He then, it is said, walked out in the middle of the lecture.

Regardless of Tofte-Jebsen’s motives, if we are to discover anything more about Raksmey’s story, we must turn exclusively to Røed-Larsen’s account in Spesielle Partikler . Keep in mind that Røed-Larsen’s Raksmey is not Tofte-Jebsen’s Raksmey (and vice versa). We thus may sense a distinct break in character. To make matters worse, Røed-Larsen points to the nearly impossible challenge of establishing facts in post-independence Cambodia, renamed Democratic Kampuchea. After seizing power in April 1975, the Khmer Rouge regime famously declared that time had been reset to “Year Zero,” effectively wiping the slate clean of all Western influence, including historical written records.

Despite such formidable historiographical conditions, Røed-Larsen has done a remarkable job piecing together a crude timeline of Raksmey’s whereabouts from 1965 to 1979, which we may now summarize here.

In the mid-sixties, Raksmey spent three years at Collège Réne Descartes, in Saigon, under the personal tutelage of Rector Than; by all accounts, he excelled magnificently. When the American war in Vietnam began to accelerate, Rector Than had Raksmey graduate early, at age fifteen, while simultaneously convincing the admissions office at the École Polytechnique, in Paris, to admit him, despite his young age. Jean-Baptiste did not come to Saigon to see his son off. Instead, he sent him a letter, a copy of which apparently found its way into Per Røed-Larsen’s possession and was translated in Spesielle Partikler (640):

10 August 1968

Dearest Raksmey,

You must forgive me. I have not been well & am only now recovering from my illnesses. Please do not see my absence as having any reflection on my feelings towards your departure, which I regard with utmost excitement & pride. I have been getting updates from Rector Than about the rapid progress of your application. Your acceptance to the Polytechnique comes as no surprise, though I must admit it does bring me into a certain state of rumination.

You no doubt realized my great aspiration for you to become a physicist, an aspiration that guided the movement of my hand in nearly every choice I made while raising you. I recorded your progress in the volumes upon which I now gaze, volumes that seem lifeless without their subject. I now see this singular mind-set for what it is: a foolish defense which offered me shelter from myself. By sticking to my regime, I could deflect the fear I felt as my love for you grew. When we found you, you were so small, so sick, in the very borderlands of quietus. If only you could have seen the impossibility of your own existence! Your continued survival, against such odds, was extraordinary, & transformed us all — some for the better & some, like myself, I fear for the worse. My wife — whom in my head I still consider your mother — has never left me, & her legacy was alive & well when you floated by in your basket. My project was my way of rescuing you, but it was also my way of rescuing me.

Please, Raksmey, my dearest Raksmey, I beg for your forgiveness & I urge you, as you depart on the biggest journey of your life, to forget all that I have taught you & to listen only to the voice inside your own heart, if such a feat is still possible, given all the damage I have wrought. I am a selfish old man, a jealous, vindictive fool, who had no business doing what he did. Know that whatever path you choose, I will love you no less or no more. I am sorry for what I have inflicted upon you & no doubt what I will continue to inflict with the legacy of my actions. Nothing would make me so happy, or serve me so justly, as to see you decide to take up the profession of a cobbler, a mechanic, or a composer. Anything but the methods of science that I so bound you to.

Be well, my dear Raksmey, Raksmey. I have given you all & here I have nothing left to give.

With highest admiration,

your father,

Jean-Baptiste de Broglie

In the fall of 1968, Raksmey traveled to Paris to begin his studies at the École Polytechnique. He did not return home before this journey. Indeed, since that boat trip down the Mekong with his father and grandmother, Raksmey had not set foot in Cambodia.

Save his impeccable school transcript, not much is known about his time in Paris, about how young Raksmey navigated the trials of a large urban university in the late sixties, about whether he experimented with drugs, sex, or le rock and roll, or whether he simply stuck to his studies, as his prodigious academic record suggests. He took an average of eight classes per semester and graduated in four years, with a highly unusual dual master’s in quantum devices and applied particle physics. He also hosted a weekly classical music show on the university’s radio station, called La Vie Rallentando . What is most interesting is that Raksmey seemed intent on ignoring the advice of his father, which came either too late or too early. He would become Cambodia’s first (and only) particle physicist.

