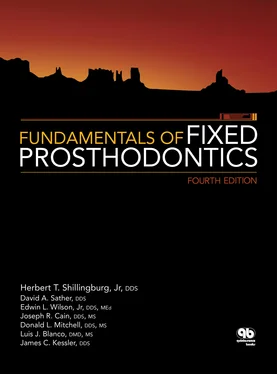

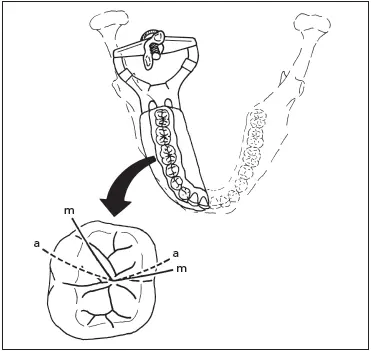

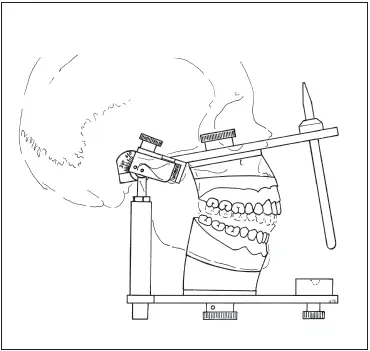

Fig 3-1The articulator should simulate the movements of the mandible.

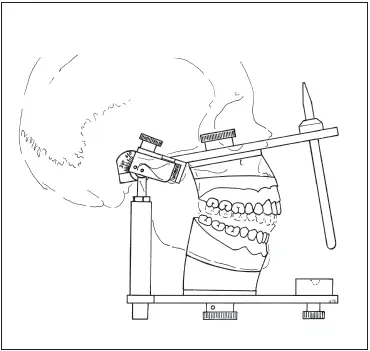

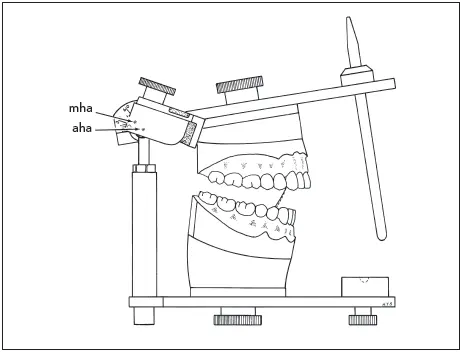

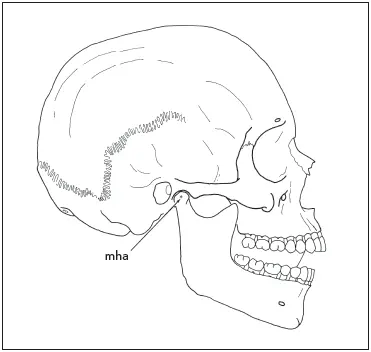

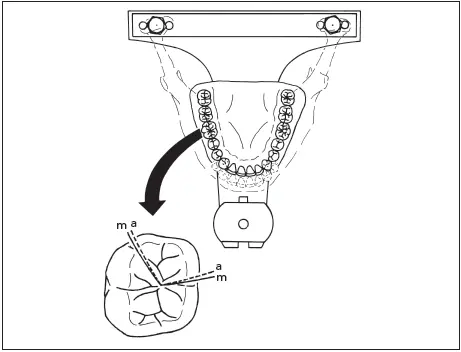

Fig 3-2As the mandible closes around the hinge axis (mha), the cusp tip of each mandibular tooth moves along an arc. (Reprinted from Hobo et al 2with permission.)

