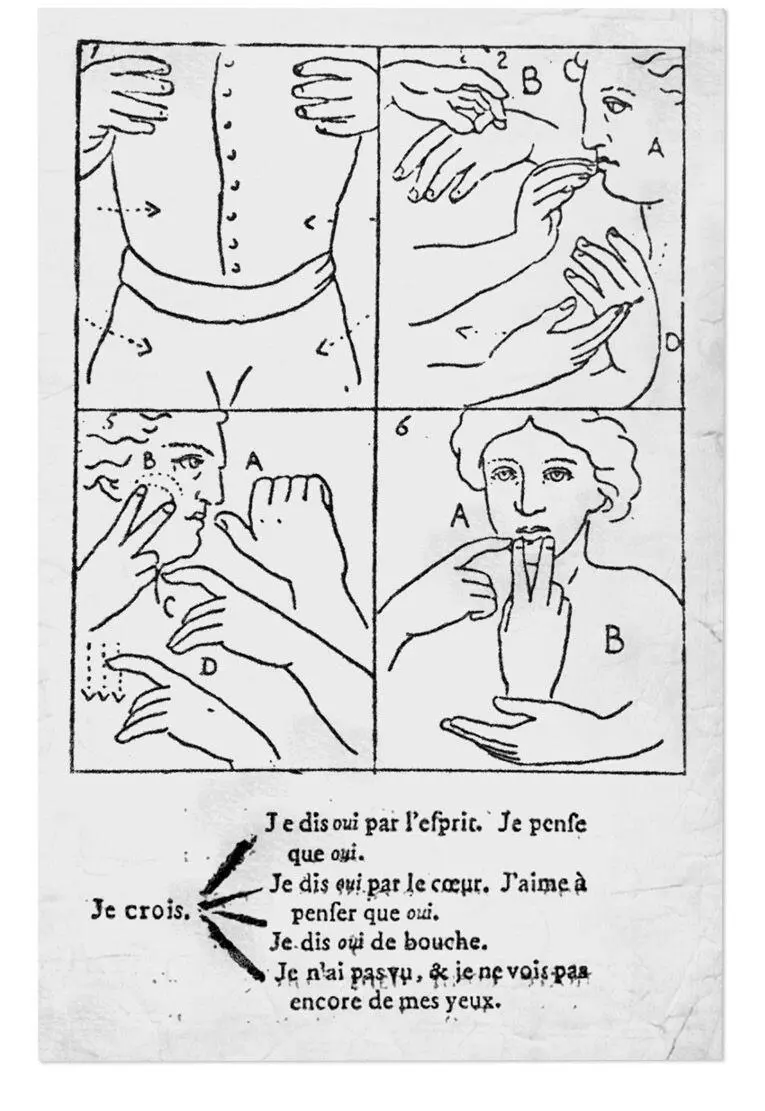

When he was twenty-four, André floated down to Saigon and returned with a wife standing upon his prow. Eugenia was the eldest child of Pierre Cazeau, the stately, arrogant owner of the Hôtel Continental, on rue Catinat. She was also deaf. Her tutors had spent the first thirteen years of her life attempting to teach her how to speak like a hearing person, as was dictated by the popular pedagogy of the time. Her tongue was pressed, her cheeks prodded, countless odd intonations were coaxed forth from her lips. Cumbersome hearing horns were thrust into her ears, spiraling upward like ibex horns. It was a torture she finally rejected for the revolutionary freedom of sign, which she taught herself from an eighteenth-century dictionary by Charles-Michel de l’Épée that she had stumbled upon accidentally on the shelf of a Saigon barbershop.5 Based on the grammatical rules of spoken language, L’Épée’s Methodical Sign System was unwieldy and overly complex: many words, instead of having a sign on their own, were composed of a combination of signs. “Satisfy” was formed by joining the signs for “make” and “enough.” “Intelligence” was formed by pairing “read” with “inside.” And “to believe” was made by combining “feel,” “know,” “say,” “not see,” plus another sign to denote its verbiage. Though his intentions may have been noble, L’Epée’s system was inoperable in reality, and so Eugenia modified and shortened the language. In her hands, “belief” was simplified into “feel no see.” Verbs, nouns, and possession were implied by context.

Fig. 4.2. L’Épée’s Methodical Sign System

From de l’Épée, C.-M. (1776), Institution des sourds et muets: par la voie des signes méthodiques, as cited in Tofte-Jebsen, B., Jeg er Raksmey, p. 61

One could not quite call her beautiful, but the enforced oral purgatory of her youth had left her with an understanding of life’s inherent inclination to punish those who least deserve it. Her black humor in the face of great pain perfectly balanced her new husband’s workmanlike nature. She had jumped at the opportunity to abandon the Saigon society that had silently humiliated her, gladly accepting the trials of life on a backwater, albeit thriving, plantation. Her family’s resistance to sending their eldest child into the great unknowable cauldron of the jungle was only halfhearted — they were in fact grateful to be unburdened of the obstacle that had kept them from marrying off their two youngest (and much more desirable) daughters.

André painstakingly mastered Eugenia’s language. Together, they communed via a fluttering dance of fingertips to palms, and their dinners on the veranda were thus rich, wordless affairs, confluences of gestures beneath the ceiling fan, the silence broken only by the clink of a soup spoon, the rustle of a servant clearing the table, or the occasional shapeless moan that accentuated certain of her sentences, a relic from her years of being forced to speak aloud.

Eugenia began to paint. She painted the rows and rows of rubber trees. She painted the bougainvillea. By torchlight, she painted the flowers of the Epiphyllum oxypetalum cactus that bloomed only once a year, and only at midnight. Her paintings were better than they should have been, primarily because of her unusual color palette: nothing appeared as it should. Colors were reversed, dulled, heightened. Eugenia claimed that this was how a blind person would see the world if he or she were to suddenly gain sight.

André had inherited the de Broglie curse of recording everything possible. In the vault next to his father’s giant sheepskin books, he began to accrue his own ledgers. Unlike his father’s records, André’s notes were organized, fastidious, and — perhaps most important— legible . Yet even his rigorous accounting did not always tell the full story, either. For instance, when he wrote, “1906 — 8 personnes contractent la syphilis,” he did not recount that one of these eight cases was actually himself, and that the source of the outbreak was a prostitute who had arrived from Phnom Penh under the guise of being one of the worker’s sisters attempting to escape a battered marriage. The prostitute then proceeded to purvey her services for a month before she was found drowned in the Mekong, her mouth stuffed full of stones. Her death was dutifully noted in the tally for that year without comment: “mortalité totale — 26 (1 de vieillesse, 5 du paludisme, 2 de la dengue, 4 d’une maladie cardiaque, 7 d’une pneumonie, 3 de la tuberculose, 3 de causes inconnues, 1 par noyade).” Flip forward a few pages and you will find the total profit for this year as well: “1,931,398 FF”— an astounding amount, considering time, place, and circumstance.

As their fortune grew, André remained keenly aware that he was reaping the delayed fruits of his father’s persistence, that nearly every one of his triumphs was not the result of his own doing but rather a by-product of his predecessor’s brilliance. Yet instead of neutering his sense of achievement, such knowledge exonerated him from ever having to find his own way. His destiny had set him free. Henri’s gravestone, which André paid a visit to every Sunday, presided over the plantation from a hilltop. Its inscription, a phrase of the Buddha’s that a local boatman had reportedly recounted for Henri, read thus:

Читать дальше