Despite Raksmey’s social high-wire act, there were two circumstances beyond his control that would later lead to catastrophe. The first was that, unbeknownst to him, Tor Bjerknes had wired a telegraph key into the Khmer Rouge radio tower. This was to beam out the somewhat superfluous and altogether harmless signal “What hath God wrought?” on an obscure frequency. Transmitting this echo of Morse’s first telegram in 1844 was a practice that Kirkenesferda had maintained before each of their bevegelser, or movements, to date. However innocuous the signal, permission was not requested from their hosts, and Raksmey had no knowledge of the wiring or the transmission.

Second, and perhaps more serious, was the coincidental and unannounced visit of Pol Pot himself to the camp, a visit that, due to security concerns, not even Khieu Samphan had been made aware of. Pot normally lived two hundred kilometers to the south, in the Cardamom Mountains, in a top-secret Khmer Rouge compound called Office 131. He presumably had made the risky and arduous trip to 808 in order to discuss political strategy with Samphan and Sary face-to-face. Pol Pot must have been surprised to see that in his absence, a theater troupe had been invited to perform at the camp, but we cannot know his initial response, since prior to the show there was no witnessed confrontation between Pol Pot and Samphan.

The great irony is that Kirkenesferda — as they would do for their bevegelse in Sarajevo sixteen years later — had theatrically “reserved” certain seats in the audience for the major political players in the current conflict. There was a seat set aside for former U.S. president Richard Nixon; for Prince Norodom Sihanouk; for Chairman Mao Zedong and Vietnamese prime minister Ho Chi Minh, both already deceased; for Thailand’s acting prime minister, General Kriangsak Chomanan; for Hun Sen, the Vietnamese-installed head of state in Cambodia; and for Pol Pot. These were meant to be symbolic, a kind of “meta-material extension of the stage” (718), as Røed-Larsen terms it, but just before the curtain went up, the real Pol Pot emerged from a building and took the seat reserved for him, causing a stir in the audience, which also was unaware he was in camp. Raksmey was the only one who saw what had happened. It would only be after the show that the troupe’s other members discovered that Pol Pot was in attendance.