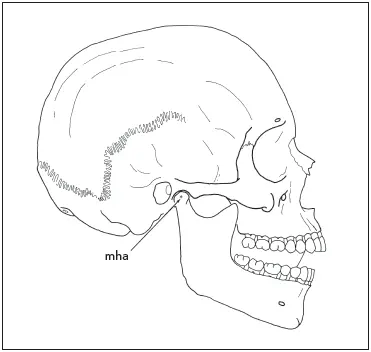

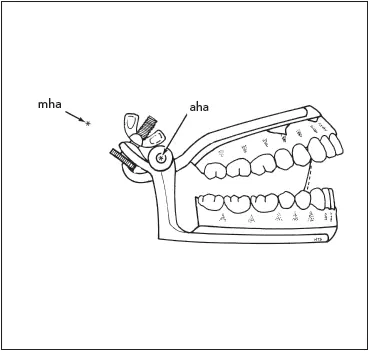

Fig 3-3The large dissimilarity between the hinge axis of the small articulator (aha) and the hinge axis of the mandible (mha) will produce a large discrepancy between the arcs of closure of the articulator (dotted line) and of the mandible (solid line) . (Reprinted from Hobo et al 2with permission.)

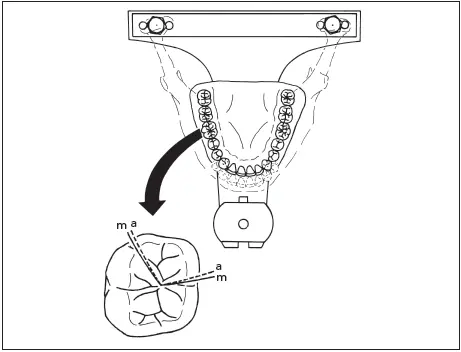

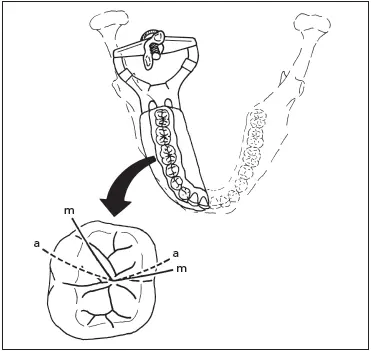

Fig 3-4A major discrepancy exists between the nonworking cusp path on the small articulator (a) and that in the mouth (m). (Reprinted from Hobo et al 2with permission.)

The most accurate instrument is the fully adjustable articulator. It is designed to reproduce the entire character of border movements, including immediate and progressive lateral translation, and the curvature and direction of the condylar inclination. Intercondylar distance is completely adjustable. When a kinematically located hinge axis and an accurate recording of mandibular movement are employed, a highly accurate reproduction of the mandibular movement can be achieved.

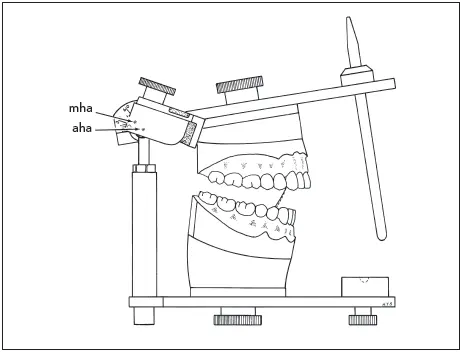

Fig 3-5The dissimilarity between the hinge axis of the full-size semi-adjustable articulator (aha) and the mandibular hinge axis (mha) will cause a slight discrepancy between the arcs of closure of the articulator (dotted line) and of the mandible (solid line) . (Reprinted from Hobo et al 2with permission.)

Fig 3-6There is only a slight difference between cusp paths on a full-size articulator (a) and those in the mouth (m), even though the cast mounting exhibits a slight discrepancy. (Reprinted from Hobo et al 2with permission.)

This type of instrument is expensive. The techniques required for its use demand a high degree of skill and are time-consuming to accomplish. For this reason, fully adjustable articulators are used primarily for extensive treatment requiring the reconstruction of an entire occlusion.

