He took another drag from the cigarette, slowly, longingly, a breeze bending a twig, and then he heard a noise coming from the ditch behind him, a sound like the hushed whistle of a teakettle left to simmer on a stove. Tien ran the back of his thumb against his lip and shook the ash from the tip of his cigarette. He did not move. It was too hot to move, too hot for anything except that which was absolutely necessary. In heat like this, you had to decide your actions long in advance.

The sound came again, insistent, louder this time. Tien closed his eyes, the image of a woman coming into his mind: a torso, naked and white in the light, a shawl of saffron dragged across the thin curve of her shoulders. The woman turned her face toward him, and that elemental ache returned, but then the vision evaporated as the sound came a third time, now forming into a cry that could only have arisen from the lungs of a human. Tien exhaled, carefully stubbed out his cigarette, and placed it into an overflowing tin can, the label peeled clean. He got down on all fours and peeked over the edge of the ditch, afraid of what he might see.

What he saw stunned him: a naked baby, floating in the scoop basket of a conical sedge hat. The child, exposed to the heat of the sun, was shriveled, a deathly pale yellow-green, the size and color of a pomelo fruit. Too tiny to be alive. But it was alive: now it was moving an arm and again making that strange whistling sound.

“Come,” Tien called to the others. “Come. Come quickly. Look what I’ve found.”

The others looked, blinking in wonder. It was agreed: this was the smallest baby they had ever seen. It was agreed: the child would not survive.

Tien fished the hat from the water and wrapped the baby in his red checkered scarf.

“Go get Suong. She can give him some milk,” he said to Keo.

As they waited, there was much debate among the men. What to do? Was it a test? A trap? The baby looked Cambodian, perhaps Laotian, and the first thought was that it must’ve been one of the workers on the plantation who had delivered the baby and then abandoned him. This theory was passed around and digested and eventually rejected. None of the women workers had been far enough along to deliver even a baby as tiny as this.

Suong arrived at the ditch, the sweat catching in the crinkles of her eyes. It was much too hot for a child to be in the sun. She took him to the shade of the banana tree, where she coddled the child, pinching at the diphthonged knees, the miraculous little legs, no bigger than her fingers. The child’s coloring was all wrong — he was suffering from disease. She lifted him to her breast, humming a wordless song, but he would not take the nipple.

“He’s sick,” she said. “He’s too small to drink. He will die.” Her tense shifted. “He’s dead.”

• • •

AT LEAST this was the version of events described in Brusa Tofte-Jebsen’s obscure novella Jeg er Raksmey (Neset Forlag, 1979), which utilizes the usual mixture of pictures, diagrams, and prose that was so popular in Scandinavian literature at the time. Yet Jeg er Raksmey was also another sad example of a book written but hardly read; it sold barely half of its listed first run of 750 copies before the rest were sent to the pulper in Lysaker. The slim book did have one notable (if not surprising) reader: Per Røed-Larsen. In a section of Spesielle Partikler entitled “En elementær partikkel er en partikkel som ikke kan brytes ned til mindre partikler” (“An elementary particle is a particle that cannot be broken into smaller particles”), Røed-Larsen devotes a mind-boggling amount of time and space refuting the factual basis of Tofte-Jebsen’s story, despite Tofte-Jebsen’s making no claim that his book is anything but fiction. Røed-Larsen disagrees. “[ Jeg er Raksmey ] is near-truth posed as fiction and I can think of no worse crime,” he writes. “It has thus become my beholden duty. . to set the record straight. We must stick with the facts and only the facts” (591).