Accordingly, Raksmey promptly began work on a doctoral degree in quantum electrodynamics at the Polytechnique. He was offered, after some testy political negotiation within the department, a coveted fellowship at CERN, the international particle physics laboratory straddling the border between France and Switzerland. Only twenty-one at the time, Raksmey was the youngest doctoral student in CERN’s history. Under the mentorship of the theorist Dr. Abdus Salam and the experimentalist André Rousset, Raksmey wrote his dissertation, “On the Electroweak Interaction of Neutrinos with Quarks via Z Boson Exchange,” utilizing experimental research from CERN’s newly constructed Gargamelle bubble chamber. Several key points of Raksmey’s dissertation would later contribute to Dr. Salam’s winning the Nobel Prize in physics in 1979.

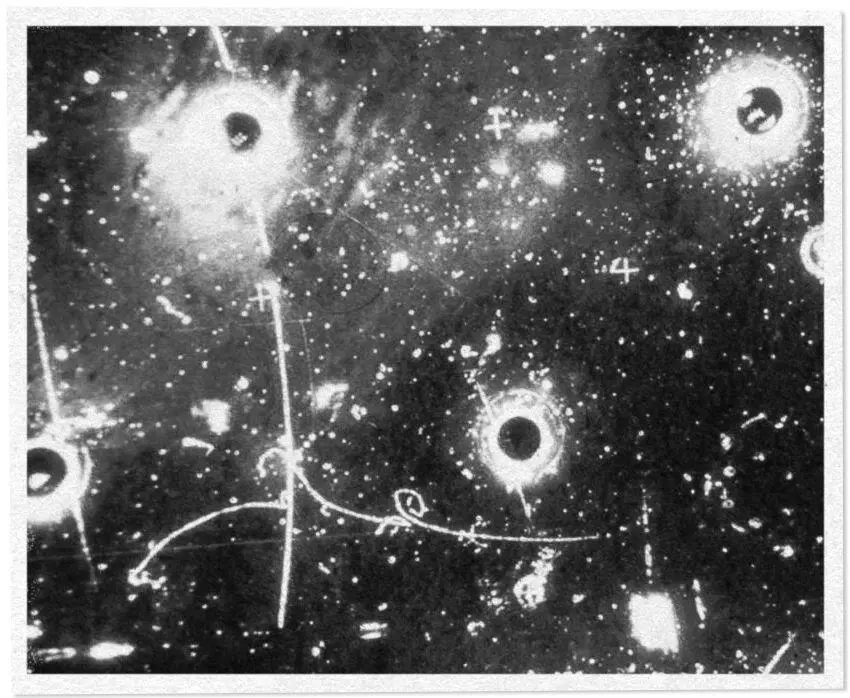

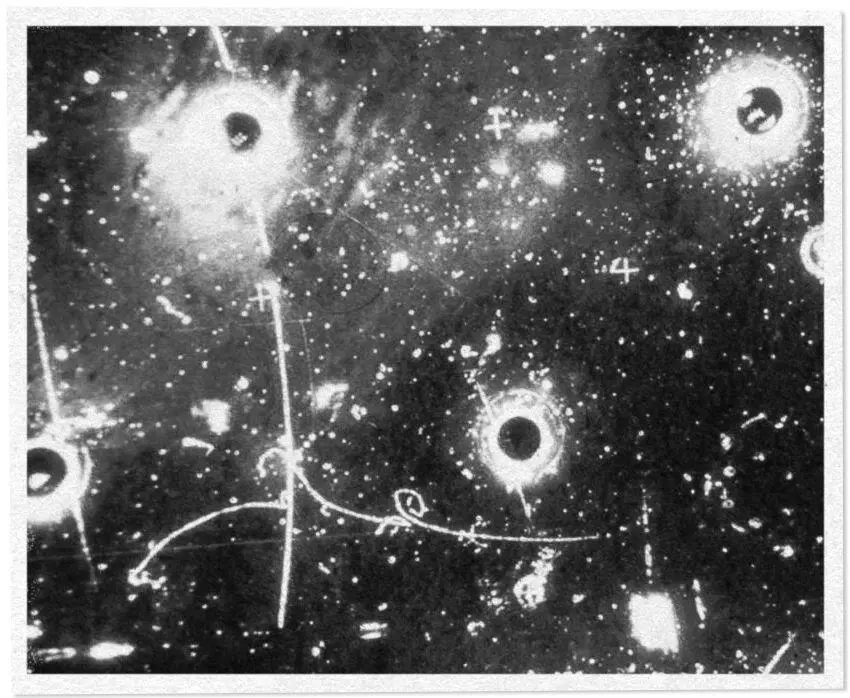

Fig. 4.8. “A neutral current event, as observed in the Gargamelle bubble chamber”

