Father Pennant stood in one spot all parade long. So, he was not aware of any incidents that took place in other parts of town. He heard about some of them in the bits of conversation he caught from those who passed by. For instance, he heard about two or three drunks, the most unruly of whom seemed to be George Bigland.

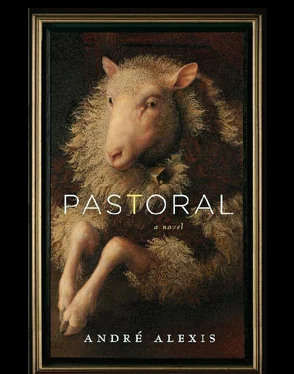

— Only thing he ever does is drink and fuck sheep, said someone.

— Yeah, it’s a vicious circle, answered someone else.

Also, Esther Greenwood, whom Father Pennant knew as soft-spoken and modest, had exposed her breasts, as she had been doing for years in an effort to bring attention to the various cancers that afflicted women in Barrow. When Esther had first decided to bare her breasts, some fifteen years previously, she had indeed brought attention to herself and her cause. But times had changed. Few people paid attention to her, and the police, one of whom inevitably brought a sweater to the parade, covered Ms. Greenwood up as soon as she disrobed. Over the years, other women had bared their breasts in sorority with Esther, but not this year.

Two hours after the parade had begun it ended. People dispersed. Those who were incapacitated were helped away. And for a moment Father Pennant saw the town cleared (or at least clearing) of people. Plastic cups and paper plates moved like little animals across the streets and lawns in the centre of town. As he was walking back to the rectory, the street cleaners came. A small battalion of men with push brooms began to restore order. It struck Father Pennant as an oddly sinister sight.

Just as sinister was the lone man astride the shoulders of Richmond Barrow’s statue. The man seemed to be drunk and, from time to time, called out for what Father Pennant assumed were his friends. That is, he shouted ‘George’ or ‘Johnny’ or ‘Arlene.’ There was no one around him. He had been abandoned. Nor, as far as Father Pennant could tell, did the man want to come down. As the priest passed, the man stopped shouting and was polite.

— How are you, Father? Having a good day? I wish there were more apples, don’t you?

And then, as if he’d recalled something crucial, he began shouting out his names again.

— Arlene! Johnny! George!

It was as if a moment of sanity had passed through a madman, like a shiver animating someone feverish.

Father Pennant did not go to the dinner and dance at the firehall. Lowther had warned him that, the previous year, thirty people had been sent to the hospital by coquilles St.-Jacques that had proved to be a ruthless laxative. Father Pennant and Lowther ate at the rectory.

At eleven, they took up their candles and flashlights and walked to the Petersen gravel pit, met on the way by dozens of festive others. For Father Pennant, this walk in darkness, flashlights guiding their steps, was the most striking part of the day. Yes, some of those who walked were so drunk they had to be helped, but most were buoyed by a spirit that came from somewhere beyond the nameable. It was a kind of pleasing fright, this being out under the star-filled sky, the darkness and mystery only slightly lessened by company.

The gate to the gravel pit had been opened. The sound of laughter and a chaos of light accompanied Father Pennant and Lowther through the trees, around the hills and to the pit. And here there was a marvellous vision: hundreds of people gathered around the water, encircling the gravel pit. And it seemed each of the hundreds held his or her own lighted candle. The candles were tall, short, thin, thick. Some were scented; most were not. So many candles that the night was lit up by flickering flames. The black water in the pit was flecked with candlelight, the whole surface looking like a plane of anthracite on whose edges hundreds of fireflies had settled. It was one of the most beautiful things Father Pennant had ever seen.

Then, just before midnight, there was a commotion as Mayor Fox made his way to the edge of the pit. The townspeople began to sing, quietly at first but then with confidence. They sang a hymn whose melody Father Pennant did not recognize but whose words he knew well.

— The Lord is my shepherd; I shall not want …

When the hymn was finished, Mayor Fox, speaking through a bullhorn, thanked everyone for coming. He spoke about how bountiful the preceding year had been. He promised the coming year would be just as good. He said the names of those who’d died during the previous year. Then, asking for quiet, he put aside his bullhorn and began to speak his necessary gibberish.

— Uine iat eooe iut xosl oox naz iu setu …

The crowd was now so quiet one could hear the flippety-flip of candle flames bending and rising in the wind. Mayor Fox stepped off the shore and into the black water. Most momentarily held their breath. The only sound, save for the wind and candle flames and the splash of water, was the voice of Mayor Fox reciting his nonsense as he walked in broken rhythm across the top of the gravel pit. Only when he had made it from one side to the other was there a collective sigh and then a great cheer. Mayor Fox had succeeded and his success was theirs. Joy spread through the crowd in waves, like a communal, prickly blush. And for a moment, there was harmony. And then, one by one at first, the crowd extinguished its candles. Flashlights were turned on and slowly the people of Barrow walked back to town together.

Despite himself, Father Pennant was unnerved by Mayor Fox’s walk across the pit. As he went home, the day returned to him in all its uncanny aspects: from the sweet red skulls to the fireflies on anthracite, from the face in the insect to the drunk on Richmond Barrow’s back. It occurred to him that Barrow itself was neither good nor evil but was, instead, animated by whatever it was that animated the land, the thing that animated each and every one of them and, so, revealed itself in its hiddenness. In fact, one felt, or he felt as he walked — blasphemous though the thought was — that God was only an aspect of the hidden, an idea brought into being by man in order to point to a deeper thing that had no name and reigned beyond silence.

For an instant as he walked from Petersen’s gravel pit to St. Mary’s rectory, Christopher Pennant was vertiginously pagan and in touch with the hiddenness that coursed through him and his God.

Naturally, he kept these thoughts and feelings to himself.

IV — JULY, AUGUST AND AFTER

Jane had spent Barrow Day alone, for the most part. She’d watched the revellers from inside her parents’ house, ashamed of what she took to be the town’s puerile ways. Barrow Day was an embarrassment and for a number of years now she had taken to spending June 15th at home, usually alone, usually with a book.

This year, she read Breakfast at Tiffany’s for the fourth time and dreamed of New York and London, Paris and Amsterdam. She almost always enjoyed her solitude, but this year it was charged with something. Something was on its way. Something or someone would come into her life to save her from the louts and boors of Barrow. She could feel it. She sat in the living room, in a chair that had been made by her great-grandfather, the floor lamp with its floral shade beside her, the house smelling of Barrow bread, the noise of the world dimmed by closed doors and shut windows. She left the curtains open, however, and from time to time she could see groups of revellers as they passed.

Robbie had refused to walk naked into Atkinson’s.

After the fire-hall dinner and dance, Jane’s parents returned. They were childishly happy about something. Mrs. Keynes, one of their neighbours, had inhaled an olive pit and had needed the Heimlich to clear her windpipe. That wasn’t the amusing part. What was amusing was the sight of Mr. Chester, a man thin as a whippet and half Dora Keynes’s size, trying desperately to squeeze Dora’s ‘thorax’ (her mother’s word). The definition of futility. Mrs. Keynes had flung him around from side to side in her struggles for breath, until Jane’s father snuck up behind her and, with poor Mr. Chester between them, squeezed the olive out of the exhausted woman.

Читать дальше