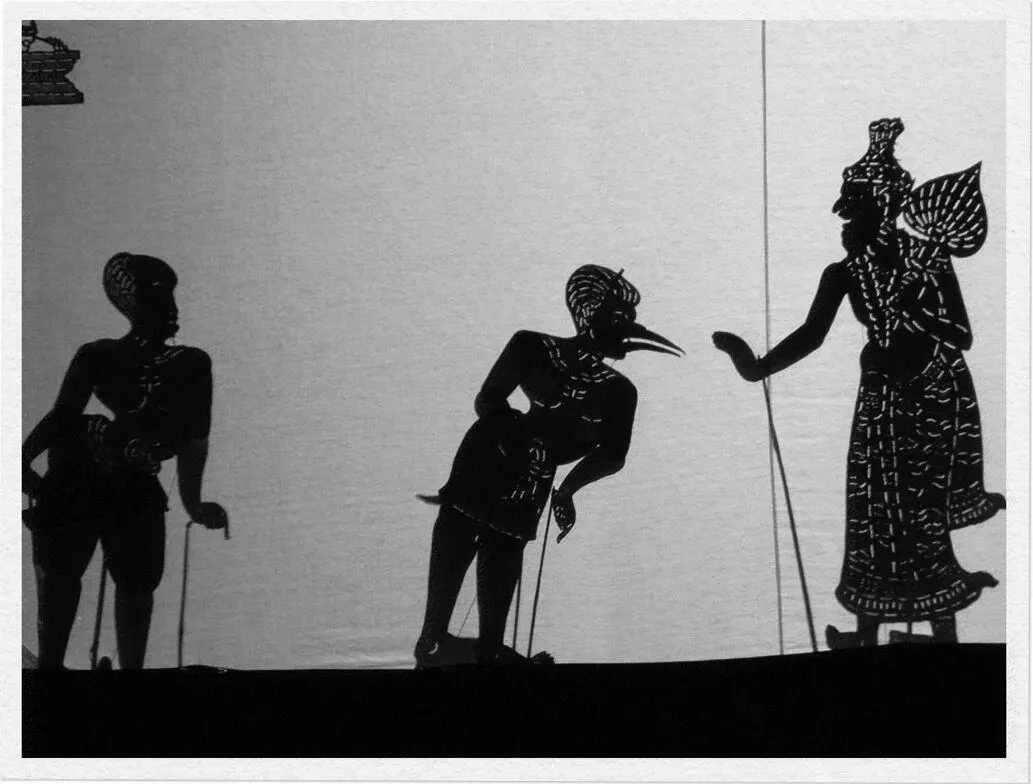

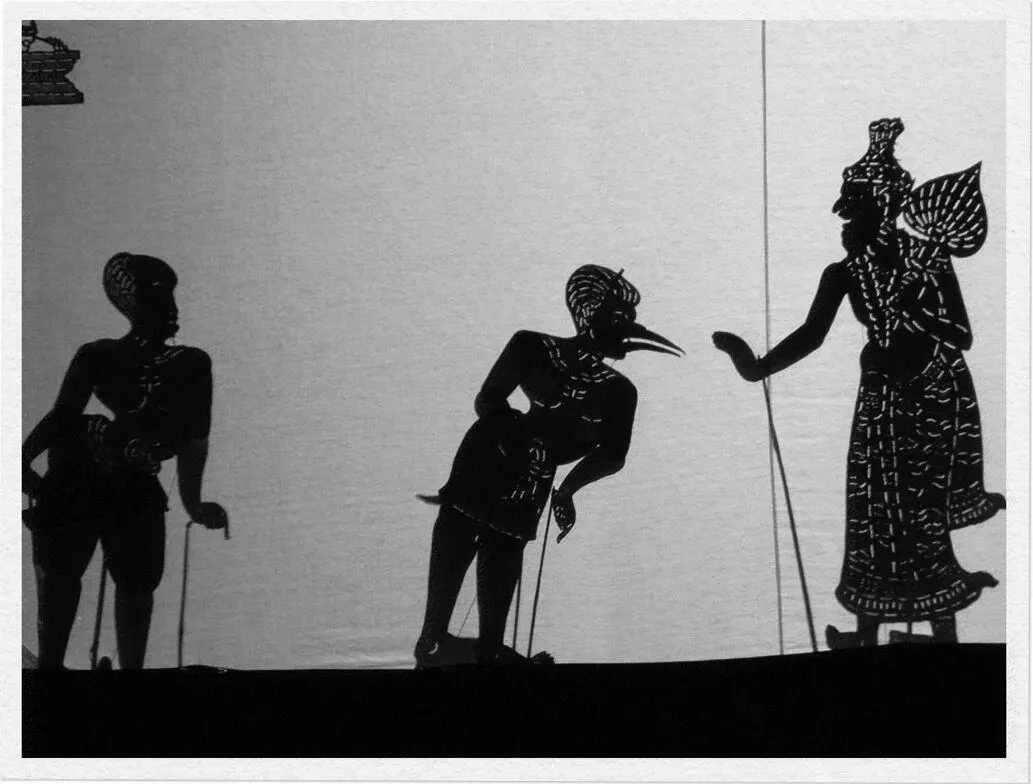

What happened next is covered in some detail by Røed-Larsen, who, as always, takes great pains to document every second of each of Kirkenesferda’s bevegelser. Kirkenesferda Tre was to be the troupe’s most complex creation to date, though the show would start ordinarily enough. When the curtain opened, traditional Khmer shadow puppets made from tanned buffalo hide appeared against a white screen. A scene from the epic Reamker play unfolded, in which the ten-headed monster Krong Reap, disguised as an old man, kidnaps the beautiful Neang Seda. The Reamker is a Buddhist adaptation of the Hindu Ramayana and a mainstay of Cambodian theater. As was custom, the play was accompanied by a live, but hidden, four-piece Khmer pinpeat band, even though this music had not been heard by many of those present in more than four years. At this point, one cannot help but wonder what the audience of fallen Khmer Rouge elites were thinking: here was a traditional Khmer art form, part of a rich cultural heritage that they had attempted to eradicate during their time in power, now being enacted for them. The play itself was amusing—“the hijinks of disguise [is a] universal wellspring of humor” (722) — and apparently soldiers were laughing at the antics of Krong Reap trying to behave like an old man.

