Source: Reproduced with permission of Dr Gregory Lisciandro, Hill Country Veterinary Specialists and FASTVet.com, Spicewood, TX.

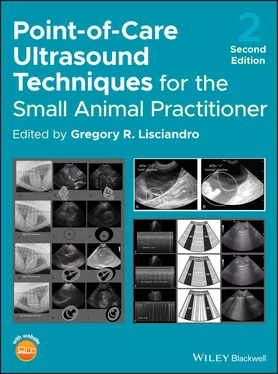

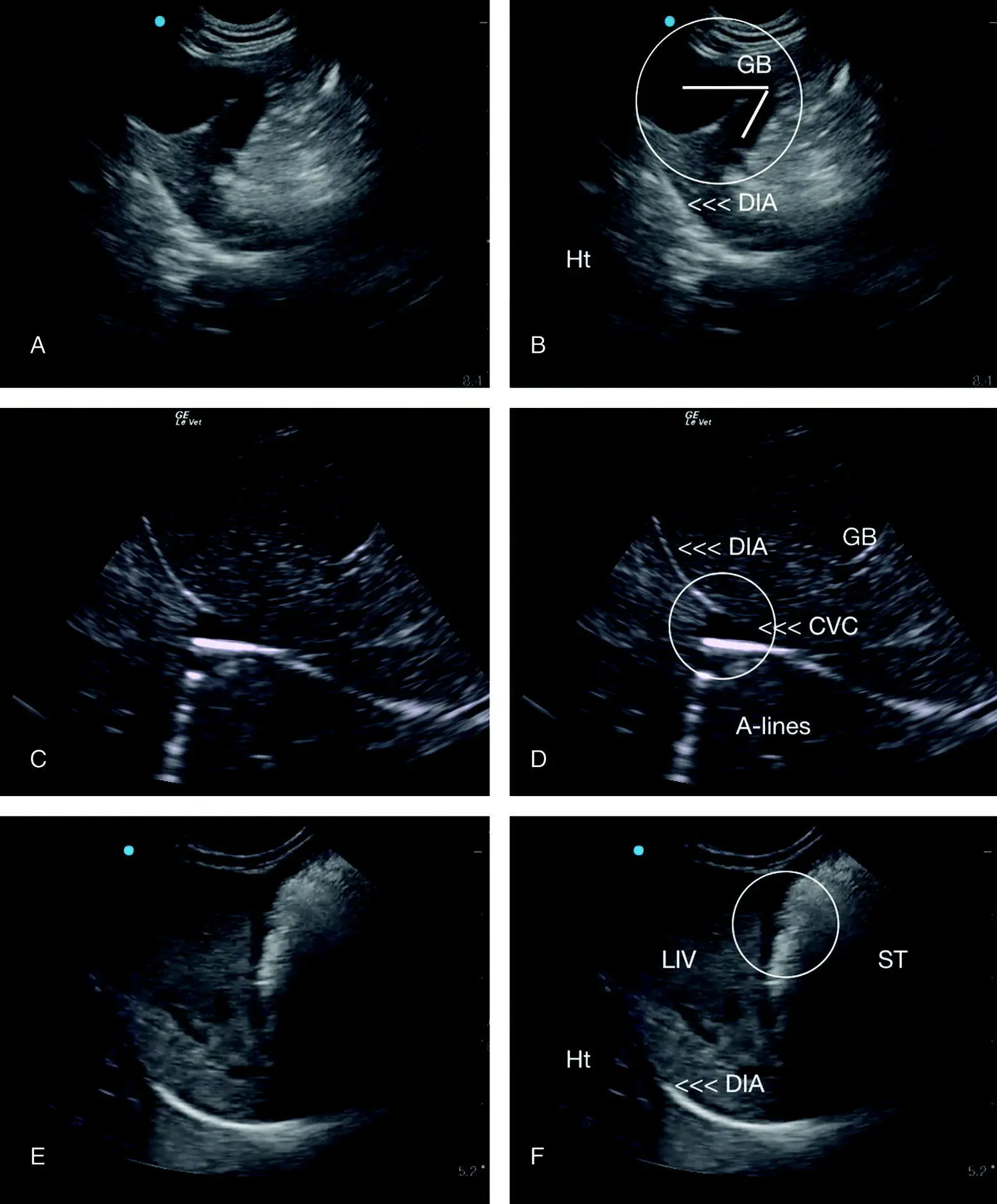

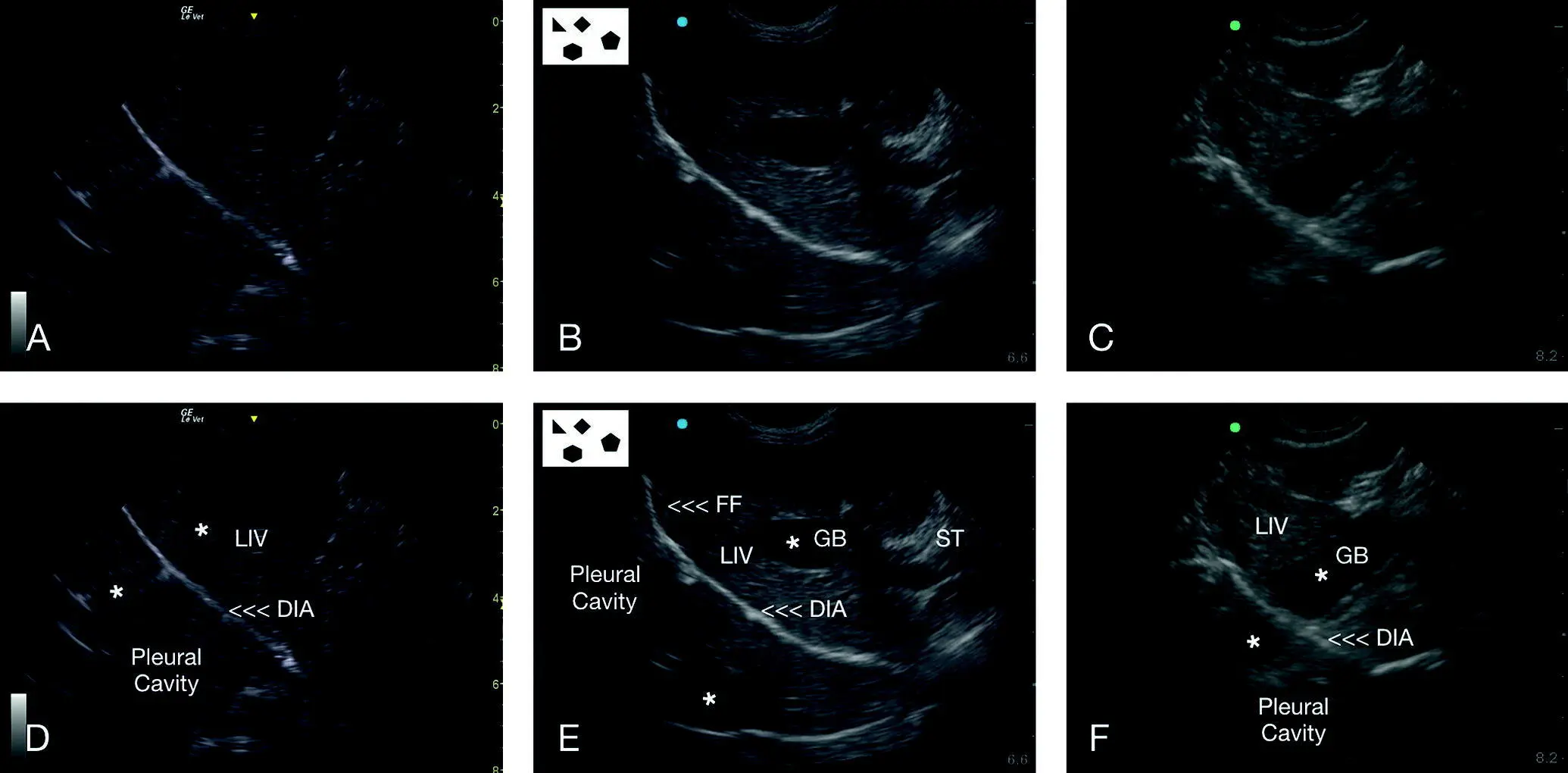

Figure 6.13. Mirror image artifact at the DH view. Mirror image artifact occurs wherever there is a strong soft tissue–air interface and should always be considered at the DH view. In (A) is the same image as in (D) unlabeled and labeled, respectively. The asterisks (*) show the mirroring of the liver on the other side of the diaphragm, falsely making it appear that liver is in the pleural cavity. The gallbladder is not present. In (B) is the same image as in (E) unlabeled and labeled, respectively. The asterisks (*) show the mirroring of the liver and gallbladder on the other side of the diaphragm, falsely making them appear in the pleural cavity. The mirrored gallbladder being fluid filled may be mistaken for pleural and pericardial effusion. The hepatic venous system also may be mirrored into the pleural cavity. In (C) and (F) are the last comparative images showing how the gallbladder may be partially mirrored into the pleural cavity. The question must always be asked – could I be mistaking artifact for pathology? To increase probability for a correct diagnosis, adhere to the described tenets for an accurate diagnosis of pleural and pericardial effusion (see Chapters 7, 18and 21). Note how consistent the diaphragm is within the images as a landmark for proper DH View image acquisition. DIA, diaphragm; FF, free fluid; GB, gallbladder; LIV, liver; ST, stomach.

Source: Reproduced with permission of Dr Gregory Lisciandro, Hill Country Veterinary Specialists and FASTVet.com, Spicewood, TX.