Image from R. Raksmey’s 1974 dissertation, “On the Electroweak Interaction of Neutrinos with Quarks via Z Boson Exchange,” as reproduced in Røed-Larsen, P., Spesielle Partikler, p. 651

Raksmey was quite clearly an eager and brilliant disciple of Salam, but he also struggled with social interaction. He had a small collection of English poetry in his apartment, as well as “several novels by Latin American authors” (653), including Julio Cortázar, and he enjoyed listening to Bach, Debussy, Shostakovich, and Britten. When not doing lab work, he often went hiking alone in the Swiss Alps.

In Spesielle Partikler, Røed-Larsen also cites rumors — although these remain unconfirmed — that Raksmey developed an intimate (possibly sexual) relationship with an older man, Dr. Alan Ferring, who was visiting the Gargamelle team from Berkeley, California. This relationship — if indeed it existed at all — must have been brief, for in September 1974 Ferring returned to his wife and family in California. Dr. Ferring apparently refused to be interviewed for Røed-Larsen’s book.

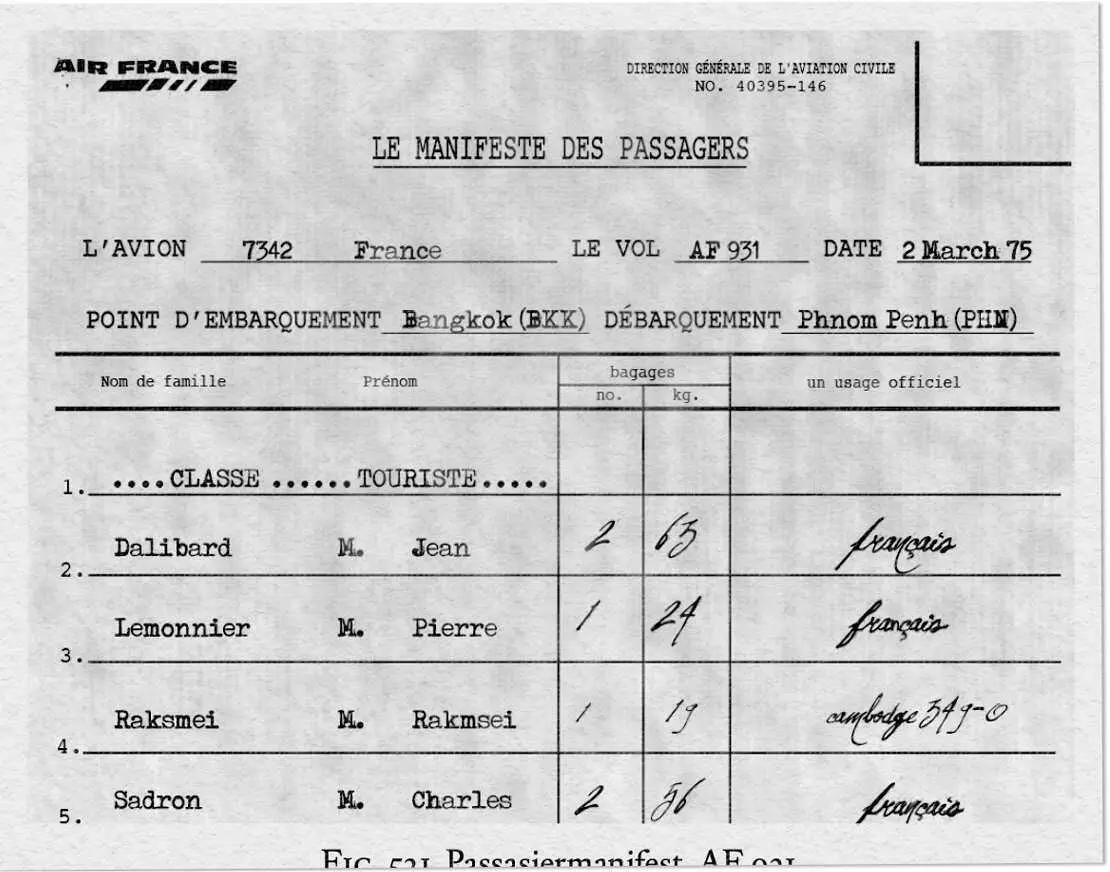

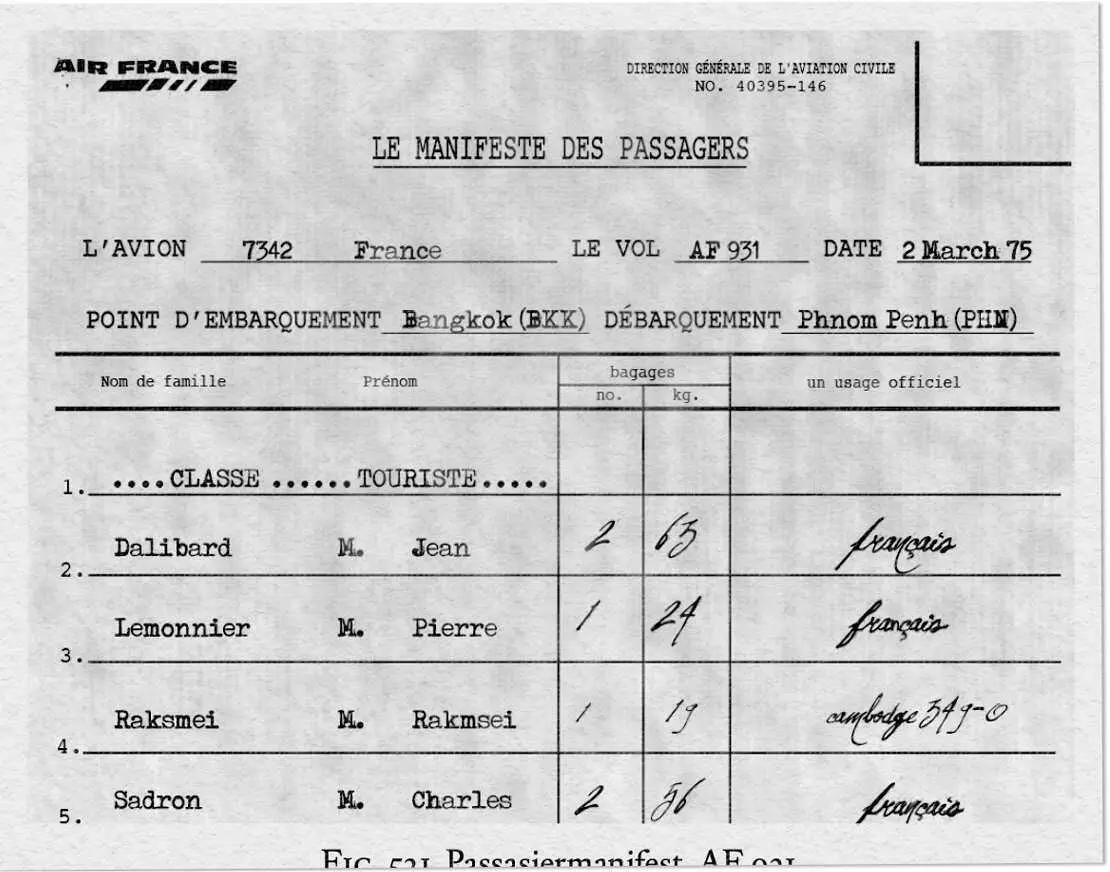

Fig. 4.9. Manifest from AF 931, Bangkok — Phnom Penh, March 2, 1975

From Røed-Larsen, P., Spesielle Partikler, p. 670

This much we do know: on March 2, 1975, Raksmey flew back to Cambodia after hearing news of his father’s death. Raksmey was listed in the passenger manifests of the Air France flights from Paris to Bangkok and from Bangkok to Phnom Penh — Flight 931, one of the last commercial flights to land in Cambodia.

Читать дальше