Fig. 4.13. Traditional Khmer Lkhaon Nang Sbek, featuring a scene from the Reamker epic.

From Cohen, M., “Khmer Shadow Theatre,” p. 187

If this puppetry was vaguely confrontational in its very reenactment, this was by far the least controversial aspect of the show. The piece quickly veered off the rails: in the middle of the scene, metallic bird rod puppets came down from above and began to attack Krong Reap and Neang Seda, ripping off pieces of their arms and legs and gathering them into a nest. The birds sported antennae made from television radials, beautifully latticed rice paper wings, and flowing tails of magnetic cassette tape and pocket-watch gears, and they wielded “abnormally long and crooked beaks cut from shellac records and whalebone” (735). The Khmer shadow puppets, or what was left of them, fled the stage.

For those familiar with the Reamker epic, the performance of which could often stretch to twelve hours, this aerial attack by apocalyptic Frankenstein birds was an affront to the very form of Lkhaon Nang Sbek. Before the Khmer Rouge came to power, the Reamker was performed by a wide range of puppeteers, actors, and dancers, from regional groups on up to the Royal Cambodian Ballet. While each performer was allowed a certain personal flourish, it was also critical that they stayed within a strict, familiar framework. Every Cambodian knew the story by heart, so it was not uncommon for audience members to leave and return over the course of the day, instantly recognizing where they were in the story. Thus, the manner of Kirkenesferda’s narrative disruption was deeply forbidden. The group had painstakingly honored the form with their meticulous reenactment, only to completely disregard it with their experimental blitzkrieg.

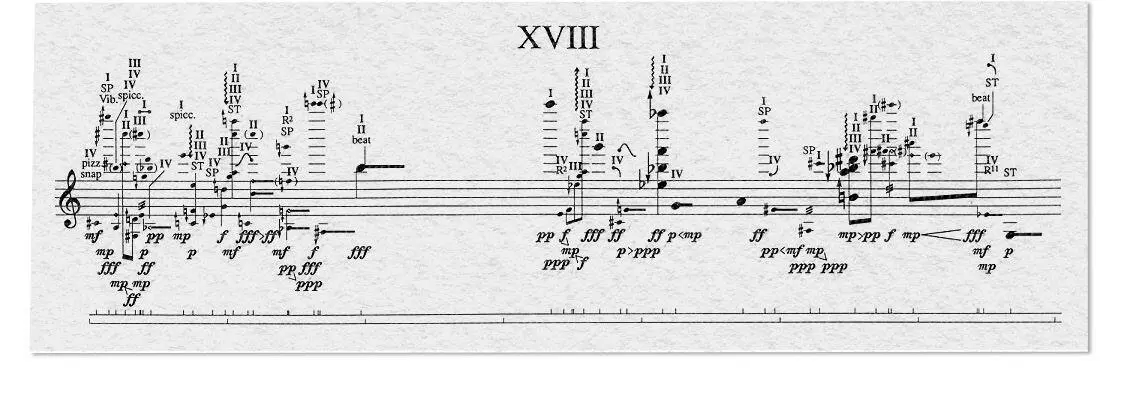

Soon the birds returned with more items for their nest: tiny musical instruments, presumably taken from the pinpeat band, who had begun to stop playing one by one as the birds stole their instruments, until only a fiddle remained. Left alone, the fiddle started to play wild, chaotic strokes — an excerpt from John Cage’s Freeman Etudes .

