Fig. 4.11. Tuol Sleng prisoner #4816

From Røed-Larsen, P., Spesielle Partikler, p. 658

Of the seventeen thousand prisoners who passed through Tuol Sleng, only seven survived. Nhem En’s black-and-white photographs of the prisoners remained in a file cabinet in the school’s old cafeteria after the Khmer Rouge fled the city, though at some point the photographs became separated from their files, so many of the images live on in a liminal, unidentified state. A man resembling Tien is pictured among these photographs, #4816, although, without proper documentation, one cannot be sure if it is actually him or someone else entirely:

Yet even just this act of immortalizing a prisoner in a photo, filled with its soft palette of greys and marked by the subject’s vacant stare of simultaneous comprehension and disbelief, was more attention than the vast majority of the regime’s victims received. Most were never documented by their killers. They slipped into death anonymously, silently, leaving no proof of their existence or of their abrupt demise.

It is here that Røed-Larsen (and by extension we ) enter the realm of conjecture. Following the “liberation” of Phnom Penh, Raksmey was able to disguise himself as a peasant and evade execution, presumably because he was mostly unknown to the population. After walking out of the city with the rest of its inhabitants, he was sent to work up north in the rice fields in the Preah Vihear region, near Tbaeng Meanchey district. He survived only by completely abandoning his identity and pretending he was deaf and mute — for more than two years, he did not speak. It must be said, his deafness was a dangerous choice, for those with disabilities were also culled. Raksmey, however, compensated for this with tireless work in the fields, and thus ingratiated himself with the Khmer Rouge district leaders, who were less ruthless than in other sectors. As Røed-Larsen writes, “Cruelty is always local. . [it] depends not upon the system which creates it but the hand that serves it” (660).

In the evenings, Raksmey would smile and clap as his exhausted comrades chanted songs pledging their allegiance to Angkar. When the Khmer Rouge cadres gave lectures on the triumphs of the Kampuchea state, Raksmey made sure his head was downcast, his eyes dull and empty, so that the chiefs would not detect any hint of life or understanding in them. He thus lived two lives: a life inside the crevices of his mind, where he unwound particles and debated the theories of subatomic quantum mechanics late into the night with an apparition of Dr. Salam, and another that comprised his outward actions during the day, where he was deaf and mute. A simpleton. Eager to please, eager to serve the great and powerful Angkar. Even in the darkest hours of the night, he made sure that his two lives never crossed paths, never greeted each other.

“Angkar!” he would yell with the others in a mangled voice of incomprehension. It was the only word he allowed to pass his lips — two declaratory vowels draped in vague consonants. It was not so much a word as a breath and release: “Ang- kar ! Ang- kar !”

During the monsoon season of 1977, he and two others managed to escape their work camp by foot, over the Dângrêk Mountains and into Thailand. One of the men died en route after stepping on a land mine, and the other succumbed to illness as soon as he reached the safety of Thailand.

In Bangkok, Raksmey took up a research assistantship in the physics department of Chulalongkorn University for Dr. Randall Horwich, the friend of a colleague at CERN. Dr. Horwich must have been surprised at who had crawled into his lab from Democratic Kampuchea, which at the time remained an impenetrable mystery to the world. It was a fortuitous arrival that would help to jump-start Dr. Horwich’s career. Together, they co-published an important theoretical paper in 1979 on the mass of up quarks in the Pakistan Journal of Pure and Applied Physics. This paper precipitated Dr. Horwich’s move to CERN in 1980, where he would work on the UA1 experiment, which definitively discovered W and Z bosons and won its research heads a Nobel Prize.

If nothing else, Raksmey’s reentrance into the world of record keeping did yield valuable evidence of his survival: along with the theoretical paper, Per Røed-Larsen managed to track down his letter of hire at Chulalongkorn, several pay stubs, and a university work transcript. There is also one improbable document that stands out from the rest: a handwritten letter, purportedly written by Raksmey to his friend Sebastian Ouellette, a fellow researcher at CERN.

The letter is dated April 18, 1975:

My dear Sebastian,

The Khmer Rouge have finally arrived in Phnom Penh. Yesterday everyone was very glad to see them, people were clapping and cheering in the streets. Many think this is the end of the war though I fear for the worst. . I tried to speak with one of the soldiers but he only screamed at me to back away. His eyes were dead. When I saw this, I knew very bad things are ahead. These soldiers have not been trained to run a country. They are trained to kill. Maybe I’m wrong about this. I hope. I hope.

I’m mailing you this letter on the off chance it will get out of Cambodia. Most probably it will never arrive. I miss you and our laboratory in the fields. It feels so incredibly far away right now. What a privilege it is to work there. If anything happens know that I will never forget you.