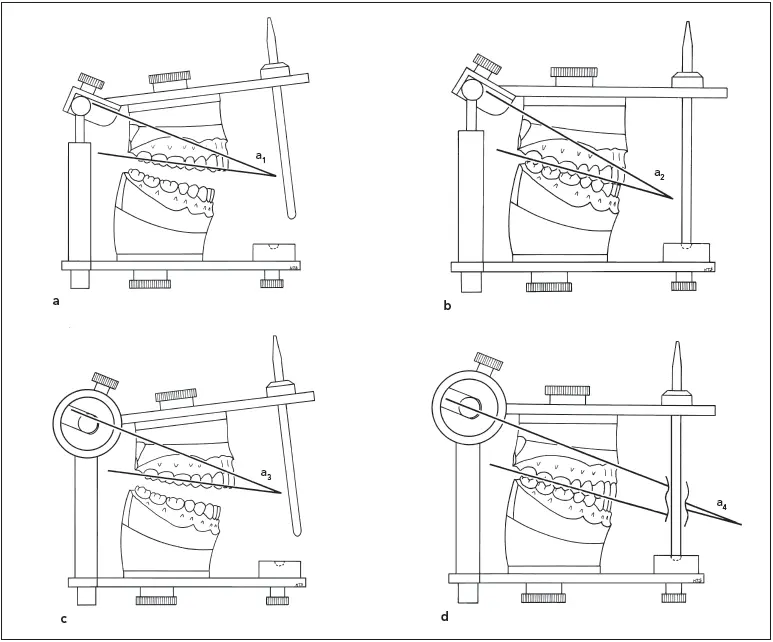

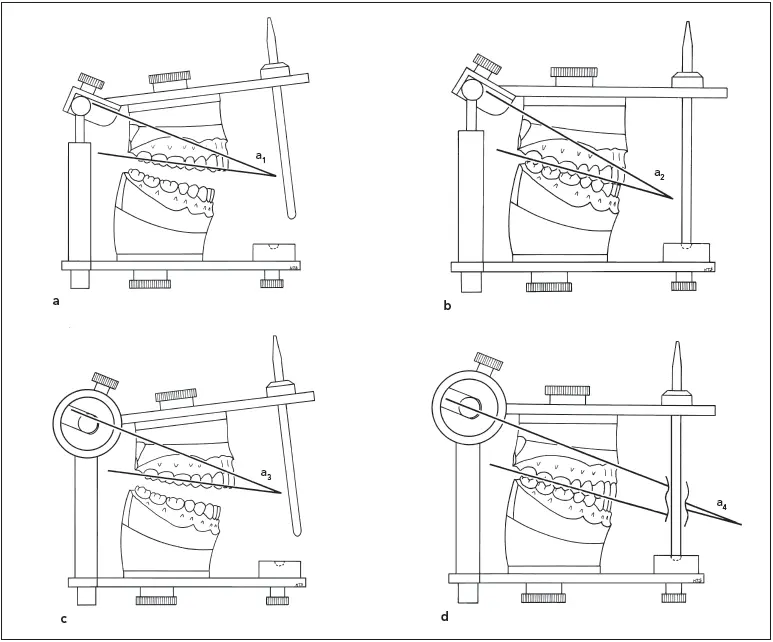

Fig 3-7The angle between the condylar inclination and the occlusal plane of the maxillary teeth remains the same in an open (a) and a closed (b) arcon articulator (a 1= a 2). However, the angle changes in an open (c) and a closed (d) nonarcon instrument (a 3≠ a 4). For the amount of opening illustrated, there would be a difference of 8 degrees between the condylar inclination at an open position (where the articulator settings are adjusted) and the closed position at which the articulator is used.

Arcon and Nonarcon Articulators

There are two basic designs used in the fabrication of articulators: arcon and nonarcon. On an arcon articulator, the condylar elements are placed on the lower member of the articulator, just as the condyles are located on the mandible. The mechanical fossae are placed on the upper member of the articulator, simulating the position of the glenoid fossae in the skull. In the case of the nonarcon articulator, the condylar paths simulating the glenoid fossae are attached to the lower member of the instrument, while the condylar elements are placed on the upper portion of the articulator.

To set the condylar inclinations on a semi-adjustable instrument, wax wafers called interocclusal records are used to transfer the terminal positions of the condyles from the skull to the instrument (see chapter 4 for the technique). These wafers are 3.0 to 5.0 mm thick so that the teeth on the maxillary and mandibular casts are separated by that distance when the condylar inclinations are set.