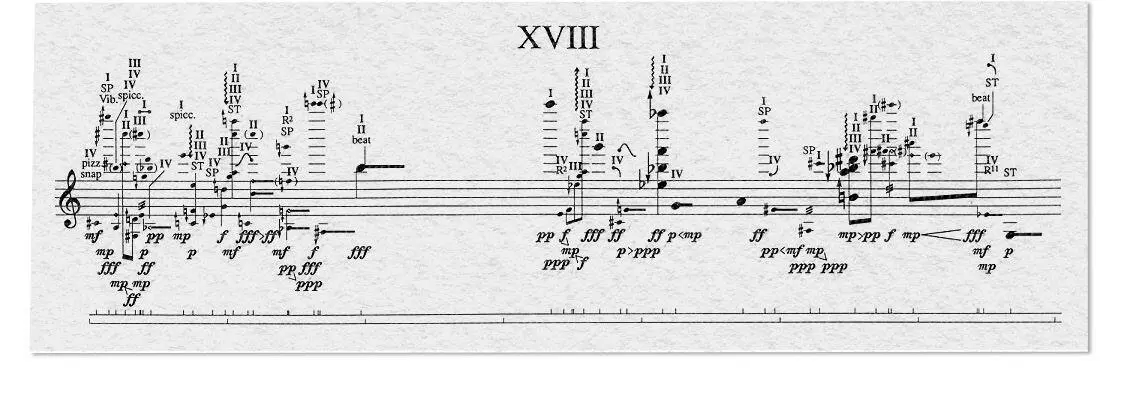

Fig. 4.14. Notations from “Freeman Etude #18,” by John Cage

From Røed-Larsen, P., Spesielle Partikler, p. 749

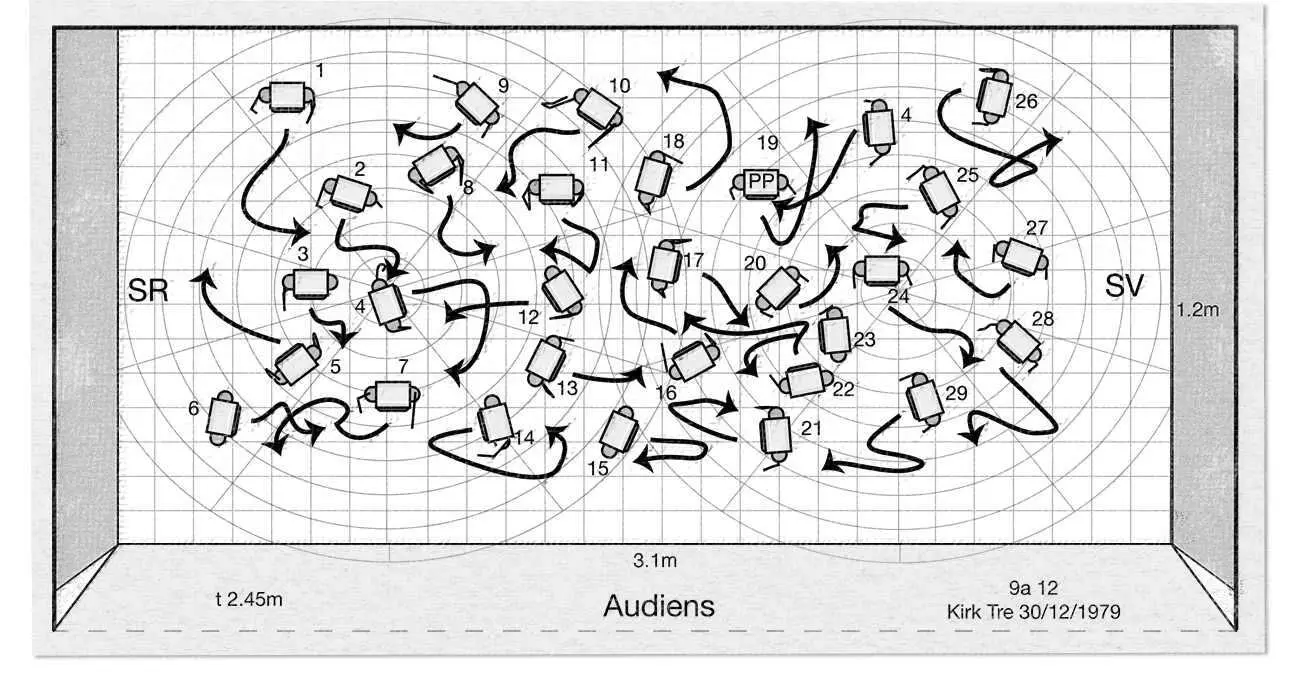

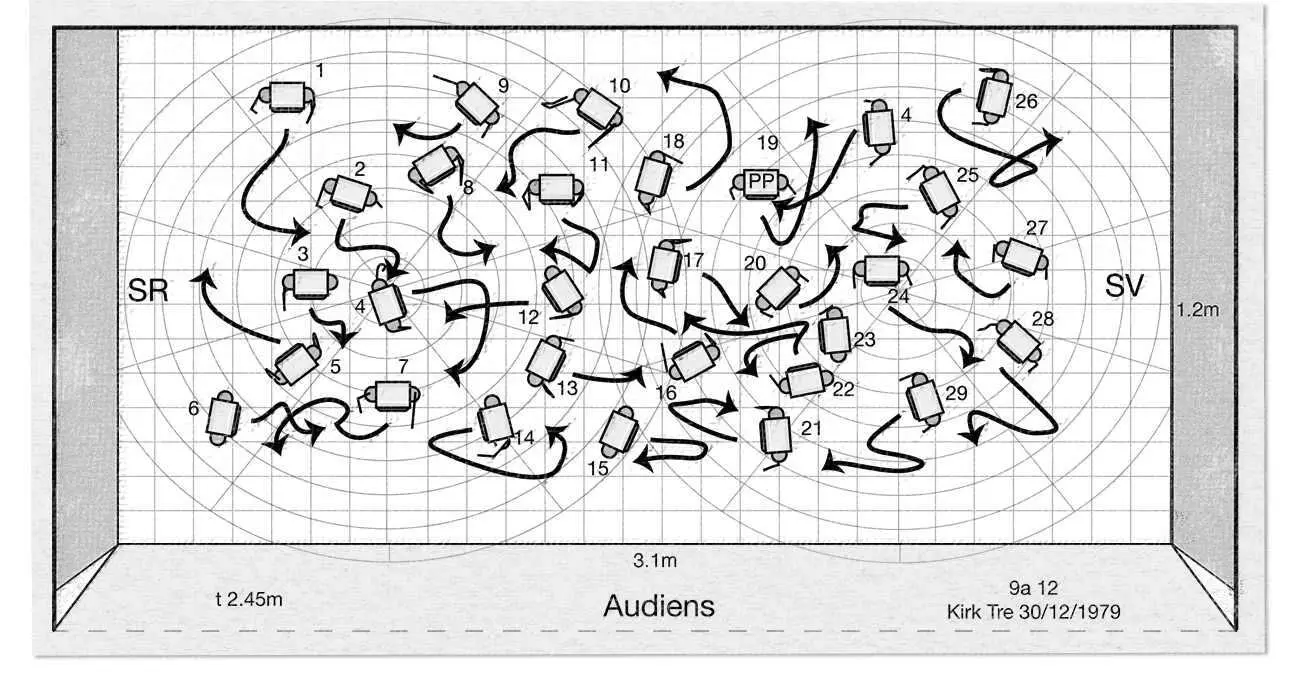

The birds brought still more things to the nest: numbers, pieces of mathematical equations, Greek symbols. When the nest had grown to tremendous proportions, it began to tremble and then exploded, sending the birds flying offstage. The fiddle music ceased. The stage went black except for a single red spotlight. A mist appeared, and then puppet figures, dressed in those same familiar black outfits of the Khmer Rouge, began to move around the stage, their faces masked by krama scarves. One by one, these scarves came off, revealing tiny television screens instead of faces. Each screen showed the curiously gentle visage of Pol Pot, smiling, nodding, on a loop. There were two dozen, then three dozen Pol Pot figurines wandering around the stage, smiling, nodding to one another.

Each of these puppets, designed by Kermin Radmanovic and Tor Bjerknes, was an astonishing work of art — the inner mechanics of their one-off design were complex beyond belief. But while exceedingly intricate, each puppet had also been carefully designed to withstand the rigorous environment of the humid jungle, for a single short circuit would have ruined the entire choreography of the show.

Fig. 4.15. Figure of Sequence 9a, 12: “Intermingling puppets, cascading, choreographed Brownian motion.”

Читать дальше