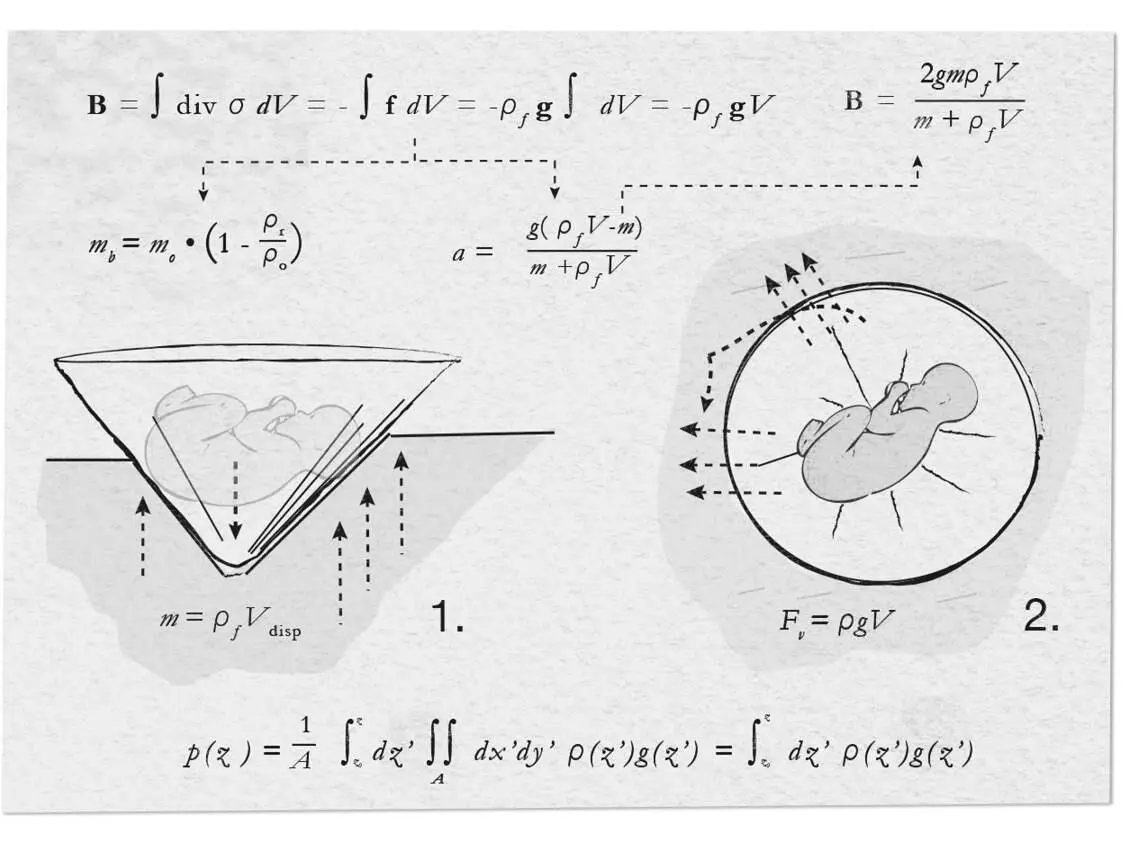

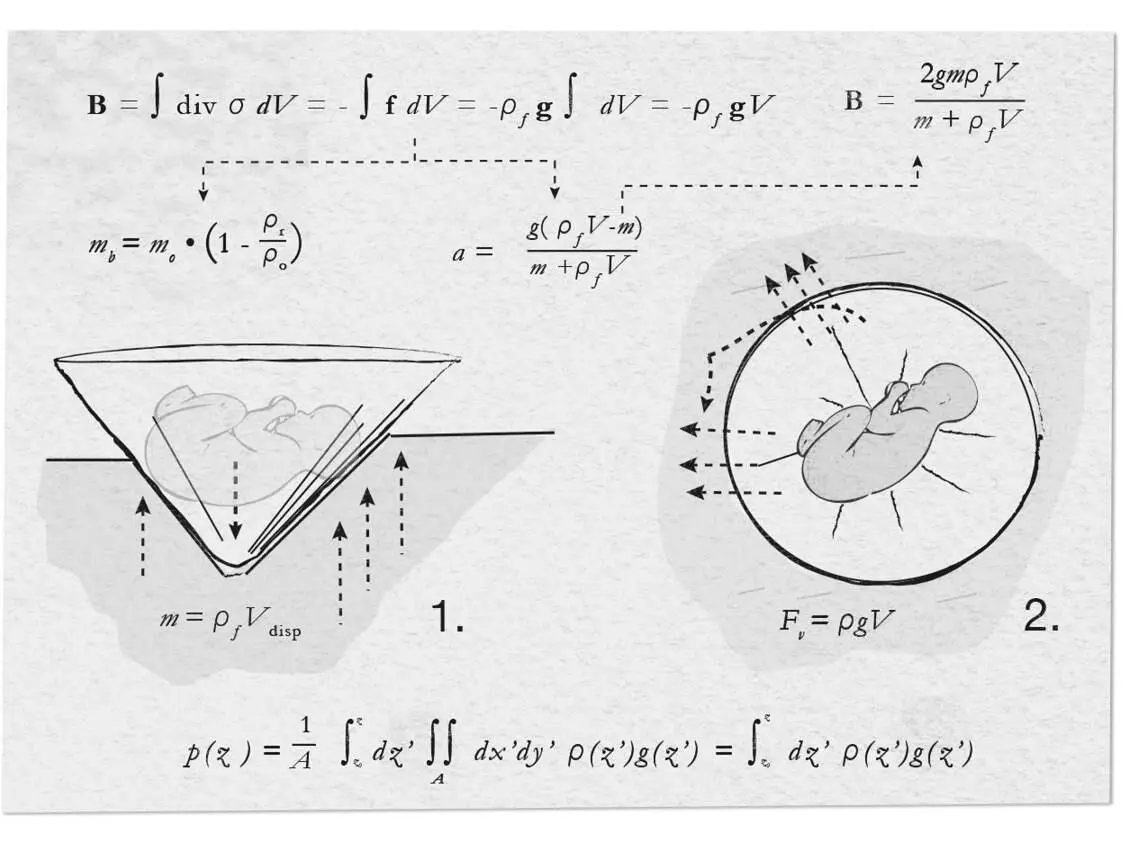

In particular, Røed-Larsen is bothered by Tofte-Jebsen’s claim that the child was discovered in a floating hat. In building up a case against such an origin story, Røed-Larsen references (among other things) the improbable buoyancy quotient of a newborn’s (even an unusually small newborn’s) staying afloat inside the leaky and unstable containment vessel of a palm-leaf nón lá hat (591–93). Much more likely, Røed-Larsen argues, was that the child was given directly to Tien by one of the women on the plantation, sans floating hat.

No matter. Regardless of how he was discovered, what cannot be disputed is that the child had chosen a most unusual landing point for his entrance onto the stage. Owned by the de Broglie family for three generations, La Seule Vérité was one of the few French rubber plantations still operating along the banks of the Mekong. In 1953, France was already seven years deep into its dirty war with the Viet Minh, unable to relinquish its Indochine colonies without a protracted, bloody fight that would culminate the following spring on the slopes of Dien Bien Phu. La Seule Vérité, perched on an oblong bend in the river, was both of this empire and wholly separate from it, a place that had gracefully excused itself from the normal laws of both space and time.

Fig. 4.1. Nón lá Hydrostatic Buoyancy Analysis

From Røed-Larsen, P., Spesielle Partikler, p. 592

After some discussion, the workers decided to present the baby-who-was-dead-but-not-dead-yet to the manager of the plantation, Capitaine Claude Renoit. Capitaine Renoit had lost a leg early in the war and had come to La Seule Vérité to sulk and wax on about the decline of everything that once was great about the land. But he was an honest man, and