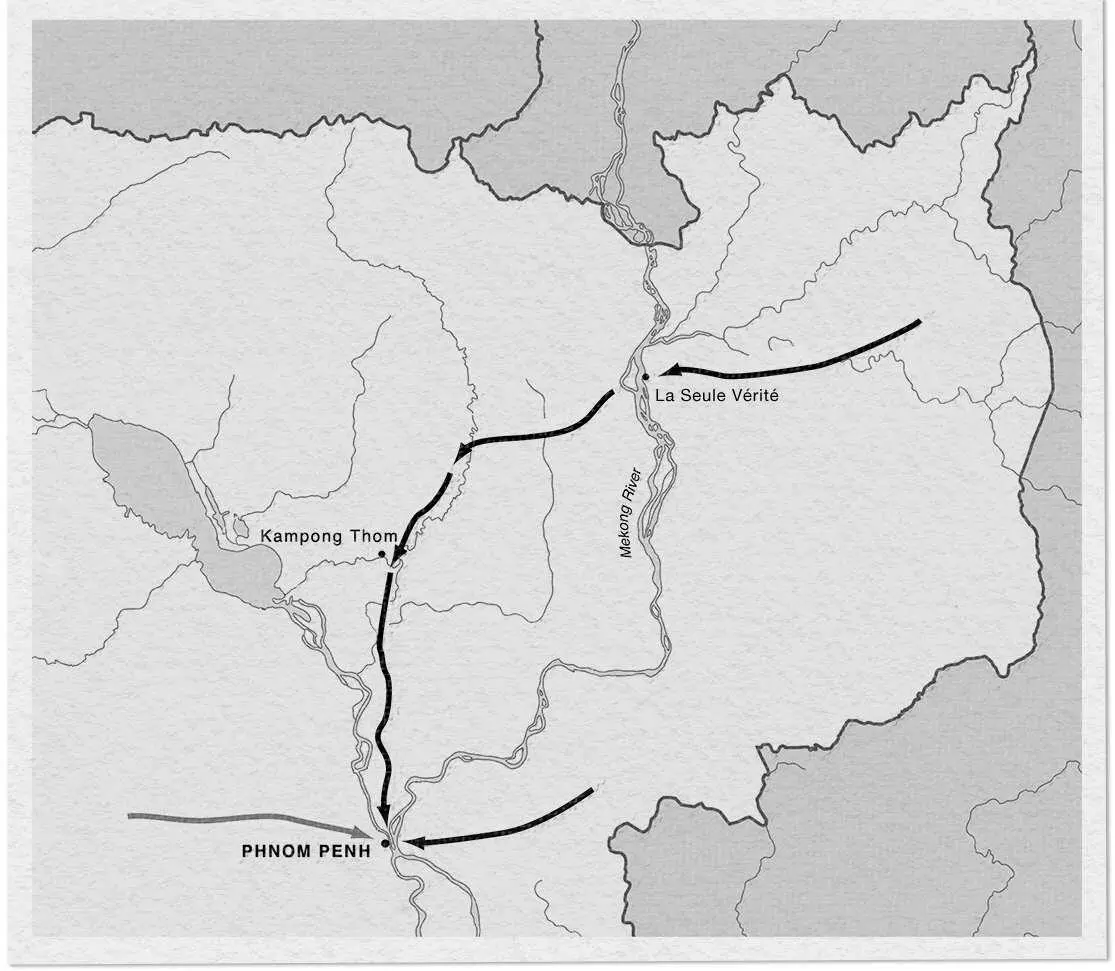

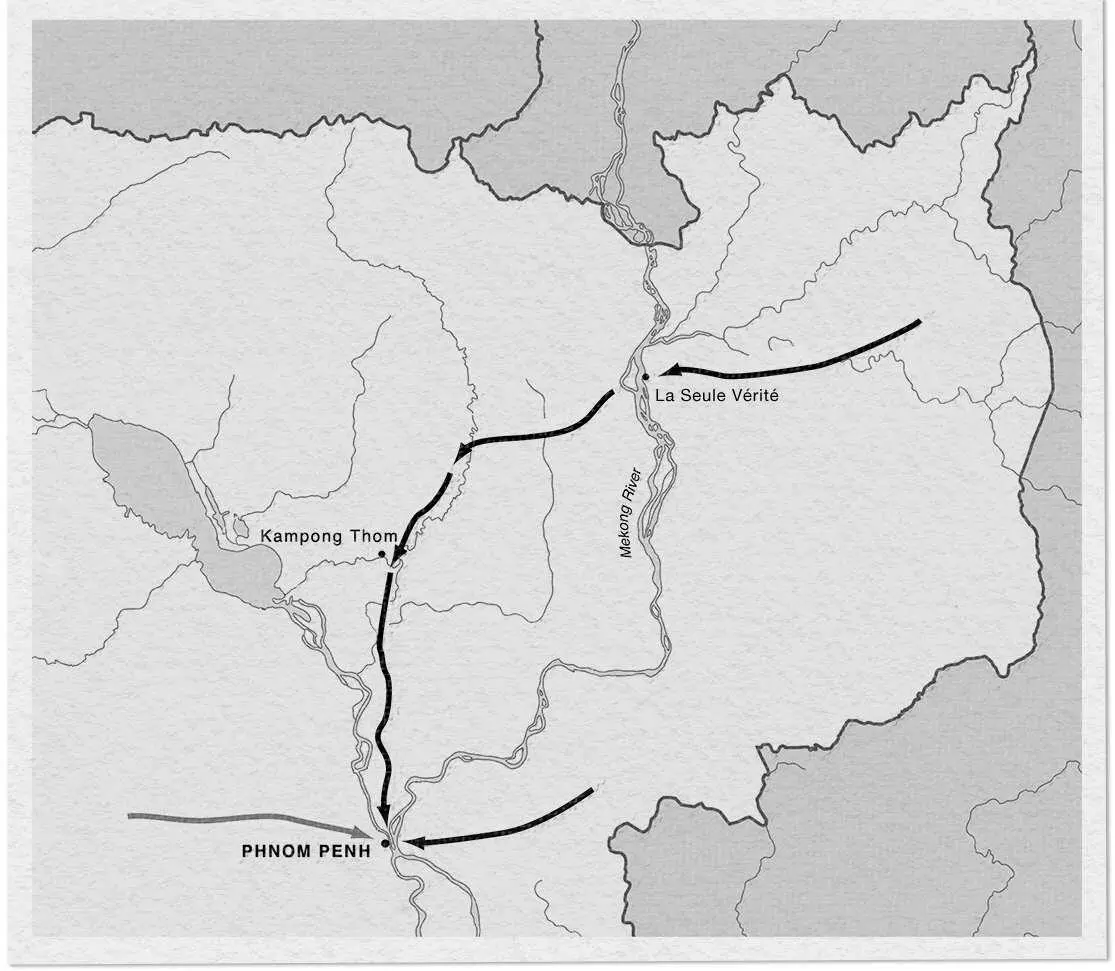

Regarding the circumstances of Jean-Baptiste’s death, Røed-Larsen, lacking much concrete evidence, contends that a small squad of Khmer Rouge troops, possibly heading southwest from their camp in Ratanakiri, near the Vietnam border, came upon La Seule Vérité by accident. Their movement was in the context of a larger dry-season mobilization of Khmer Rouge troops to Kampong Thom before a final push toward Phnom Penh down Highway 5.

According to Røed-Larsen, the encounter at La Seule Vérité was not without precedent. During the two years before, there had been plenty of fighting in the area between Khmer Rouge rebels and various divisions of Lon Nol’s woeful Khmer National Armed Forces. In 1973, an American B-52 had mistakenly dropped a payload of phosphorus bombs on the lycée, only three kilometers upriver, killing seventeen schoolchildren and the two missionaries from Texas. The school had burned for three days. Yet for the most part, La Seule Vérité had remained relatively unscathed by both the American war in Vietnam and the civil war raging in Cambodia. Rubber collection had completely ceased about five years earlier, following Capitaine Claude Renoit’s suicide, in 1969, and only a skeleton crew of five or six men remained with Jean-Baptiste at the time, maintaining the grounds, cooking, and ostensibly providing protection from hostile factions. On several occasions, representatives from the undermanned Cambodia National Army had recommended that Jean-Baptiste abandon his home and retreat to Phnom Penh, as they could no longer guarantee his safety. He had politely but firmly dismissed their counsel each time.

What happened on the night in question is not known. Tien managed to escape, but the plantation was burned, and it is unclear what was rescued from the fire. One can assume that all of Jean-Baptiste’s notebooks on Raksmey’s development — numbering perhaps 750—were destroyed, though less certain is the fate of André’s and Henri’s ledgers, which presumably remained locked in the basement safes. And what of Jean-Baptiste’s wager with himself concerning the fate of his only son, squirreled away in a rosewood box beneath the floorboards? Or the Reamker masks on the mantel? Or the strange wooden puppet discovered in place of his mother, which had found a home next to the inkwell in his study?