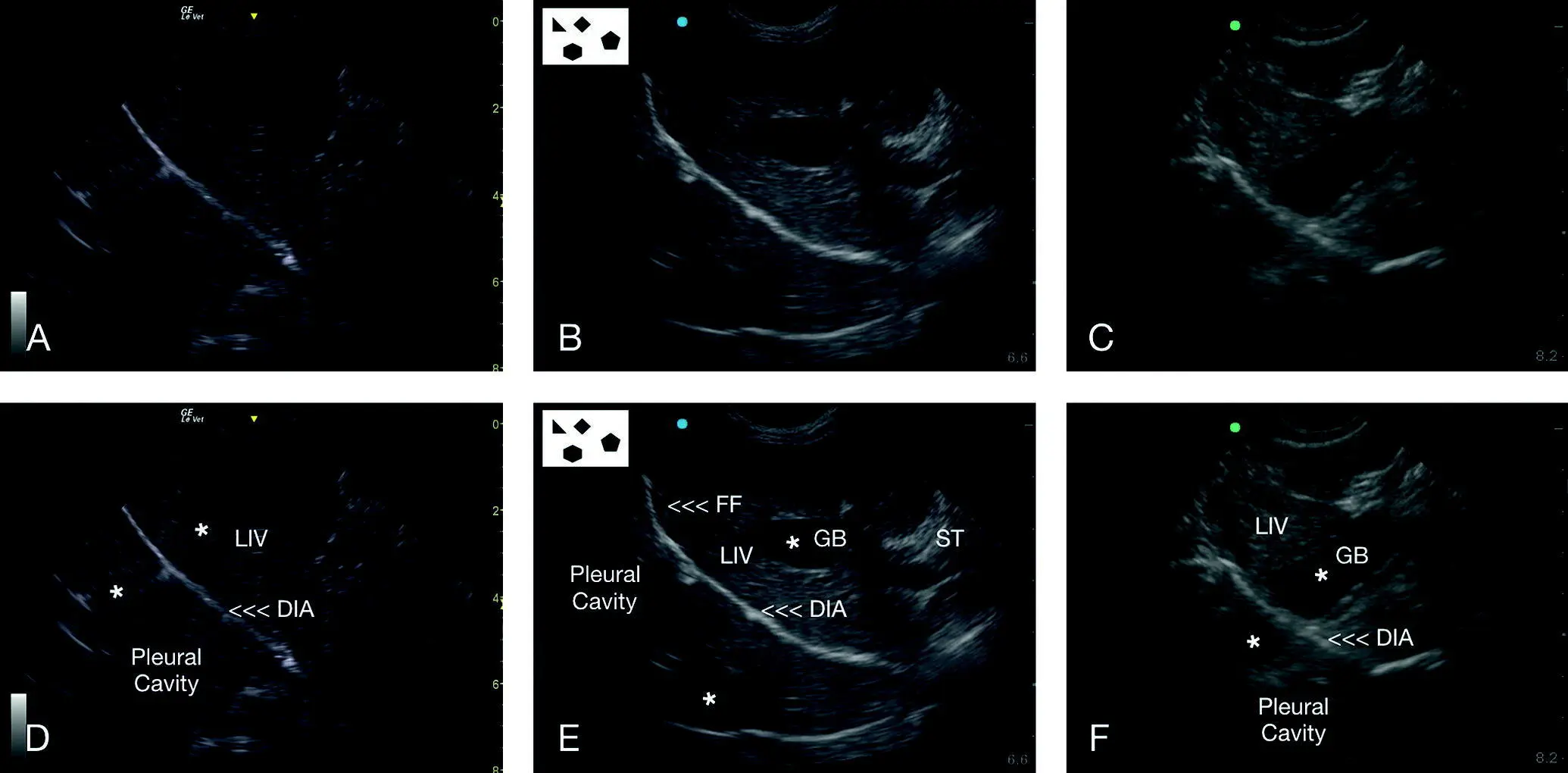

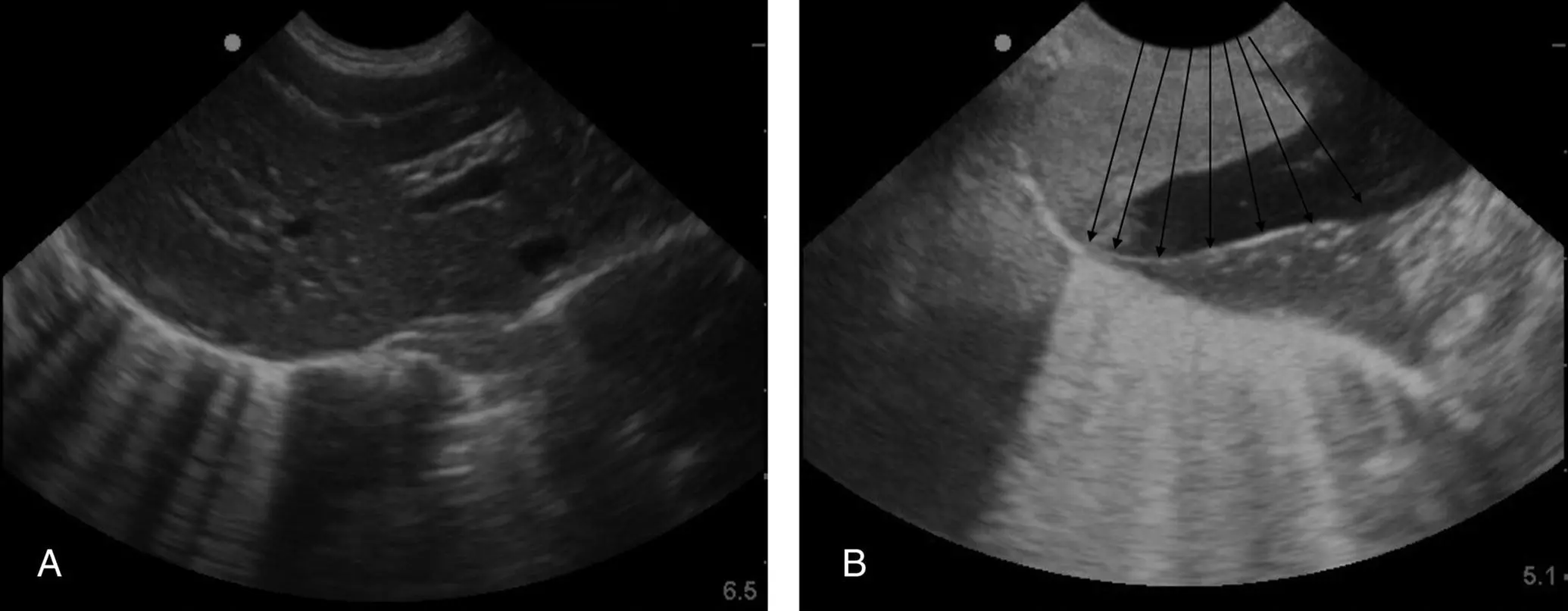

Figure 6.14. Showing B‐lines along the pulmonary‐diaphragmatic interface. Acoustic enhancement requires a fluid‐filled structure, in this case at the DH view the gallbladder. In (A) multiple B‐lines are obvious along the pulmonary‐diaphragmatic interface. In (B) an even greater number almost coalesce along the pulmonary‐diaphragmatic interface. However, and interestingly, they are in the path of the beam (its echoes) and indicated by the overlain black faint arrows on the image made more evident by acoustic enhancement artifact. Note that they are not evident to the left of the image where there is sediment and soft tissue of the liver (versus a fluid‐filled gallbladder). Numbers of B‐lines indicate degrees of alveolar‐interstitial edema and need to be placed in clinical context with a complete Vet BLUE examination (see Chapters 22and 23).

Source: Reproduced with permission of Dr Gregory Lisciandro, Hill Country Veterinary Specialists and FASTVet.com, Spicewood, TX.

Pearl:B‐lines that are evident within the path of acoustic enhancement in the far‐field past the gallbladder should be considered abnormal until proven otherwise and placed into clinical context unless 1–2 are seen in a giant breed. Dry lung should remain dry despite acoustic enhancement (see Figure 6.14).

Edge Shadowing, Side‐lobe, and Slice‐thickness Artifact

These artifacts result in loss of interpretive clarity by the ultrasound machine along any luminal borders, in this case the gallbladder, thus, falsely making the gallbladder appear to contain sediment, other intraluminal abnormalities, or a mass, as well as defects along its wall similar to the urinary bladder (see Figure 6.26) (see Chapters 3and 5).