he treated the workers as well as they could hope for. He did not believe in an excess of suffering, and so he would know what to do with the child. If he gave permission for the little thing to die, then the child’s spirit would not blame them when it found no place to rest.

Renoit was sitting on the patio, thumbing at a glass of Courvoisier, the ledger sheets splayed out before him. A fleeing diplomat had given him the bottle in Saigon for services rendered on the battlefield, and Renoit had been saving the cognac for a special occasion ever since, but it was becoming more and more likely that he would die before a worthy occasion came, so he had broken the seal and let the old liquid cut through the heat of his body. These grapes were from Napoleon’s time, when empires were carved with simple gestures of the hand. Renoit found himself wondering whether, if the worst were to happen, he would kill himself or let another man have the pleasure. He had seen enough to know that in every death, someone suffered and someone triumphed, and often those two were the same person.

He was startled out of his reverie by a group of coolies coming up the hill from the rubber fields. Someone must have died again. This was both annoying and somehow exhilarating.

We’re still making the rubber. We’re still dying to make the rubber. It didn’t matter what the ledger sheets said. La mort est notre mission civilisatrice, Renoit thought, and took a sip of the cognac.

When presented with the baby, Renoit, like all the others, was taken with the child’s almost mystical diminutiveness. Its fingers like tiny spiders, toes like grains of rice.

“What the hell do you want me to do?” Renoit said to Tien, who was offering the child with outstretched arms, like a gift. “He’s one of yours. Fais-en ce que tu veux .”

Читать дальше