When the wafers are removed from an arcon articulator and the teeth are closed together, the condylar inclination will remain the same. However, when the teeth are closed on a nonarcon articulator, the inclination changes, becoming less steep ( Fig 3-7). Arcon articulators have become more widely used because of their accuracy and the ease with which they disassemble to facilitate the occlusal waxing required for cast gold restorations. However, this very feature makes them unpopular for arranging denture teeth. The centric position is less easily maintained when the occlusion of all of the posterior teeth is being manipulated. Therefore, the nonarcon instrument has been more popular for the fabrication of dentures. Arcon articulators equipped with firm centric latches that prevent posterior separation will overcome many of these objections.

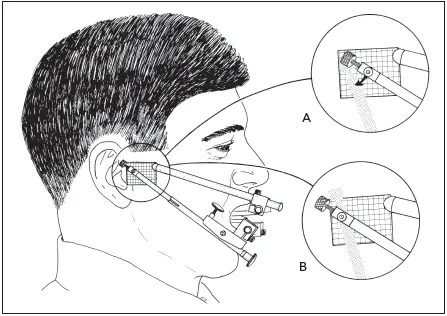

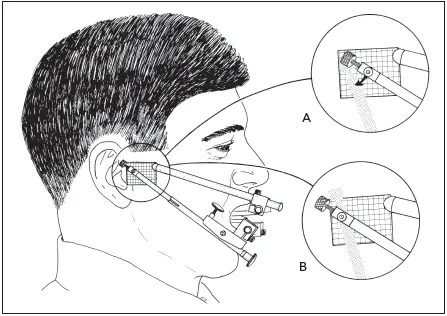

Fig 3-8After the THA locator is placed, the patient is assisted in opening and closing on the THA. An arcing movement of the stylus on the side arm (A) indicates that it is not located over the THA. The side arm is adjusted so the stylus will rotate without moving during opening and closing (B). This indicates that it has been positioned over the THA.

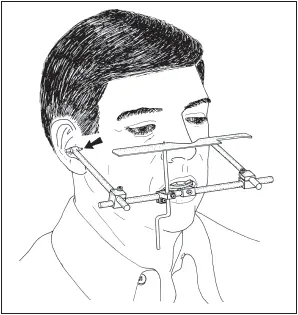

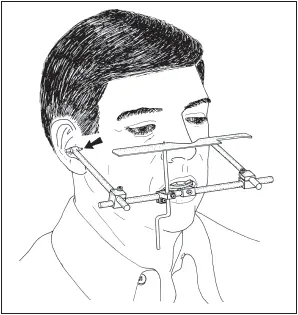

Fig 3-9When a precision facebow transfer is made, both side arms are adjusted so that the stylus at the end of each arm is located over the THA (arrow) . A third reference point, such as the plane indicator shown here, is used.

Tooth–Transverse Horizontal Axis Relationship

To achieve the highest possible degree of accuracy from an articulator, the casts mounted on it should be closing around an axis of rotation that is as close as possible to the THA (hinge) of the patient’s mandible. This axis is an important reference because it is repeatable. It is necessary to transfer the relationship of the maxillary teeth, the THA, and a third reference point from the patient’s skull to the articulating device. This is accomplished with a facebow , an instrument that records those spatial relationships and is then used for the attachment of the maxillary casts to the articulator.

The more precisely located the THA, the more accurate the transfer and the mounting of the casts will be. The most accurate way to determine the hinge axis is by the “trial and error” method developed by McCollum and Stuart in 1921. 5A device with horizontal arms extending to the region of the ears is fixed to the mandibular teeth. A grid is placed under the pin at the end of the arm, just anterior to the tragus of the ear. The mandible is manipulated so that the condyles are in the optimum position in the mandibular fossae with the articular discs properly interposed, from which it is guided to open and close 10 mm. As it does, the pin will trace an arc ( Fig 3-8). The arm is adjusted in small increments to move it up, down, forward, or back, until the pin simply rotates without tracing an arc. This is the location of the hinge axis, which is marked with ink on the patient’s face.

Читать дальше