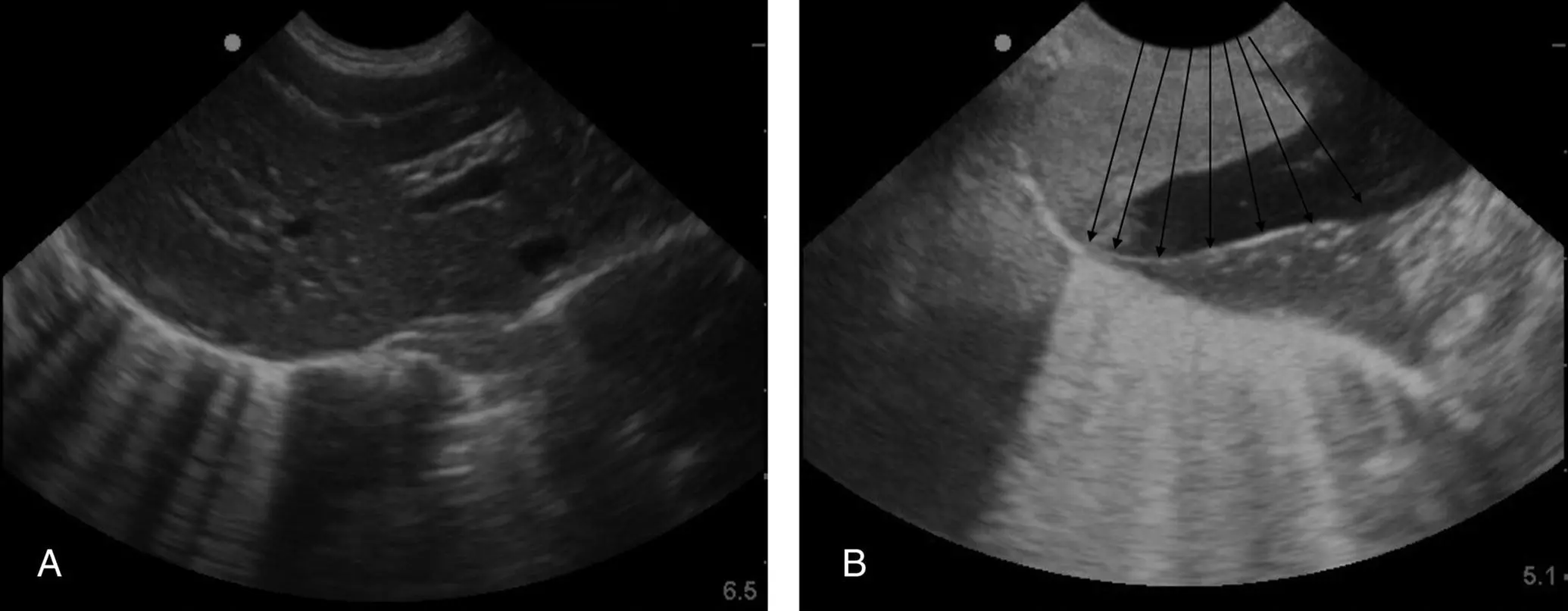

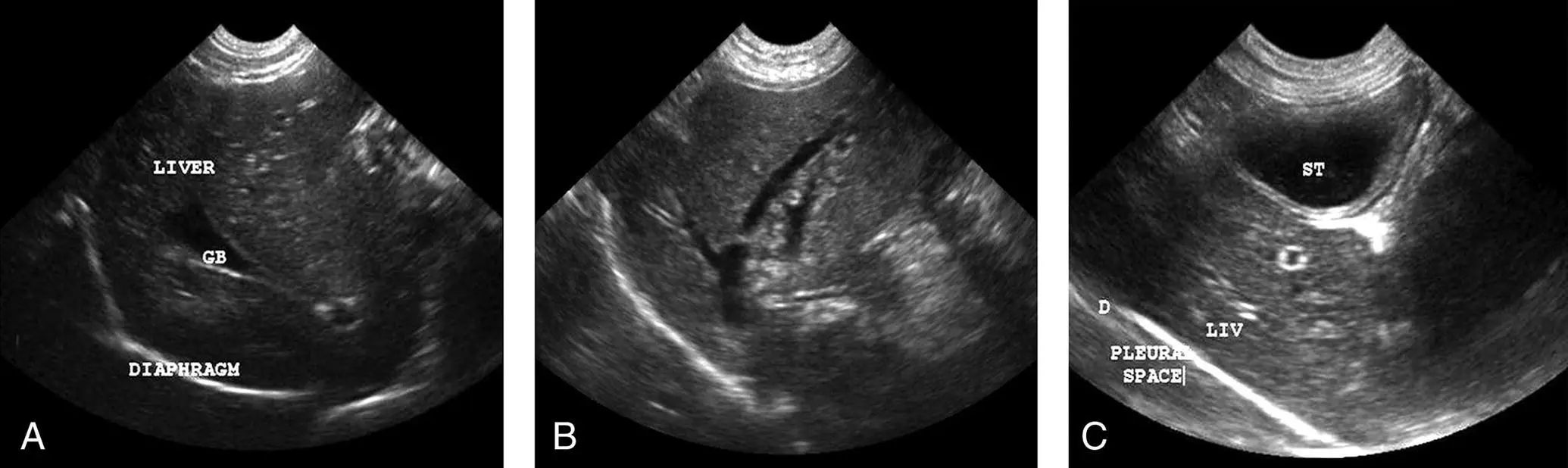

Figure 6.15. Pitfalls at the DH view related to the gallbladder, hepatic venous system, and stomach wall. In (A) the gallbladder (GB) appears triangulated, mimicking free fluid, but by fanning through the gallbladder in both directions, this mistake is less likely to occur. Moreover, free fluid does not have hyperechoic borders as the wall of the gallbladder does. In (B) branching of the hepatic venous system mimics free fluid. In real time and through repetition, the sonographer will get used to where fluid typically pools as well as incorporating the added information of performing the entire AFAST. In (C) the stomach is fluid filled in this patient and can mimic the gallbladder to the hasty sonographer; and its sonographically layered wall can mimic gallbladder wall edema. This area should be avoided by rocking the probe more cranial as shown in the many DH views within this chapter and Figure 5.10. GB, gallbladder; LIV, liver; ST, stomach.

Source: Reproduced with permission of Dr Gregory Lisciandro, Hill Country Veterinary Specialists and FASTVet.com, Spicewood, TX.

Pitfalls Creating False Positives

There are several fluid‐filled or fluid‐associated structures within the liver that the sonographer must be aware of.

Gallbladder and Biliary System

When imaged in certain planes, the gallbladder and common bile duct can appear as anechoic sharp angulations like free fluid. This pitfall, misinterpreted as a false positive, is easily avoided by fanning, tracing, and connecting the gallbladder to its biliary tree ( Figures 6.15and 6.16).

The liver's venous system can appear as anechoic sharp triangulations like free fluid. The venous system as a general rule is not obvious in normalcy when patients are examined in lateral, sternal and standing positions. This false positive is easily avoided because most free fluid is not as linear as the venous system, and the venous system in most instances can be traced and seen branching (see Figure 6.12) (see Chapter 8). Color flow Doppler may be used to distinguish the venous system from free fluid but is rarely needed. Hepatic veins are differentiated from portal veins in a couple of ways. First, portal veins have brighter, more echogenic (hyperechoic) walls when compared to hepatic veins and thus portal veins often appear as hyperechoic (bright white) equal [=] signs (see Chapters 8and 39). Hepatic veins are darker walled sonographically and are generally traced as they drain into the CVC, especially when there is hepatic venous distension (see Figure 6.12F and Chapters 7, 20, and 36).