Fig. 4.10. Map showing movements of Northern Sector Khmer Rouge

rebels from Ratanakiri to Phnom Penh (January — April 1975)

From Røed-Larsen, P., Spesielle Partikler, p. 650

In the years of conflict that followed, the plantation was used as a refuge for several Khmer Rouge divisions, vagrants, and prisoners of the regime, and then by the Vietnamese troops during their 1979 invasion. Over the course of this period, the grounds were apparently picked clean. Røed-Larsen recounts how, many years later, in 1995, the property was examined by a ministerial housing inspector and the resulting report made no mention of a safe in the basement or any miscellaneous scientific equipment. The property was valued at 290 million riel, or about $75,000, a prohibitive price to anyone but the most elite provincial ministers.

Not surprisingly, given the site’s obscure location and the country’s ongoing economic woes, the property was never redeveloped. The state attempted to seize the plantation on several occasions, but the estate’s legal status remained unresolved, particularly since Raksmey Raksmey de Broglie was never officially located. Many travelers on the Mekong have remarked at the unusual sight of the main house’s grand ruins, just visible from the river, surrounded by rows and rows of overgrown hevea trees. Locals pass along several competing stories about its onetime inhabitants, involving sorcerers, the CIA, and even Pol Pot himself. The name La Seule Vérité has been completely lost to time.

After landing in Phnom Penh in March 1975, Raksmey attended a brief funeral ceremony for his father inside a small wat near the university, as it was no longer possible to travel back through Khmer Rouge territory to the plantation. The Mekong was now mined all the way up to the Laotian border. Days after this, flights out of the country were suspended, and Raksmey was prevented from returning to his lab in Switzerland. He and Tien shared a small flat in the Khan Chamkarmon district of Phnom Penh for a little over a month, waiting, with the rest of the city, for the imminent arrival of the Khmer Rouge. No one knew what this would mean, though many diplomatic organizations, including the U.S. embassy, took no chances and evacuated all of their members.

Finally, on April 15, 1975, trucks and tanks full of battle-weary Khmer Rouge soldiers streamed into the city down Highway 5 and “liberated” Phnom Penh. They were met by a jubilant populace, who hoped that this signaled the end of the endless civil war. Peace could now prosper in a region that had not seen peace in many years. It was not long, however, before Cambodians came to terms with the reality of these liberators. Within days, the entire city — all two million inhabitants — was ordered to leave for the countryside. The Khmer Rouge had begun its surreal war against time.

In pursuit of a total socialist order that eradicated the individual and shunned all Western influence, the Khmer Rouge bombed the national bank and symbolically burned its currency in the streets. They turned the National Library into a horse stable and pig farm, and nearly all of the books — both Khmer and French — were indiscriminately destroyed or used for cooking fires, toilet paper, or rolling cigarettes. Røed-Larsen includes a famous photograph of three young Khmer Rouge cadres standing around a torn-up copy of Dante’s Inferno, smoking cigarettes rolled from its pages, a look of weary amazement in their eyes.

Knowing that religious traditions could pose the most serious threat to their plan to socially engineer the populace, the Khmer Rouge forced the Buddhist monkhood, the spiritual backbone of Khmer society, to disband. Their sutras were seized and burned; their wats were turned into granaries or fish sauce factories, the altars pushed aside to make room for great barrels of fermenting anchovies. The Khmer Rouge leadership wisely co-opted several familiar Buddhist notions — such as selflessness and transcendence — for use in their extreme form of Marxist ideology, with spiritual nirvana replaced by the perfect embodiment of the state, Angkar.

Yet monks were by no means the only targets of the Khmer Rouge. Intellectuals, academics, artists — anyone with a perceived connection to the West, including those spotted simply wearing spectacles — were all rounded up, tortured, and, in most cases, summarily executed. Eventually, in a sign that the system was rotting from within, the paranoid Khmer Rouge leadership began to turn on their own ranks, arresting hundreds of Khmer Rouge cadres suspected of being traitors to the Angkar cause. Those who did the arresting were then arrested, and so on.

Røed-Larsen wonders (656) why, given their disdain for historical transcripts, the Khmer Rouge kept such comprehensive records at the Tuol Sleng, or “S-21,” security prison, a former Phnom Penh high school that had been converted into a torture camp. The place was run with astonishing efficiency by Comrade Duch, a former mathematician. Perhaps sensing the chasm left by the erasure of the written word, Comrade Duch began to forge a new history, a new kind of truth.

The S-21 documentation division, including a young photographer named Nhem En, meticulously recorded every arrival to the camp. Following strict orders, Nhem En would remove the new prisoner’s blindfold and then take a series of photos: facing the camera, in profile, occasionally from the back. After a prominent prisoner died of torture, he would also take postmortem photos, the pools of blood like black ink against the white cement floors. Nhem En faced immediate execution if the photos were not up to Comrade Duch’s exacting standards. He thus took great care with the lighting, the placement of the prisoner in the frame, the shallow depth of field. His art kept him alive, but it also became something alive itself.

Читать дальше