Fondly,

Raksmey de Broglie

P.S. I had the strangest dream last night. It was very vivid. I was on a river, lying in a boat. I’m not sure what river. It wasn’t the Mekong. But then suddenly I felt as if I was no longer alone. I felt another person was with me — there was no one else on the boat but I felt whole, as if I had found my other half. When I woke up this morning I was still filled with this feeling of completion. I wonder what it means? Maybe I am just suffering from nerves.

Miraculously, this letter survived, according to Røed-Larsen, although it was delayed somewhere along the way and was not delivered to CERN until five years later.

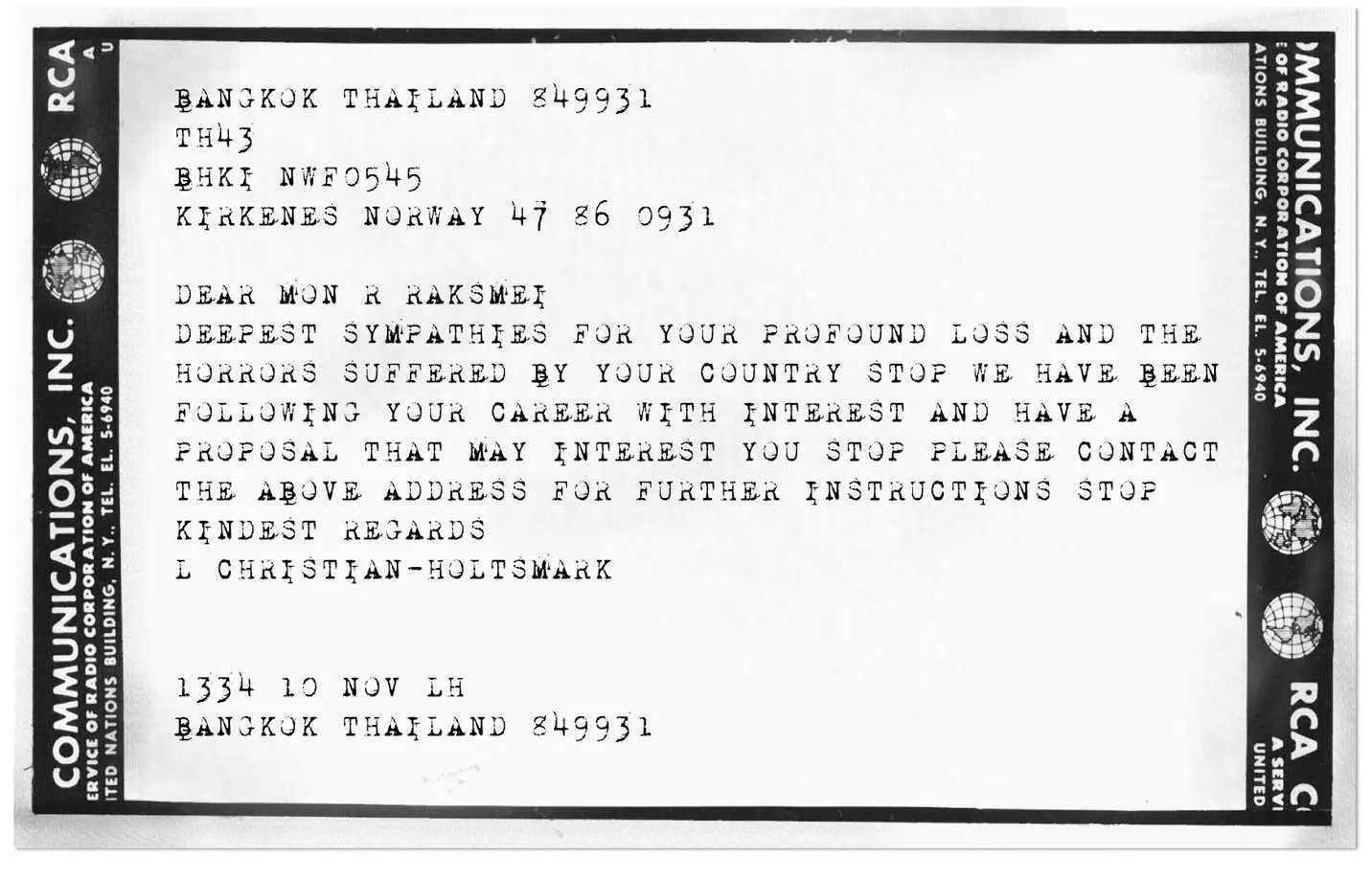

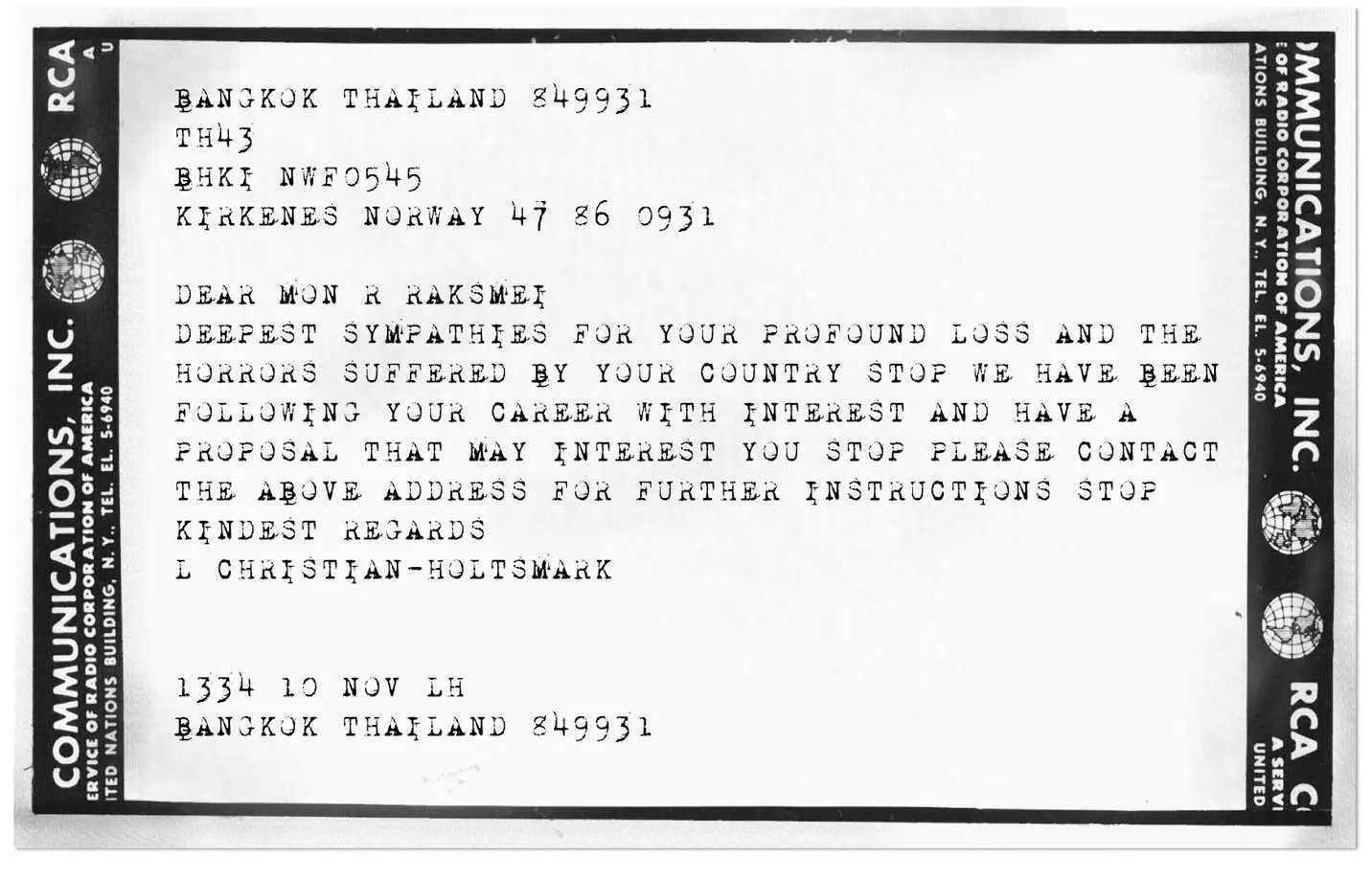

Per Røed-Larsen also includes a telegram sent to Raksmey while he was staying in Bangkok. The telegram was sent from Kirkenes and received on November 10, 1979:

Fig. 4.12. The initial telegram, November 10, 1979. The only surviving piece of communication between Raksmey and Kirkenesferda.

From Røed-Larsen, P., Spesielle Partikler, p. 670

After some negotiation, including several telephone calls, Dr. Christian-Holtsmark gradually made clear to Raksmey the extent of his request. Raksmey was to help negotiate their passage to the highly secretive “Camp 808,” just north of Anlong Veng on the Thai border, where the Khmer Rouge had retreated to a jungle base following the Vietnamese invasion. It is unclear how much Raksmey came to understand, over the course of these transmissions, the extent of Kirkenesferda’s ideology or motives, or what they planned to do once they had entered the camp. These telephone calls were not recorded, nor did Raksmey keep any journal or notebook, so Røed-Larsen is left to speculate why, given his horrific experience at the hands of the Khmer Rouge regime, he would have agreed to place himself so dramatically in harm’s way on behalf of an unknown group. Røed-Larsen is quick to stress that, once onboard, Raksmey was not merely a hired gun, as Kirkenesferda did not believe in mercenary fixers. Writes Røed-Larsen, “From the minute they landed, [he] was accepted into the group, full stop, as an equal player. . Kirkenesferda’s eighth official member” (675).

Читать дальше