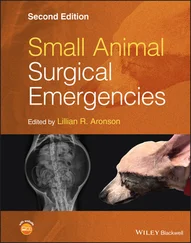

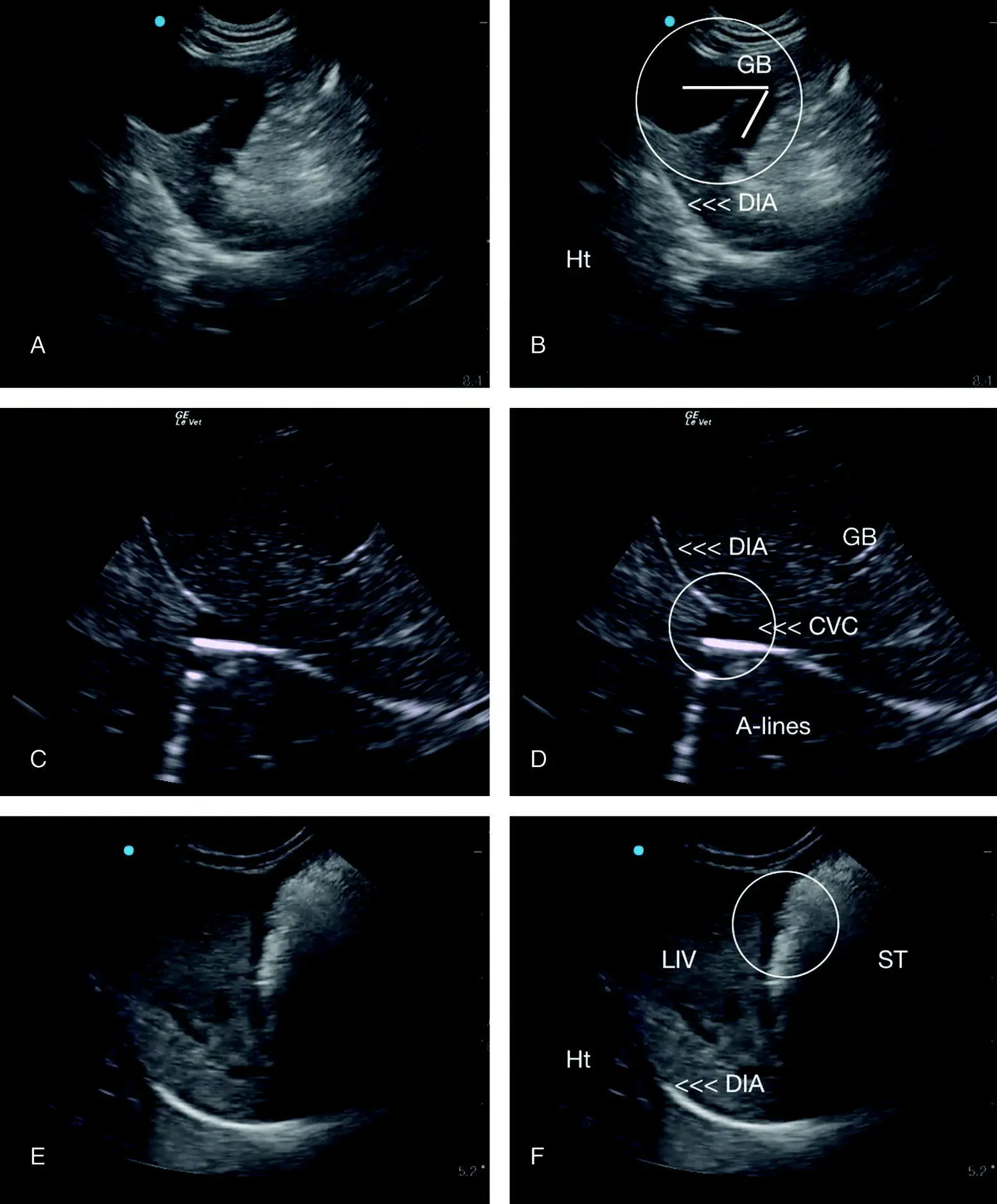

Figure 6.16. Additional examples of pitfalls at the DH view. (A) and (B) are the same image unlabeled and labeled. The gallbladder is bilobed, most commonly seen in cats. It appears similar to free fluid but through interrogation by fanning through the gallbladder in both directions, the rounding of the hyperechoic gallbladder wall differentiates it from free fluid. (C) and (D) are the same image unlabeled and labeled. Note the caudal vena cava (CVC) can mimic pleural effusion at the level of the diaphragm; however, the dynamic changes in CVC diameter with respiratory and cardiac cycles and its A‐lines through the far‐field differentiate the CVC from pleural effusion. In (E) and (F), the same image is unlabeled and labeled with a circle indicating the stomach wall that is anechoic and can mimic free fluid (and its associated edge shadowing artifact; see Figure 3.2). Note how consistent the diaphragm is within the images serving as a landmark for proper DH view image acquisition, which in and of itself (the proportionality shown) will prevent many DH view pitfalls. CVC, caudal vena cava; GB, gallbladder; LIV, liver; ST, stomach.

Читать дальше